If there is one profound truth about ethnography, it is that intimacy,

and not distancing, is crucial.

(Fine and Abramson 2020, 1)

Sara Nikolić, a 2020 Sylff fellow, has had to conduct ethnographic fieldwork under the coronavirus pandemic. In this candid account of how the challenge affected her, emotionally as well as in terms of the course of her research, Nikolić says the experience reinforced her love of ethnography and her belief that it is not interchangeable with other methods.

* * *

Starting fieldwork and facing the most significant academic endeavour in a young researcher‘s life is probably never easy. Starting fieldwork in your neighbourhood may sound like a good idea—only until the first wave of the doubt to your research site, the ability to set boundaries and juggle the insider perspective engulfs you. However, starting fieldwork in a densely populated large housing estate under the “first wave” of a global pandemic never sounded like a good idea.

“The expected delay in collecting data will abort many ethnographies. COVID-19 and its future viral siblings may deter those who would pursue ambitious field studies”. However, my research is not really that ambitious. So I try. In weeks when the number of infected seem to be declining, when everyone around me is healthy and when I manage to overcome typical postgraduate insecurities, I keep trying.

These lines are a testament to my confrontation with the flagrant fact that it is not entirely up to me—that I have chosen to relinquish control. In that sense, this essay is an attempt to become aware, articulate and accept how the coronavirus pandemic has affected the course of my doctoral research. This essay is an intimate confession about waiting and learning patience rather than about concrete adjustments of urban ethnography methodology to the crisis that has befallen us. In the following lines I will try to reconstruct the pandemic induced research challenges that led me to reinforce my love of ethnography and the value-laden belief that it is not interchangeable with other qualitative methods.

Alterations in a two-storey residential unit in blok 70, New Belgrade. Photo: Dušan Rajić

Strict curfew introduced by the Serbian Government in March 2020 prohibited people over the age of 65 from leaving the house and occasionally prohibiting younger citizens from leaving their homes for up to 84 hours. When a vibrant and pulsating city dies abruptly, when its citizens’ movement is more restricted than during the bombing, little of the urban life remains for us, researchers of the everydayness, to explore. In the COVID-19 urban landscape of Belgrade—and any other city—intimate, in-person human subject research was (unofficially) prohibited, making ethnography an almost impossible method. Not only did conducting research seem impossible to me at the time, but the very idea of denying the situation we were in deeply disturbed me. The repulsion was so strong that it paralysed me even to dare to approach my neighbours, the rare passers-by who enjoy the spring sun, or the “privileged” individuals who were allowed to walk their dogs, with a request to participate in the research that had nothing to do with our current lifeworlds.

However, hundreds of photographs, dozens of folders, transcripts, voice recordings, several “smell maps” and a few new acquaintances testify that I have not given up. Nevertheless, for senso-biographic approach and focusing on smell-evoked memories of urban environment that form the backbone of my doctoral research, as well as for the informants’ photographic diaries not to become (only) testaments of life under siege by the virus, I had to wait for the “first wave” to come to an end.

I don’t know what the smell of my building would be, before this, I would probably say mould from the basement or the smell of cigarettes in the elevator, but all I feel now is chlorine. It smells like a kindergarten. (M, blok 45, female)

One of my main research interests—self-management in socialist era large housing estates—lurked behind every freshly disinfected staircase. Many buildings’ occupants self-organised into weekly or even daily cleanings to keep the entrances and corridors clean and their families or flatmates safe from the virus. In improvised protective equipment consisting of colourful scarves tied over their faces, rubber gloves and old clothes, armed with their buckets, rags, brooms and mops and the last remaining Domestos or any other chlorine-based disinfectant provided by the municipality, these female troops regained control of the space for the benefit of all. As if taking control of the cleaning schedule, maintaining a routine, following the prescribed steps and performing it together for a moment made the situation outside seem less uncertain.

