Leon Poshai (University of the Western Cape, 2020) used an SRG award to conduct interviews with both local leaders and residents in five South African municipalities to assess the extent to which coproduction—the formalized process by which local governments engage with citizens—can be used to address community problems and enhance the effectiveness of service delivery.

* * *

My research sought to assess the viability of coproduction as a strategy for ensuring that citizens have a voice in the policymaking processes in the context of local governance in South Africa. Coproduction refers to the formalized process by which the government engages with citizens when making decisions that affect them (Khine et al. 2021). In the context of local governance, coproduction involves consulting and engaging with residents and their local leaders when reaching decisions on how services should be delivered. The process of coproduction has been regarded as a best practice for the cogeneration of actionable knowledge to address community problems (Osborne, Radnor, and Strokosch 2016).

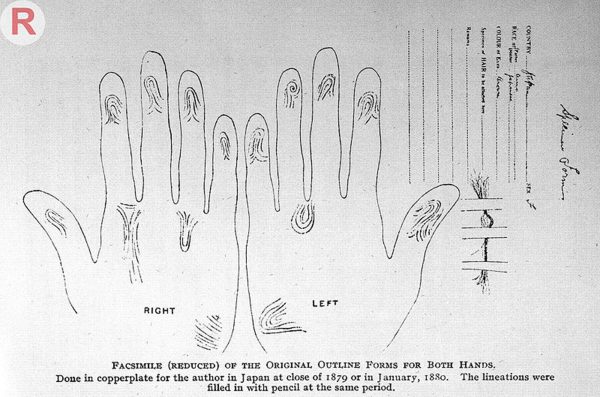

The overall aim of the study was to assess the extent to which the coproduction model can be used to enhance the effectiveness of service delivery in South Africa’s local government institutions. In this regard, the research explored the various measures that local governments in South Africa are using or can use to ensure that there is regular engagement between local government leaders and residents as recipients of services. For example, the photo below shows ward councillors interacting with residents on community development, which can be seen as coproduction in action.

Citizen-government interaction forms the core of the process of coproduction, https://twitter.com/CityofJoburgZA, accessed June 16, 2023.

Through a qualitative research approach deploying the interview method, I was able to interact with residents and local government leaders in five cities in South Africa, namely, Cape Town, Mpumalanga, Pretoria, Limpopo, and Johannesburg. Their selection was based on the fact that they are major municipalities in South Africa, making them a rich social laboratory for the collection of diverse data from a larger population. I combined both convenience sampling and purposive sampling in selecting the participants. Both face-to-face interviews and telephone interviews were used, based on the availability of the participants.

Through the interviews, I managed to obtain a balanced overview of the utility of coproduction from both the residents and local leaders. I traveled to these cities to interact with residents and obtain an in-depth understanding of the issue investigated in its natural context. This enabled me to gain an appreciation of the need for coproduction as a response to the different service delivery challenges facing South Africa’s local governments.

The study was guided by the following research question:

- What are the current strategies for promoting the codesign of policy solutions to address local government challenges in South Africa?

- What can local government institutions in South Africa do to improve their citizen engagement methods toward the codesign of solutions to challenges confronting their communities?

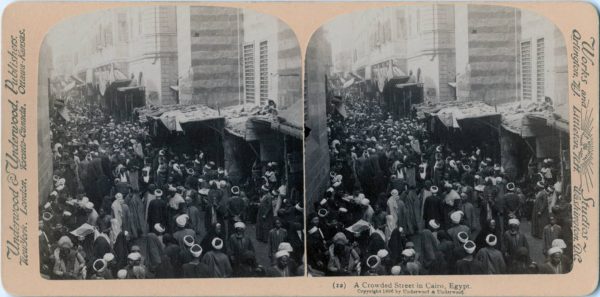

The main findings of the study indicate that in local governance, coproduction is the glue that binds societies together, as it brings the governors (leaders) and the governed (residents) together in defining the problems affecting their communities and in designing appropriate solutions to address those challenges. The photo below shows the leadership-resident interface in a South African local government.

Deliberations between a local leader and residents on policy issues, https://twitter.com/CityofJoburgZA/status/1115171024973312000/photo/3, accessed August 21, 2023.

