Rice bran has been shown in recent studies to help reduce inflammation in the digestive tract, but the mechanisms by which it affects the body have yet to be clearly elucidated. Using an SRG award, Kazuki Tanaka (Keio University, 2020 and 2021) isolated individual bacteria with the potential to produce colitis-suppressing substances and hopes to commercialize an anti-inflammatory agent in cooperation with a startup.

* * *

Japanese dishes like sushi and ramen are famous worldwide. And many Japanese foods are known for making us healthier, notable examples being natto (fermented soybeans), miso (fermented soybean paste), and matcha (green tea powder),[1][2][3] which feed our gut’s good bacteria to help us stay in shape.[4] Think of them as helping the water in our inner fish tank stay clean.

Another such food is rice bran[5]—the outer layer of brown rice—which has been shown in recent studies to help reduce inflammation in the colon, which is a part of the large intestine.[6][7][8][9] Rice bran is rich in fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants—nutrients that work like a multivitamin pill[7][8][10][11] to not only nourish the body but also to make our gut happy and potentially reduce inflammation. Science, though, is still trying to figure out exactly how rice bran affects the body.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a debilitating condition characterized by inflammation of parts of the digestive tract. Many of the genes linked to this disease have been identified, yet the number of people getting IBD in Japan has skyrocketed in recent decades.[12] This suggests that the disease is not just about genetics; something else is at play—many scientists believe that an imbalance in the gut’s bacteria population might be a big factor. Using advanced DNA techniques, various studies have tried to pinpoint which bacteria trigger IBD and which ones inhibit it. But understanding the world of bacteria is like solving a giant jigsaw puzzle without knowing what the final picture looks like.[13]

The gut is always changing, and this makes studying it tricky—it is like trying to figure out the story of a movie by only seeing random scenes. Plus, everyone’s gut movie is different because of discrepancies in our diet,[14] lifestyles,[15] and environments.[16] So, to fully understand the many bacterial stories, scientists believe we need a big-picture approach.

Isolating Colitis-Suppressing Bacteria

In my research that was funded in part by SRG, I used a special mouse model to dig deeper into how eating rice bran might affect our gut, particularly whether rice bran might hold the key to keeping inflammation at bay. I adopted a technique that allowed me to look at a lot of data from multiple angles to get the clearest story possible.

Thus far, I have been able to identify a specific group of gut bacteria that seem to have a suppressive effect on colitis. Initially, I conducted a replication experiment to determine whether this bacterial group truly had a suppressive effect on colitis. For this, I compared the suppressive effect in germ-free mice and mice that were administered this colitis-suppressing gut bacterial group. As a result, mice with the colitis-suppressing gut bacterial group indeed showed a suppressive effect on colitis.

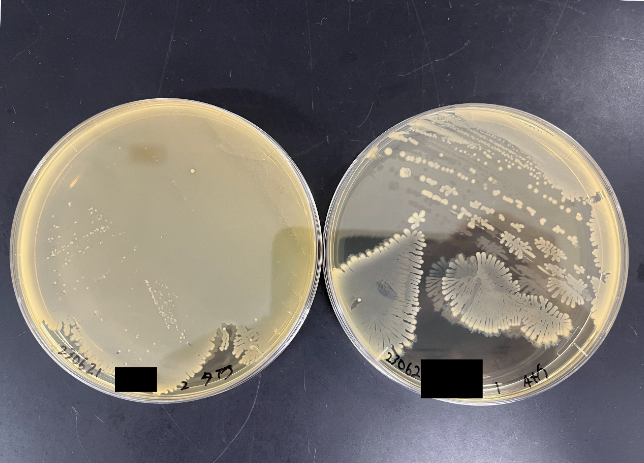

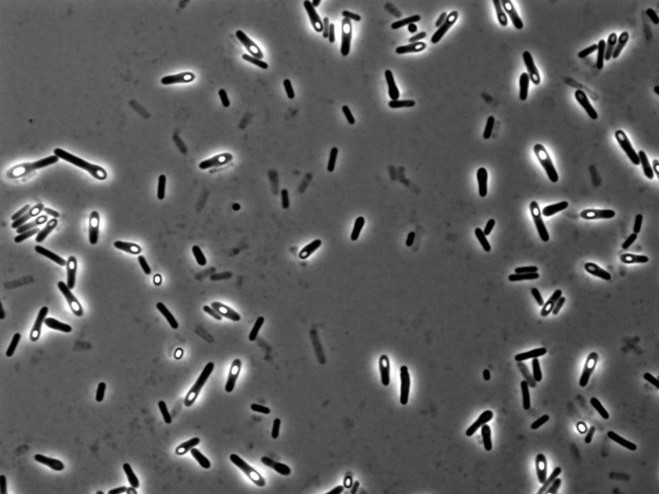

To understand which bacteria within this group were responsible for suppressing colitis, I attempted to isolate the different strains. I cultivated bacteria from this group under various conditions, using different media and under anaerobic states, and managed to isolate approximately 200 individual bacteria. Upon further investigation of their metabolic capabilities crucial for colitis suppression, five of these bacteria were found to potentially have the ability to produce substances vital for suppressing colitis. When I extracted and analyzed the genomic DNA of these five bacteria using next-generation sequencing, it turned out that all five were from the same bacterial species.