Bestowing details of these events I recognised as an initiation into the house council simply seemed too intrusive. I hesitated and refused to keep a journal record about self-organized cleaning episodes and to reiterate muffled staircase gossip I overheard during these rites of passage. It almost felt treacherous as in a moment of crisis I perceived my role in the apartment building as a tenant, a neighbour and a girl next door—rather than a cold, rigid and objective researcher.

Therefore, a fellow researcher reading this essay could assume that the research’s explicit part—such as interviews—went better than sketching notes and palpation of the neighbourhood pulse based on informal encounters. A reader could also assume that I, being a girl next door, had no trouble recruiting my neighbours. However, that assumption would be wrong. The fact that I lived close by and was a few minutes’ walk from them, that I was a friendly face they saw on their evening strolls was simply not enough. Nor was the fact that I knew some mutual friends and shared the local references. Lastly, the incentives that I could offer under the Sylff fellowship were irrelevant and insufficient. None of that matters when the danger from an infection is so tangible, and your family members are chronically ill, or you are pregnant or homeschooling your children, or someone close to you has passed away. And on my part, as a vulnerable and empathetic researcher, I could not give up the contacts I built under those trying circumstances and the trust I gained. To this day, I haven’t been able to use some deadline as an argument to recruit new, healthy, childless or carefree informants instead of ones who expressed interest and indicated trust, but their participation was postponed due to objective circumstances.