The study also revealed that coproduction enables the kind of regular interaction between the local leadership and residents that is crucial for local development, allowing for collaboration and idea transfer. Without coproduction, it is difficult for local leaders to know what problems are affecting residents and what solutions are needed to address the problems. Thus, the study found that the development of relevant policy responses to local problems hinged on the engagement or collaboration between the leaders and the residents, which is made possible through coproduction.

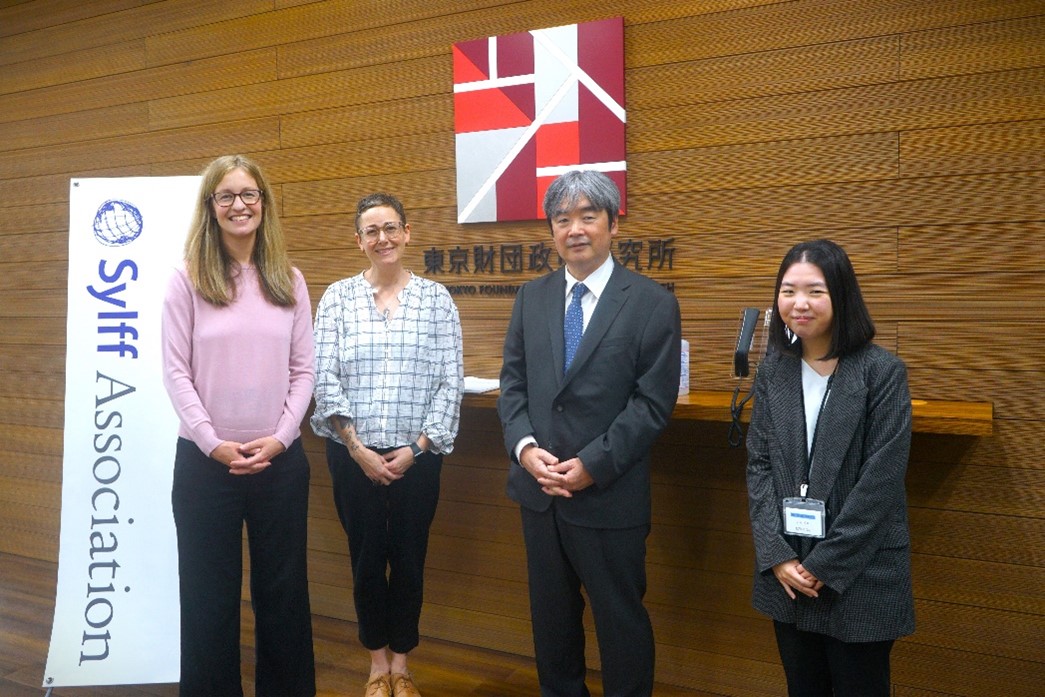

The study also revealed that when coproduction is not practiced, residents often resist the resolutions passed by their local leaders, sometimes leading to protests or unrest in the communities. Thus, citizens expect that they are duly consulted by their leaders in the decision-making process, and when this is not done, they feel that they are neglected. Residents will not support decisions made without their participation. Interactions with residents revealed that the main reason for protests in different South African municipalities was because of the imposition of decisions by their leaders without their input. Picketing at government offices occurs when residents feel that they are sidelined in the formulation of decisions that have a direct bearing on their lives, and this underscores the need for leaders to engage residents in the decision-making process and the need for coproduction. Interviewed residents highlighted that they feel valued if their leaders engage them before making decisions that affect them, and if this is not done, they will protest against that decision as reflected in the image below:

Picketing because of poor government-resident engagement, https://www.groundup.org.za/article/tembisa-residents-meet-councillors-over-reblocking-demolitions/, accessed October 25, 2023.

Residents interviewed in Limpopo noted that coproduction is the only way in which they can share their grievances with their local leaders. They indicated that solutions for community problems should come from the members of the community themselves and not be imposed by their leaders. As such, residents indicated that they expect to be consulted by their leaders, such as mayors, councillors, and municipal managers, when decisions affecting their lives are made. The residents indicated that the main service delivery functions that they expect to be consulted on as part of the process of coproduction include issues of water provision, road construction and maintenance, sewer reticulation, waste management, and general good governance. The views shared by the residents emphasized the need for coproduction, which allows for regular engagement between local leaders and residents in designing solutions to problems faced in their areas.

