In her PhD project, 2020 Sylff fellow Maija-Eliina Sequeira combines ethnographic and experimental methods to explore how the sociocultural environment shapes children’s understanding of social hierarchies. Following a study in Finland, she is currently conducting further research in Colombia using an SRA grant. The outcome of the comparative study will shed light on how children in the two countries differ in their preferences for prestige or dominance and how they develop these preferences.

* * *

Humans must be understood as both social and biological beings; a focus on nature or nurture alone is not enough to explain both the diversities and the consistencies in how humans across the globe structure and live their lives. Instead, underlying universal human cognitive tendencies and capacities, such as the capacity to learn language or the tendency to ascribe agency to nonhuman beings at a certain age, are shaped by various factors including the sociocultural environment within which a child is socialized. This socialization occurs through active processes such as teaching, as well as through more passive exposure to norms, structures, and patterns in the world around them. Certain tendencies and capacities might be taught, encouraged, or nurtured in the growing child, while others are stifled or simply not given attention, depending on local norms, values, and customs—which themselves vary between individuals and across time periods. In short, I consider that children learn what it means to be human within a certain historical setting and in the context of specific social groups—such as their local community, family, and the wider society—and that these factors shape and direct their development throughout their lives.

With this in mind, I took on a PhD project that allowed me to combine “bottom-up” exploratory ethnographic methods—and generate the deep, nuanced understandings of social relationships that they lend themselves to—with the more structured “top-down” experimental methods that enable fruitful comparisons between two groups. Having lived in Colombia for several years before moving to Finland in 2019, I was struck by just how different the two countries are at the societal, familial, and school levels. I knew that such stark differences would provide an interesting and informative backdrop for a comparison of the socialization of children.

Basis of Social Status: Dominance or Prestige

My research explores how children’s sociocultural environment shapes how they understand, use, and navigate through social hierarchies in their everyday lives. Human societies tend to be stratified; they have certain people with more power or influence than others, although such stratification takes many different forms, ranging from more systematized and explicit caste or class systems to very subtle differences in influence according to age, gender, or some other marker of status in a relatively egalitarian society. Research from psychology suggests that an individual’s high status can be built on two different processes: dominance processes, a coercive process based on fear, strength, or intimidation and threat, and prestige processes, which are based on merit and knowledge or on skill in a locally valued domain.[1] Dominance processes are found in many nonhuman primates and other animals, whereas prestige processes appear to be a uniquely human phenomenon, and it has been suggested that prestigious imitation—the tendency of humans to choose to learn from and copy prestigious individuals—might serve as an important social learning mechanism for cultural transmission in human social groups.[2] It is therefore very interesting to consider how and when children learn to identify dominance and prestige and to determine how their sociocultural environment shapes the way in which they react to prestige and dominance.

Research from developmental psychology suggests that children start to develop a basic ability to reason about rank, and particularly to identify dominance, from when they are just months old, which suggests that there are universal cognitive mechanisms underlying the ability. This is supported by the fact that cues of dominance appear to be similar cross-culturally and are also consistent with dominance cues found among nonhuman primates, such as “squaring up” behavior. Prestige, meanwhile, is dependent on local cultural value placed on different skills and behaviors, since what is valued and considered to be an important ability or knowledge varies dramatically across different societies: in one it might be the ability to hunt a specific large animal and in another to sing in a particular pitch, while in others it might be associated with the accumulation of highly specific knowledge about local fauna and flora. Therefore, as children grow and are socialized within a specific sociocultural environment, they must develop a much more nuanced and locally specific understanding of how power and influence are distributed in their society, and they must learn to navigate within these complex systems.

There is cross-cultural variation not only in the understanding of what behaviors are considered prestigious, but also in people’s preference for dominant and prestigious leadership. In societies characterized by instability and resource inequality, dominant-style leadership is considered to be more acceptable and, in some cases, preferable to prestigious-type leadership.[3] In my PhD work, I use a combination of ethnographic and experimental methods to explore and compare how children in Finland and Colombia—two extremely different sociocultural environments—learn, use, and navigate social hierarchies. Colombia has high levels of insecurity and extreme socioeconomic inequality, making it a very different social environment from the equality, stability, and safety net of a generous social security system that Finland is known for. Interestingly, despite these differences, both Colombia and Finland have been named “happiest country in the world” depending on the measures of happiness that are used.[4]

