AUC 100 years

January 19, 2021

January 19, 2021

January 7, 2021

By 25159

The article describes how the people of the Indian Sundarbans delta, who have adopted migration as a means of survival in an ecologically fragile deltaic region in eastern India, have been affected by the combined impact of the global pandemic and tropical cyclone Amphaan, which struck India in 2020.

* * *

Inhabitants of Banashyamnagar in the Sundarbans queue for disaster relief while trying to maintain social distancing norms to prevent the spread of COVID-19. (Picture by Amartya Ray)

The word cyclone was coined in the city I am writing from, Calcutta. A colonial officer, Henry Piddington studied tropical storms peculiar to the Bay of Bengal and named them cyclones after the Greek word ‘kuklōma', meaning the coil of a snake. When in 1853, the colonial government decided to build a port in the lush green deltaic region south of Calcutta, Piddington wrote an anxious letter to the then Governor-General of British India, Lord Dalhousie, to explain how the plan might not succeed should a cyclonic storm strike. True to his word, fourteen years later, a ferocious storm razed the newly built Port Canning to the ground. Nearly two hundred years after Henry Piddington’s lifetime, the forested deltas of present-day India and Bangladesh, called the Sundarbans, continue to reel under severe environmental stress.

People began settling in the hostile climate of the Sundarbans during the colonial period when the British Raj decided to deforest much of the largest mangrove forest in the world, and the natural shield of the eastern portion of the Indian mainland against sea storms, for agricultural revenue. Because of their low-lying, riverine and coastal setting, inhabitants of the region have never been unfamiliar with the threat of cyclones. But those living in the ‘transition’ zone between ‘stable’ inland areas contiguous with the mainland and ‘core’ seaward areas of legally protected mangrove forests, remain most vulnerable to environmental hazards. Located along major tidal rivers, only 23 percent of the roughly 1.5 million inhabitants of the transition zone had access to safe water in 2011, while less than 2 percent could access storm shelters.

The region faces a basket of environmental hazards round the year. It experiences sudden-onset extreme weather events in the form of about nine cyclonic storms a decade, a third of which are severe. In the recent past, Sidr (2007), Aila (2009), Phailin (2013), Hudhud (2014) and Bulbul (2019) have struck the Sundarbans with cycles of immense destruction. In the background of recurring cyclonic storms, are slow-onset environmental hazards that people have lived with for centuries. Some of these, such as a rising sea level, salinisation of soil and water, loss of ecosystem services and failure of the ring of embankments built to protect the region from erosion have led to decreased access to safe drinking water, lack of food security and inadequate WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) facilities. Salinity in soil has reduced land productivity in a region primarily dependent on agriculture as its chief livelihood strategy. Salinity in water sources and lack of piped water supply have resulted in poor health outcomes and high diarrhea-related mortality, especially among children. This year, however, the people of the Indian Sundarbans face a triple crisis. In the fourth week of May, the deadliest tropical cyclone to have ever impacted the Bay of Bengal, Amphan, coincided with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in the background of deep-seated impacts of slow-onset hazards.

The Sundarbans is celebrated as a World Heritage Site, a recognition accorded by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to the rich biodiversity of the Indian Sundarbans in 1987 and of the Sundarbans of Bangladesh in 1997. But its 7.2 million inhabitants confront as part of everyday life a web of slow-onset and sudden-onset climate stress and socio-economic vulnerability that lead them to migrate from the region in search of work to adapt to their hostile living conditions. There are also instances of environmentally-induced displacement in the region. The islands of Lohachara, Suparibhanga and Bedford have already submerged in the sea, while Ghoramara has shrunk to a fourth of its original size, witnessing the displacement of thousands to the neighbouring island of Sagar. Climate change and human activities such as tidal-based aquaculture and overexploitation of natural resources further aggravate the impact of environmental hazards in the region. In fact, sea level rise in the Sundarbans does not result only from eustatic processes, or the thermal expansion of sea water due to global warming, but also from isostatic processes, which is a local decrease in land level due to compaction of soil and deltaic subsidence. Isostatic processes contribute to about 3 to 8 millimetres of sea level rise in the region every year.