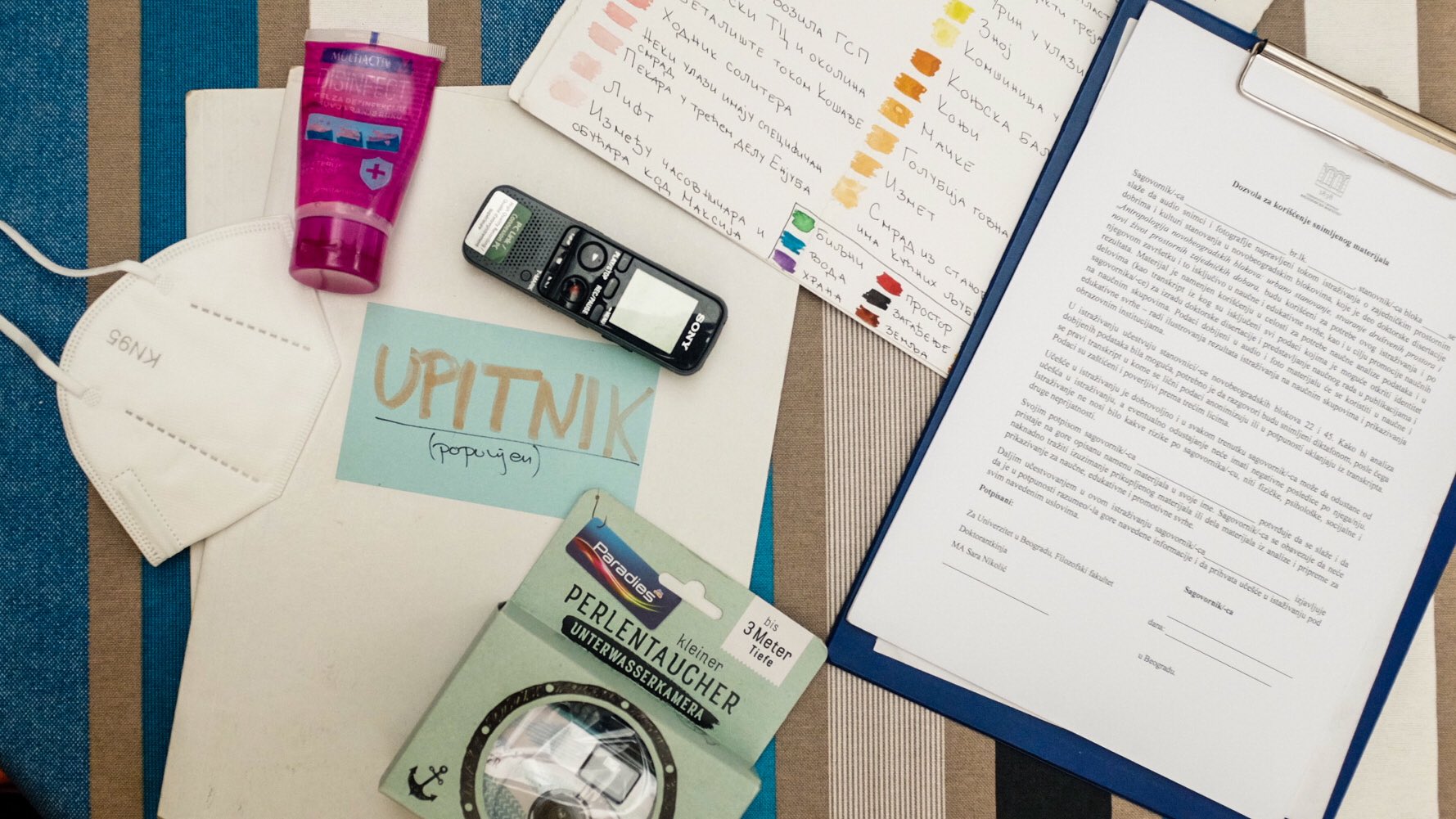

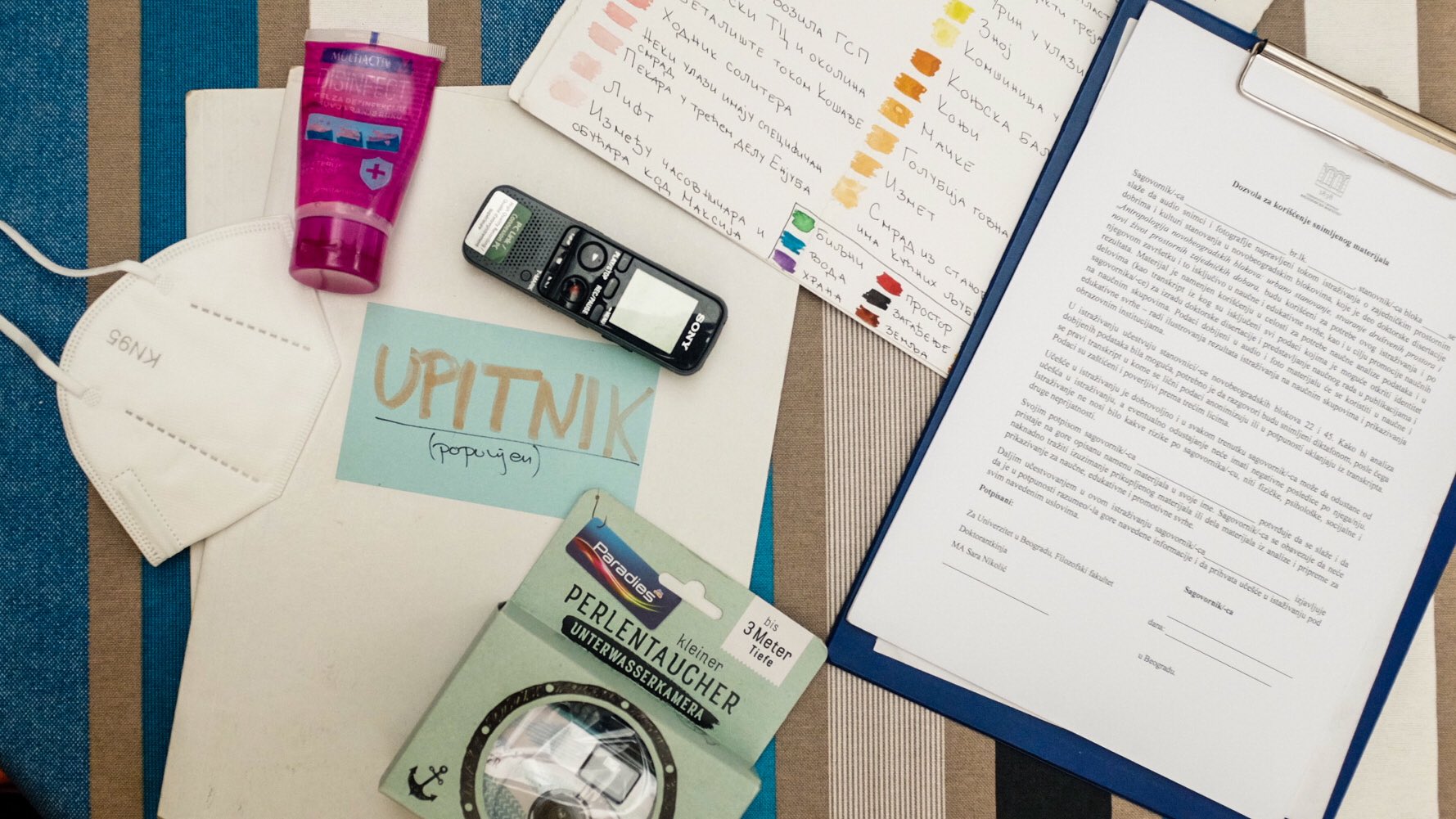

Ethnographic kit under COVID-19. Photo: Sara Nikolić

As a trained ethnographer, I learned about great heroes who went into the wilderness, who “through toughness and perseverance . . . overcome entry barriers”. I, of course, looked up to them. I too wanted to become a hero who overcame the ethnographic odds.

The reality is that I was anxious, frustrated, and impatient. I envied colleagues who enjoyed moments of privilege where they “finally have time to write”. The rising academic pressure, the “figure-it-out-on-your-own” University policy, the “just send me any chapter you have, and we will count it an exam” helping hand of my professors, the crowdsourced documents that offer solutions for “avoiding in-person interactions by using mediated forms that will achieve similar ends” seemed to conflict with the immersion aspect of ethnography I strived for.