Conducting Research in Helsinki and Santa Marta

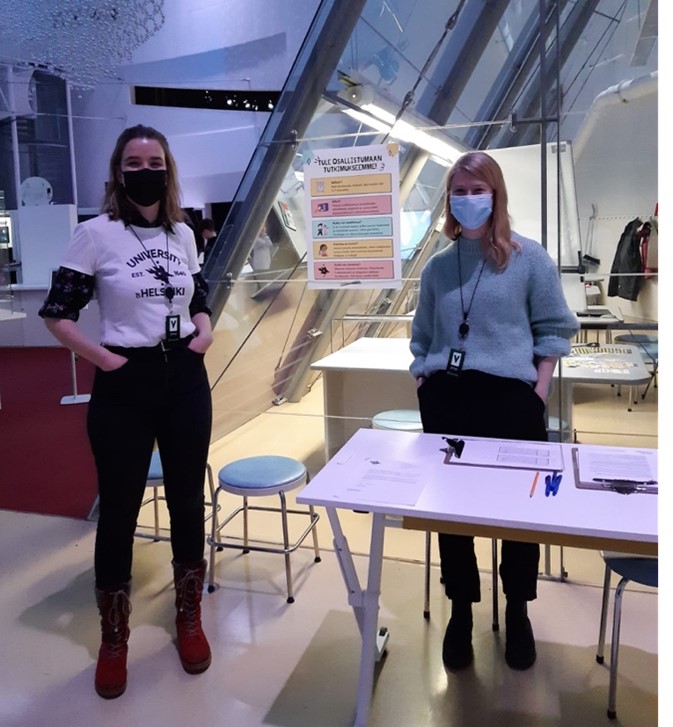

In 2021 I carried out 12 months of ethnographic research with children and families in Helsinki, Finland. This was followed by a series of experiments to investigate whether children (i) infer high social rank from cues of dominance and prestige, (ii) differentiate between prestigious and dominant individuals, (iii) show a personal preference for prestige or dominance, (iv) assign leadership skills to prestigious or dominant individuals, and (v) choose to learn from a prestigious or dominant individual. I tested over 170 children aged 4 to 11 years over a series of weekends from December 2021 to March 2022, basing myself at Heureka science museum. The experimental data are still in the process of being checked for validity, and so analysis has not yet started, but through ethnographic research I have identified a strong aversion to dominant behavior among children living in Helsinki, which I expect to be reflected in the experimental results.

The SRA grant allowed me to hire a research assistant, Valeria Aza Barros, and to collaborate with the research group on cognition and education at the Universidad de Magdalena, Colombia, to replicate the same experiments with children in Santa Marta. After undergoing training and pilot studies via Zoom and checking the translations of the experiments to ensure that they were locally valid, Valeria conducted the experiment with 160 children—our required sample size—between the ages of 4 and 11. Although I am still coding the data, after which they will undergo validity checking and then be analyzed in the coming months, they show signs of very different patterns compared to the data from Finland.

Upcoming ethnographic fieldwork in Santa Marta from August to December 2022 will allow me to contextualize the findings within local norms and hierarchies. This combination of ethnographic and experimental data allows me to interpret the experiments while considering contextual information that might influence the choices and answers of the children during the experiment. Future analyses will reveal whether the children in Colombia really do show a greater preference for dominance over prestige and allow me to determine whether they trust in and prefer dominant individuals to a greater extent than the children in Finland do.

Research in hierarchy is relevant to ongoing debates in many academic fields, such as those related to the evolution and nature of cooperation and morality. However, this project is not just of academic interest; it also holds important societal lessons about the lifelong impact that the early socioeconomic environment can have on individual people and wider society. A preference for dominance in the face of insecurity may have been highly adaptive when the insecurity stemmed, for example, from small-scale warfare with neighboring groups. In such circumstances, dominance may indeed have been the best strategy to ensure survival and prosperity for a community. But such a preference may be maladaptive in modern industrialized societies where a dominant-type leader, who depends on threats and intimidation to gain and maintain power and influence, is unlikely to provide any genuine benefits to people living in situations of insecurity and economic inequality. If individuals raised in more insecure, unequal societies are more inclined to prefer and ultimately choose dominant leaders (such as in elections), they may ultimately be doing more harm than good to themselves and their communities. Dominant leaders are not necessarily the best placed to improve the circumstances of the average citizen and instead might serve to simply perpetuate the cycle of insecurity and inequality that leads to them being selected as leaders and given power in the first place.

[1] J. T. Cheng, “Dominance, Prestige, and the Role of Leveling in Human Social Hierarchy and Equality,” Current Opinion in Psychology 33 (June 2020): 238–244, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.10.004.

[2] M. Chudek, S. Heller, S. Birch, and J. Henrich, “Prestige-Biased Cultural Learning: Bystander’s Differential Attention to Potential Models Influences Children’s Learning,” Evolution and Human Behavior 33, no. 1 (January 2012): 46–56, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2011.05.005.

[3] R. Ronay, W. W. Maddux, and W. von Hippel, “Inequality Rules: Resource Distribution and the Evolution of Dominance- and Prestige-Based Leadership,” The Leadership Quarterly 31, no. 2 (May 2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.04.004.

[4] D. Roos, “Colombia, Not Finland, May Be the Happiest Country in the World,” HowStuffWorks.com, March 26, 2018, https://science.howstuffworks.com/life/inside-the-mind/emotions/colombia-not-finland-may-be-happiest-country-in-world.htm.