Environmental migration has no locus standi in international treaty law at present, nor are there any national legal provisions in place that can support or compensate migration from the Sundarbans. Policies on disaster risk management in India are limited to disaster relief that address extreme-weather events alone. They do not include instances of displacement or migration due to environmental stress. Additionally, environmental change cannot always be separated from other drivers of migration, and it is therefore difficult to identify environmental migration as a discrete phenomenon. Cross-country research has shown environmental migration to be a multicausal affair, with factors of extreme poverty, socio-political insecurity and environmental dangers reinforcing each other in driving people to move. It is no different in the case of the Indian Sundarbans, where the living standards of the people are grave. According to a household survey conducted after Cyclone Aila of 2009, in a typical group of thousand residents, 510 people, most of them children, were found to suffer from some form of malnutrition. The survey revealed three broad patterns of migration from the region: long-term migration to distant big cities in search of work, seasonal migration during paddy-sowing and harvesting seasons to neighbouring districts as farm labour, and short-term migration to the nearest big city, Kolkata, for informal employment in masonry, sanitation services and public works. Although these people are not called forced environmental migrants because the term does not legally exist, environmental hazards and climate change contribute to the absence of employment opportunities for which they migrate. Extreme poverty both arises from and contributes to their vulnerability to environmental hazards.

When COVID-19 broke out in March, India witnessed the imposition of a nation-wide lockdown with only four hours’ notice. Businesses shut, streets were emptied, factories stopped and workers were laid off. Over 90 percent of India’s population work in the informal sector, and migrants form a large share of it. With abject poverty at source and little income in big cities, migrant workers in India straddle extreme uncertainty and vulnerability even without a pandemic or its economic fallout. But with the COVID-19 crisis, loss of work, and the government’s stringent lockdown rules, they were left with no choice but to return to their home states.

From very early into the lockdown, special repatriation flights were arranged to bring back Indian citizens stuck in foreign countries, but no effective measure was undertaken to facilitate the reverse exodus of migrants from cities or to provide them with alternative sources for earning a living. In a recent report by the country’s central bank, push factors such as high cost of living in urban areas, loss of employment, uncertainty of the lifting of the lockdown, and limited access to social and unemployment benefits, combined with pull factors such as the onset of winter harvesting season, employment opportunities in public assistance programmes in their native villages, and wanting to feel secure with their families, acted as major drivers of the massive reverse migration of migrant workers. With inter-state transportation halted, millions of migrants began a long journey home with babies and bundles under their arms, an unrecorded number of them collapsing on the way. By late March, about 250,000 to 300,000 migrants had returned to the Sundarbans alone. This amounted to an increased threat of disease in the islands, loss of remittances in migrant households, increased pressure on natural resources and an overwhelmed local labour market.

When Category 5 cyclone Amphan struck Bengal and Bangladesh in the afternoon of 20 May this year, inhabitants of the Sundarbans were already neck-deep in trouble. With a surge of return migration, loss of jobs and inadequate public health facilities making living conditions dismal, the cyclone caused irreparable damage to life in the Sundarbans. The 111 mile per hour winds washed away huts, cattle, trees and electric poles, broke through the protective embankments that had been built around the islands and filled paddy fields with seawater. People thronged in school buildings and storm shelters despite fear of contagion. In a month’s time, the spread of COVID-19 surged from 3,103 cases and 181 deaths on the day of the storm to nearly 5,500 cases and over 300 deaths in the region by early June. The state government estimated over 28 percent of the mangrove forests to have been damaged. The storm ripped off the 100 kilometre long nylon fencing that had hitherto prevented tigers from straying into human habitations. Subsistence agriculture, the dominant livelihood for most inhabitants, was badly hit. The agricultural department of the government estimated heavy losses incurred by 1,08,000 farmers across 17,800 hectares of crop field. The surge of brackish water in fields and ponds killed off fishes and rendered fields uncultivable for years ahead. With hundreds and thousands of extra mouths to feed, man-tiger conflicts spiked as islanders began venturing deep into the forests in search of fish, crab, honey and firewood.