These attempts to stay loyal to the ethnography I believe in bring along many pursuits to establish contact with potential respondents, many cancelled or indefinitely postponed meetings, many unanswered calls and messages, and too many sympathetic shrugs. Moments of elation are quickly followed by ones of letdown and despair. I try to push forward. Sometimes I slip or get lost along the way. Sometimes I try to fix it, reinvent my entry strategy, and rely on snowballing instead of a more organic approach. Seeing that I am only halfway in the process of collecting “the deep data”, I cannot refer to the quality and density of the obtained material.

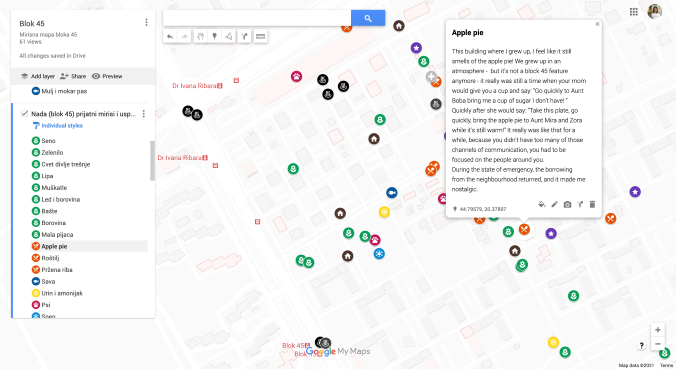

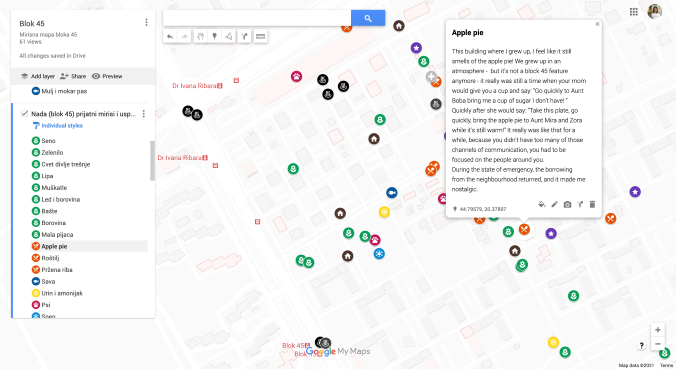

Working version of the “smell map” of Blok 45, New Belgrade. Source: Sara Nikolić