Subsequently, I administered this colitis-suppressing bacterium to germ-free mice to evaluate its suppressive effect. However, a single species of the colitis-suppressing bacterium did not show any suppressive effect on colitis. That no significant increase in substances crucial for colitis suppression was observed in the intestines of these mice suggests that the presence of other gut bacteria is also necessary. Moving forward, I aim to isolate other gut bacteria that are needed for this colitis-suppressing bacterium to be effective.

Lastly, I conducted a whole genome analysis of the colitis-suppressing bacterium. Given that no previous reports suggested that gut bacteria produce substances vital for colitis suppression, this finding could be of great academic significance. However, despite several attempts under different conditions, I was unable to extract DNA of adequate quality for analysis. External agencies also faced challenges when trying to extract it. In the future, I plan to explore the conditions appropriate for DNA extraction.

Achieving High Impact

I expect that the detailed molecular mechanism by which rice bran intake leads to colitis suppression can eventually be clarified. In conventional nutritional science, importance is placed on the components contained in foods, and little has yet been elucidated regarding the mechanism of gut microbiota. In my research, I hope to promote a fuller understanding of the role gut microbiota plays in how food intake affects the body. Such findings can be expected to have a high social and academic impact, and I hope to publish them in a well-known international scientific journal. In addition, an application for an international patent will be filed to develop a new therapeutic drug for colitis based on the findings of the colitis suppression mechanism. I thus believe that my research will be able to contribute to patients with unmet medical needs.

Research results must be commercialized in order for them to be disseminated to the public. A patent for an anti-inflammatory agent is scheduled to be granted next year. A new patent is pending in collaboration with a startup company, and our research team is currently in discussions with the company to commercialize the product. We have presented our findings at conferences to promote food developments not only for rice bran but also for many other foods worldwide, and we will be writing papers this year to disseminate our findings.

[1] Takechi R, Alfonso H, Hiramatsu N, Ishisaka A, Tanaka A, Tan L, Lee AH. Elevated plasma and urinary concentrations of green tea catechins associated with improved plasma lipid profile in healthy Japanese women. Nutr Res. 2016;36(3):220–6.

[2] Nakata T, Kyoui D, Takahashi H, Kimura B, Kuda T. Inhibitory effects of laminaran and alginate on production of putrefactive compounds from soy protein by intestinal microbiota in vitro and in rats. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;143:61–9.

[3] Shirosaki M, Koyama T. Laminaria japonica as a food for the prevention of obesity and diabetes. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research. 2011;64:199–212.

[4] Kanai T, Matsuoka K, Naganuma M, Hayashi A, Hisamatsu T. Diet, microbiota, and inflammatory bowel disease: Lessons from Japanese foods. Korean J Intern Med. 2014;29(4):409–15.

[5] Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, Shastri GG, Ann P, Ma L, et al. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell. 2015;161(2):264–76.

[6] Al-Fayez M, Cai H, Tunstall R, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Differential modulation of cyclooxygenase-mediated prostaglandin production by the putative cancer chemopreventive flavonoids tricin, apigenin and quercetin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58(6):816–25.

[7] Islam MS, Murata T, Fujisawa M, Nagasaka R, Ushio H, Bari AM, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of phytosteryl ferulates in colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(4):812–24.

[8] Komiyama Y, Andoh A, Fujiwara D, Ohmae H, Araki Y, Fujiyama Y, et al. New prebiotics from rice bran ameliorate inflammation in murine colitis models through the modulation of intestinal homeostasis and the mucosal immune system. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(1):40–52.

[9] Shafie NH, Esa NM, Ithnin H, Saad N, Pandurangan AK. Pro-apoptotic effect of rice bran inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) on HT-29 colorectal cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(12):23545–58.

[10] Choi JY, Paik DJ, Kwon DY, Park Y. Dietary supplementation with rice bran fermented with Lentinus edodes increases interferon-γ activity without causing adverse effects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Nutr J. 2014;13:35.

[11] Islam J, Koseki T, Watanabe K, Ardiansyah, Budijanto S, Oikawa A, et al. Dietary supplementation of fermented rice bran effectively alleviates dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):747.

[12] Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491(7422):119–24.

[13] Ridenhour BJ, Brooker SL, Williams JE, Van Leuven JT, Miller AW, Dearing MD, Remien CH. Modeling time-series data from microbial communities. ISME J. 2017;11(11):2526–37.

[14] Sonnenburg JL, Bäckhed F. Diet–microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature. 2016;535(7610):56–64.

[15] David LA, Materna AC, Friedman J, Campos-Baptista MI, Blackburn MC, Perrotta A, et al. Host lifestyle affects human microbiota on daily timescales. Genome Biol. 2014;15(7):R89.

[16] Cervantes-Barragan L, Chai JN, Tianero MD, Di Luccia B, Ahern PP, Merriman J, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri induces gut intraepithelial CD4 + CD8αα + T cells. Science. 2017;357(6353):806–810.