When Cyclone Aila had struck in 2009, able-bodied islanders migrated out in search of work. Their families remained behind, living on a thin flow of remittances. But with the devastation of Amphan, a global pandemic showing no sign of decline and an unprecedented surge of return migration into the Sundarbans in early 2020, possibilities for exploring economic opportunities outside the region— the primary means of adapting to environmental hazards at home— remain bleak. The state government announced 827,000 dollars in aid for rebuilding life in the Sundarbans after Amphan while the central government has released 130 million dollars from the National Disaster Relief Fund for the state of West Bengal. But short-term relief cannot reverse the damage caused by Amphan unless supported by forward-looking strategies of overcoming the triple crisis of slow and sudden-onset environmental hazards, poverty and COVID-19 that the region faces today. Some climate experts and economists point to the benefits of planned and managed retreat of inhabitants living in the transition zone to more stable zones over in-situ strategies of adaptation while others point to the dangers of extracting people from their land. But with inhabitants trapped in a public health crisis amid extreme environmental and economic vulnerability, migration will have to be managed and facilitated by the state instead of scraping by with local efforts of building resilience.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank her friend Amartya Ray for his insightful comments. He went to the Sundarbans along with his mother Chaiti Ghoshal with relief for 500 inhabitants of the village of Banashyamnagar on 4 June 2020. Both of them are film actors in India.

Reprinted from the IOM's special blog, https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/blogs/triple-crisis-indian-sundarbans

December 17, 2020

View video message from Sylff Association Chairman Yohei Sasakawa to all members of the Sylff community.

The year 2020 was one in which the world struggled to cope with the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. In response, the Sylff Association secretariat launched an initiative called “COVID-19 Relief for Sylff Fellows,” even as applications for regular support programs had to be suspended.

The relief initiative provided financial support to 328 currently enrolled Sylff fellows from 56 Sylff institutions, enabling them to continue their studies and research toward their degrees. In a show of unity, about 30 members of the sylff community donated a total of more than US$13,000 for this initiative.

Though overseas travel was restricted, we were able to meet fellows online through our first virtual Sylff fellows get-togethers in October and November and a meeting with Chinese Sylff institutions to recognize new fellows in December. Fellows have also been sharing their pandemic-related insights and activities through the “Voices from the Pandemic” section of the Sylff website. We invite you to contribute your “Voice” as well. Please send us your article to sylff[a]tkfd.or.jp ([a] must be replaced by @.)

We will continue to do our utmost to support Sylff fellows during these challenging times. Please visit the Sylff website for announcements of new initiatives and programs.

We wish you all a healthy and safe 2021

Middle row, from left, Mari Suzuki (executive director, Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research), Sylff Association Chairman Yohei Sasakawa, Izumi Kadono (president, Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research), Ichiro Kabasawa (executive director, Nippon Foundation). Top row, Masato Seko (senior program director, Nippon Foundation), Keita Sugai (director), Yoko Kaburagi (director). Bottom row, Sachiko Matsuoka, Yue Zhang, Tomoko Yamada, and Yumi Arai.

COVID-19 Relief for Sylff fellows

Thank You for Your COVID-19 Relief Donations (November 16)

COVID-19 Relief Provided to More Than 300 Fellows, but More Help Needed (September 10)

Applications Closed but Fundraising Continues for COVID-19 Relief for Sylff Fellows (August 3)

Online Fundraising Launched to Enable Sylff Fellows to Continue Their Studies (July 29)

Fundraising Launched to Enable Sylff Fellows to Continue Their Studies (July 21)

Start of COVID-19 Relief (July 17)

Sylff to Offer Fellows COVID-19 Emergency Support, Seeks Donations (June 10)

Support Programs

The status of Support Programs through March 31, 2021

Support Programs and COVID-19, Updated July 22, 2020 (August 6)

Support Programs and COVID-19 (April 6)

Before the outbreak of COVID-19

Mindfulness among Educators in South Africa and Promote Mother and Child Health in Puerto Rico (August 5)

SRA Awardees for Fiscal 2019, Second Round (February 20)

Sylff@Tokyo: Serbia Fellow Researching Legal Principles Connects with Experts in Japan (January 15)