We will take a walk outside, in the fresh air and try to grasp your neighbourhood’s smells, and we will both wear masks. It does not interfere with the quality of the recording—I often explain to my potential informants. Smell mapping while wearing (K)N95 masks, however, does not really work. Instead of fleeting but current and vivid neighbourhood smells that we could not detect while wearing masks, during our strolls we frequently evoked childhood memories intertwined with the ubiquitous scents of the area, such as linden blossom or sludge.

Ding dong! The sound of footsteps, the unlocking of doors and clumsy contactless greetings. Just there, I would usually insist on taking off my shoes, as is the epidemiological recommendation and custom in this area. Furthermore, as good hosts, as an expression of respect for the guest, they would insist that I leave the shoes on. After those initial negotiations at the front door, I would get a bottle of alcohol to disinfect my shoes and mobile phone upon entering the apartment. And then, still from a distance, a hand gesture to signal in which direction the toilet is so that I can wash my hands before the interview. When the weather was nice, we would spend visits to the apartment on the balconies or with the windows open, sitting within a reasonable distance.

On a sunny September day, when everything was going at a good pace, the unglamorous and petty disappointment came. It was caused by an informant’s rejection to invite me into his apartment for the final interview, although it was agreed in advance. Of course, I did not let the injured ego peek outside, so I played it cool. However, I was still ashamed of my feelings, of the vanity that flooded me. Why did I take it so personally? Wasn’t I the one who told him he has the right to give up at any moment and set boundaries in which he feels comfortable and safe? How could I not have understood the respect he had for advised physical distance? Have I forgotten that I am not merely a researcher but a possible vector too?

Object elicitation and disinfection in the informant’s apartment. Photo: Sara Nikolić

Although I do not attach half the importance to this episode today as I did on that September day, it encouraged me to think about how many people passed through my apartment from March to September? Very few, and I knew them all. I trust them. I know how responsible they are, how much they follow all the recommendations, how much they care and how much they are in solidarity with the people around them. Is it possible that I was so upset because I interpreted this man’s responsibility or privacy as distrust? So what if he was distrustful? Don’t we all have the right to be distrustful at a time when we are in danger from an “unknown enemy”, when the media is co-opting military rhetoric, when contradictory information and mutually exclusive recommendations are coming from all sides? Aren’t we, citizens of a country that declared coronavirus “the most ridiculous virus in the world”, and shortly afterwards deprived us of freedom of movement, justifiably distrustful towards anything and anyone? Amidst growing distrust that surrounds us, how can we closely and intimately research something as personal as home, something as inseparable from issues of trust as community relations and self-organization?

Much as we might adapt our research plans to alternative methods in the current crisis and agree to data-oriented techniques such as structured interviews, we must not forget the importance of the immersive experience and deep hanging out for ethnography. As this crisis helped me rediscover that ethnography is not interchangeable with other qualitative methods, I realised that the pragmatic choice to take time was ideological. The choice that was the only possible one, and the one that I needed—to embrace the vulnerable researcher within me and remain faithful to ethnography at the cost of breaking deadlines and delaying my studies. The choice to advocate for slow science. A science that is not an end in itself, a science that is not cruel and does not require sacrifices or preposterous heroic deeds, a science that does not exploit or endanger the subjects under study. That is science based on questioning and building trust instead of taking it for granted.

Reprinted from https://www.ijurr.org/spotlight-on/becoming-an-urban-researcher-during-a-pandemic/credence-chlorine-and-curfew-doing-ethnography-under-the-pandemic/