Elvisa Frrokaj is a psychologist-psychotherapist (MSc, PhD-C.) and a former Sylff fellow at the University of Athens. She discusses the impact of COVID-19 on mental health, describing the detrimental influence of the pandemic on mental health, which, as studies are beginning to show, is in jeopardy.

***

The Importance of Solidarity in the Face of a Pandemic

In both my capacities as a person and a psychologist at the community level, I share the same passion with the SYLFF Association for making the world a better place. I utterly believe, as we say in Greece, that all people can contribute positively to a situation, each by adding a “small stone.” This means that by cooperating and thus becoming small parts of a large sum, it becomes much easier to tackle the challenges of life. As we humans are social animals, the value of a strong commitment to giving back to the community is of utmost importance to our physical and mental well-being.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was a very representative example of the aforementioned need for commitment to community and a very good opportunity to realize that by working together toward a common goal, we greatly increase the odds to achieving impressive results. The prevention of the spread of coronavirus depends on our individual responsibility, intertwined with collective-community responsibility.

Profound, Unprecedented Changes

When the first measures against the COVID-19 pandemic were enforced around the world, I was shocked, as I could foresee the impact the unprecedented restrictions in personal freedoms would have on public mental health. More particularly, in Greece between March and May 2020 we were in full lockdown. In order to leave home, we were required to send a text message stating the reason for moving. The same applies now for many countries in Europe, as a second lockdown is becoming part of our lives.

For the Western world, this state-enforced control over highly valued personal freedoms is unprecedented and takes a heavy toll on the individual’s mental state. The current situation is something that most of us could never have imagined to ever experience. In myself as well as in my clinical experience as a psychologist, I am seeing a broad palette of negative emotions: surprise, fear, anger, sadness, disappointment, and a sense of insecurity and vulnerability regarding our and others’ health. What is becoming more and more apparent is that COVID-19 will not leave us unscathed. The impact to mental health is happening; it is wide. and it is deep.

As a professional I am seeing the same symptoms, emotions, and thoughts. This new condition is affecting individuals at a personal, interpersonal, and communal level. The common feeling to all is that they do not know the duration of the profound changes they are forced to incorporate in their lives. “Until when?” and “After this, what?” are the most prevalent questions. The inability to make any safe predictions regarding the duration of the pandemic increases the stress on people, who feel helpless due to the perceived lack of control of the situation. For all these reasons, mental health and well-being are in jeopardy.

Scientific Studies Confirm the Observations

The crisis caused by the ongoing pandemic is a new, unknown, and unprecedented challenge that seems to have mentally affected a vast number of people. Recent studies have shown that COVID-19 constitutes a new stress factor or a trauma (Gorwood and Fiorillo 2020), causing several problems, such as intense stress of the unknown, frustration, anger, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and several other mental disorders (Shuja, Aqeel, Jaffar, and Ahmed 2020). Patients with mental disorders seem to have been affected more. A strong correlation has been documented between higher exposure to the effects—direct or indirect—of the pandemic and loneliness, depression, and anxiety disorders (Hoffart, Ebrahimi, and Johnson 2020).

The mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic may be profound, and there are suggestions that suicide rates will rise, although this is not inevitable. Suicide is likely to become a more pressing concern as the pandemic spreads and has longer-term effects on the general population, the economy, and vulnerable groups. Preventing suicide therefore needs urgent consideration (Gunnell et al. 2020). An area of key concern is the potential of the conditions caused by the pandemic to exacerbate existing psychiatric conditions and influence the manifestation of their symptoms. For instance, patients with paranoid psychosis seemed to have increased illusions under particular COVID-19-related conditions (Coogan, Faltraco, and Thome 2020).