Furthermore, the study showed that coproduction contributes to greater transparency in local governance. The use of local financial resources (local budget) can be done in a more transparent manner if there is open dialogue and communication between the leaders and the residents, which coproduction enables. In particular, transparency in financial resource utilization is achieved through agreements on the areas of resource prioritization. The existence of a pre-agreed strategic plan on the utilization of financial resources enables residents to monitor if the utilization process is in line with the agreed plans, and this helps to minimize the chances of corruption and abuse of public funds (Bandola-Gill et al. 2023). Interviewed municipal officials in Pretoria and Cape Town indicated that they consult and involve residents in developing local budgets and keep them in the loop regarding financial decision-making. This is a major component of coproduction, which creates a sense of transparency in the utilization of financial resources. The residents also concurred that they are consulted in the budget formulation process, and, as ratepayers, this helps them to check the extent to which their rates are being used for agreed priorities.

The research also established that coproduction is key to bridging the gap between governments and citizens. It represents the principal avenue for citizens and the government to engage on issues that matter most, particularly issues of service delivery, helping to build trust between the leaders and the residents. Trust is a fundamental pillar of sound governance, as it nurtures an honest relationship between the government and the citizens (Campanale 2020). Coproduction engenders dialogue between the government and the citizens, which helps in cosetting the local development agenda and policy priorities.

The study revealed that coproduction should be promoted through public consultations, public opinion surveys, local hearings, and community engagement programs—activities that help provide residents with the necessary information in the decision-making process. Coproduction in South African municipalities creates an open space where residents can share their concerns, offer feedback, and develop proposals for action with their leaders. This helps to ensure that the decisions made by the leaders are resonant with the expectations and realities of the residents. The interview with community leaders in Mpumalanga indicated that the policy decisions made using the coproduction model are highly likely to be responsive to the challenges faced by the communities.

Scholars like Moallemi et al. (2023) have argued that coproduction enables the sharing of information on activities and programs being implemented by the government and helps raise awareness on policy issues. In addition, the process of coproduction leads to greater clarity on the roles that both leaders and residents must play in the efforts to resolve community challenges. Some residents indicated that information on government programs remains erratic, however, as most decisions continue to be made without their input. This raises concerns about the effectiveness of stakeholder engagement in the South African local government system. It has been argued that the disclosure of information allows citizens to gain an understanding of the issues that affect them. Thus, local government institutions are encouraged to promote the proactive disclosure of relevant information in a clear and timely manner.

The topic of coproduction was chosen because it enables an examination of the interface between the local government leadership and residents. The topic provided a formal way of demonstrating why collaborative engagement between the governors and the governed are important. The findings of this study can contribute to society by enhancing understanding of the need for government and residents to collaborate in defining problems and in generating solutions to address them together. These findings can help local government practitioners in different parts of the world develop strategies for engaging residents and formulate relevant solutions to the challenges facing contemporary local government institutions.

References

Bandola-Gill, Justyna, Megan Arthur, and Rhodri Ivor Leng. 2023. “What is co-production? Conceptualising and understanding the co-production of knowledge and policy across different theoretical perspectives.” Evidence & Policy 19(2), 275–298.

Campanale, Cristina, Sara Giovanna Mauro, and Alessandro Sancino, 2021. “Managing co‑production and enhancing good governance principles: Insights from two case studies.” Journal of Management and Governance 25(1), 275–306.

Khine, Pwint Kay, Jianing Mi, and Raza Shahid. 2021. “A Comparative Analysis of Co-Production in Public Services.” Sustainability, 13(12), 6730.

Moallemi, Enayat A., Fateme Zare, Aniek Hebinck, Katrina Szetey, Edmundo Molina-Perez, Romy L. Zyngier, Michalis Hadjikakou, Jan Kwakkel, Marjolijn Haasnoot, Kelly K. Miller, David G. Groves, Peat Leith, and Brett A. Bryan. 2023. “Knowledge co-production for decision-making in human-natural systems under uncertainty.” Global Environmental Change 82, 102727.

Osborne, Stephen P., Zoe Radnor, and Kirsty Strokosch, 2016. “Co-Production and the Co-Creation of Value in Public Services: A suitable case for treatment?” Public Management Review 18(5), 639–653.