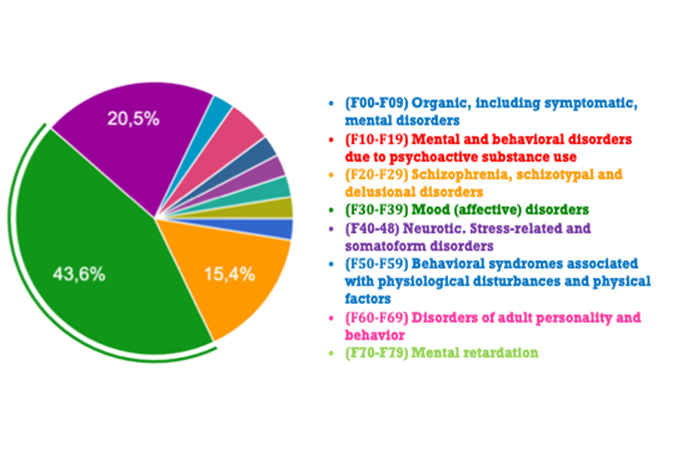

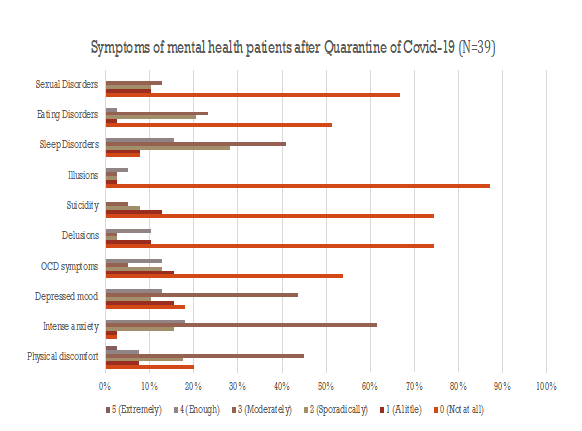

As psychologists at the community clinical level, Ms. Iliana Fylla (psychiatrist, scientific director of the Mobile Mental Health Unit of Child and Adolescent Center, KMPSY, on the island of Chios, Greece) and I studied the consequences of COVID-19 on the psychopathology of our patients after the lockdown that was enforced from March to May 2020. Our studies documented the worsening of mental health among a sample of 450 patients of KMPSY. Thirty-nine of the patients claimed to have experienced a worsening of their mental health after the pandemic. Figures 1 and 2 below illustrate these findings. This study was published at the 28th Panhellenic Psychiatric Conference held in Thessaloniki, Greece, from October 29 to November 1, 2020.

Figure 1. Mental Health Disorders (ICD-10)[1]

Figure 2. Symptomatology after Covid-19 (ICD-10)

More specifically, Figure 1 shows the percentage of the symptoms of mental health patients that were claimed to have worsened. Among all our psychiatric patients (total patients: 450), 39 patients presented a worsening of psychopathology. Figure 2 shows in detail the degrees of worsening of mental health symptoms after lockdown. Thirty-nine of 450 psychiatric patients seemed to have more illusions, delusions, suicidal thought, sexual disorders, and so forth.

In sum, the results of our study confirmed the findings of other studies and showed that 11.5% of mental health patients at KMPSY presented recrudescence in their psychopathology (79.0% women, 20.5% men).

Reviews have shown that this pandemic has been compared to natural disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis, wars, and international mass conflicts, but in these situations the threat is recognized easily, whereas in pandemic the threat is invisible, could be anywhere, and could be transmitted from any person nearby (Gorwood and Fiorillo 2020). The pandemic has created many problems. In this study patients with “affective disorders” presented more intense symptoms. Some of them also had suicidal ideation, increase of compulsions, illusions, and delusion. The best way to confront these consequences is to reinforce and enhance the care support network.

Actions for Public Mental Health

In April 2020 the Psychology Association of Chios took a series of actions to raise awareness in the local community about COVID-19 and foster and reinforce the mental health of people with useful tips and advice. As part of these actions, we gave an interview on local television (https://bit.ly/3519HHl), in which we talked about the psychological impact of the pandemic on young and older people. Understandably, people experience negative feelings such as anger, despair, and depressive symptoms that are caused by the lockdown (April–May 2020). Lockdown affects not only mental health patients but also people who have not had mental health issues before. We tried to propose constructive ways of better managing the situation.

After that, we created a small video (https://bit.ly/3evzCtH ) as an advertisement with a social message—“Keep the coronavirus away and be safe”—in which each psychologist expressed feelings and emotions about COVID-19. Finally, we published articles with tips on how to confront the situation. This multifaceted approach helped people in the local community to stay positive, reduce stress, and avoid panic. I believe that such organized action from professional and scientific organizations can effectively help people confront the situation and the impact of COVID-19.

Useful Tips

- Read reliable sources that are based on scientific data to avoid misinformation, which implies more stress.

- This situation is unprecedented on a global level. The feeling of “helplessness” is expected but renders us more vulnerable mentally. Try to find ways to manage this feeling by being creative or dealing with things that make you happy and positive.

- Find alternative ways of communicating with friends by socializing and having fun using tools that modern technology offers (e.g., Skype, Zoom, Google Meet). It is an opportunity to communicate with our friends and other people or to spend your time by watching interesting videos on YouTube.

- Listen to music, read a book, or exercise to improve mental health and well-being.

- Provide support and dedicate time to elderly people who may feel lonely or to your children and family. Try to show empathy if they are afraid or help them psychologically by listening carefully to their concerns and trying to rationalize them.

- Be positive and focus on what you can control.

To Sum Up

This undoubtedly is a difficult and challenging period, but we can find ways to adapt and be happier living through it, even though there are radical changes in our daily life. It is crucial to focus on the present, in the “here and now,” and to the things that we can control. It is a period that shall pass and may present a good chance for all of us to treasure those little things in our lives, the most precious, which sometimes we take for granted or ignore altogether.

Let’s hope we will get through it soon.

Be strong and take care!

References

Coogan, A.N., F. Faltraco, M. Fischer, and J. Thome. 2020. “COVID-19 Paranoia in a Patient Suffering from Schizophrenic Psychosis: A Case Report.” Psychiatry Research 288 (11).

Fiorilo, A. and P. Gorwood. 2020. “The Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Implications for Clinical Practice.” European Psychiatry 63 (1), e32: 1–2.

Gunnell, D., E. Arensman, K. Hawton, and L. Appleby. 2020. “Suicide Risk and Prevention during the COVID-19 {andemic.” The Lancet Psychiatry 7 (6).

Hoffart, A., S. U. Johnson, and O. V. Ebrahimi. 2020. “Loneliness and Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk Factors and Associations with Psychopathology.” Retrieved from psyarxiv.com/j9e4q. DOI: 10.31234/osf.io/j9e4q

Shuja, K.H., M. Aqeel, A. Jaffar, and A. Ahmed. 2020. “COVID-19 Pandemic and Impending Global Mental Health Implications.” Psychiatria Danubina 32 (1): 32–35.

[1] ICD-10 is the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), a medical classification list by the World Health Organization (WHO).

I have always wanted to be the sort of person who can be helpful in a time of need; to know not only that I can help if needed but that the type of help I can provide is useful. It is one of the things that led me to become a psychologist. But if I am honest with myself, there are many days when I feel like I fall short. As I sit and reflect on life, I often feel an internal pull toward doing more for others: to give more, be more, and have more of an impact. Too often, I think of the “big” things I wish I could do or might do in the future to be useful. However, during these times, it is easy to discount the small and perhaps equally important things we can do today to be helpful. It is my intention to focus not only on the big things in the future but also on the small things and the small ways in which I can be more outwardly focused today.

I have always wanted to be the sort of person who can be helpful in a time of need; to know not only that I can help if needed but that the type of help I can provide is useful. It is one of the things that led me to become a psychologist. But if I am honest with myself, there are many days when I feel like I fall short. As I sit and reflect on life, I often feel an internal pull toward doing more for others: to give more, be more, and have more of an impact. Too often, I think of the “big” things I wish I could do or might do in the future to be useful. However, during these times, it is easy to discount the small and perhaps equally important things we can do today to be helpful. It is my intention to focus not only on the big things in the future but also on the small things and the small ways in which I can be more outwardly focused today.