Events

Online Meeting with Chinese Sylff Institutions to Recognize New Fellows (December 16)

Sharing COVID Experiences through Virtual Meetings (November 26)

Voices from the Sylff Community

“Voices” from the Pandemic: Call for Articles on COVID-19 (October 22)

Seventh “Voices” Booklet Now Online and in Print (April 22)

December 17, 2020

By 24113

Elvisa Frrokaj is a psychologist-psychotherapist (MSc, PhD-C.) and a former Sylff fellow at the University of Athens. She discusses the impact of COVID-19 on mental health, describing the detrimental influence of the pandemic on mental health, which, as studies are beginning to show, is in jeopardy.

***

The Importance of Solidarity in the Face of a Pandemic

In both my capacities as a person and a psychologist at the community level, I share the same passion with the SYLFF Association for making the world a better place. I utterly believe, as we say in Greece, that all people can contribute positively to a situation, each by adding a “small stone.” This means that by cooperating and thus becoming small parts of a large sum, it becomes much easier to tackle the challenges of life. As we humans are social animals, the value of a strong commitment to giving back to the community is of utmost importance to our physical and mental well-being.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was a very representative example of the aforementioned need for commitment to community and a very good opportunity to realize that by working together toward a common goal, we greatly increase the odds to achieving impressive results. The prevention of the spread of coronavirus depends on our individual responsibility, intertwined with collective-community responsibility.

Profound, Unprecedented Changes

When the first measures against the COVID-19 pandemic were enforced around the world, I was shocked, as I could foresee the impact the unprecedented restrictions in personal freedoms would have on public mental health. More particularly, in Greece between March and May 2020 we were in full lockdown. In order to leave home, we were required to send a text message stating the reason for moving. The same applies now for many countries in Europe, as a second lockdown is becoming part of our lives.

For the Western world, this state-enforced control over highly valued personal freedoms is unprecedented and takes a heavy toll on the individual’s mental state. The current situation is something that most of us could never have imagined to ever experience. In myself as well as in my clinical experience as a psychologist, I am seeing a broad palette of negative emotions: surprise, fear, anger, sadness, disappointment, and a sense of insecurity and vulnerability regarding our and others’ health. What is becoming more and more apparent is that COVID-19 will not leave us unscathed. The impact to mental health is happening; it is wide. and it is deep.

As a professional I am seeing the same symptoms, emotions, and thoughts. This new condition is affecting individuals at a personal, interpersonal, and communal level. The common feeling to all is that they do not know the duration of the profound changes they are forced to incorporate in their lives. “Until when?” and “After this, what?” are the most prevalent questions. The inability to make any safe predictions regarding the duration of the pandemic increases the stress on people, who feel helpless due to the perceived lack of control of the situation. For all these reasons, mental health and well-being are in jeopardy.

Scientific Studies Confirm the Observations

The crisis caused by the ongoing pandemic is a new, unknown, and unprecedented challenge that seems to have mentally affected a vast number of people. Recent studies have shown that COVID-19 constitutes a new stress factor or a trauma (Gorwood and Fiorillo 2020), causing several problems, such as intense stress of the unknown, frustration, anger, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and several other mental disorders (Shuja, Aqeel, Jaffar, and Ahmed 2020). Patients with mental disorders seem to have been affected more. A strong correlation has been documented between higher exposure to the effects—direct or indirect—of the pandemic and loneliness, depression, and anxiety disorders (Hoffart, Ebrahimi, and Johnson 2020).

The mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic may be profound, and there are suggestions that suicide rates will rise, although this is not inevitable. Suicide is likely to become a more pressing concern as the pandemic spreads and has longer-term effects on the general population, the economy, and vulnerable groups. Preventing suicide therefore needs urgent consideration (Gunnell et al. 2020). An area of key concern is the potential of the conditions caused by the pandemic to exacerbate existing psychiatric conditions and influence the manifestation of their symptoms. For instance, patients with paranoid psychosis seemed to have increased illusions under particular COVID-19-related conditions (Coogan, Faltraco, and Thome 2020).

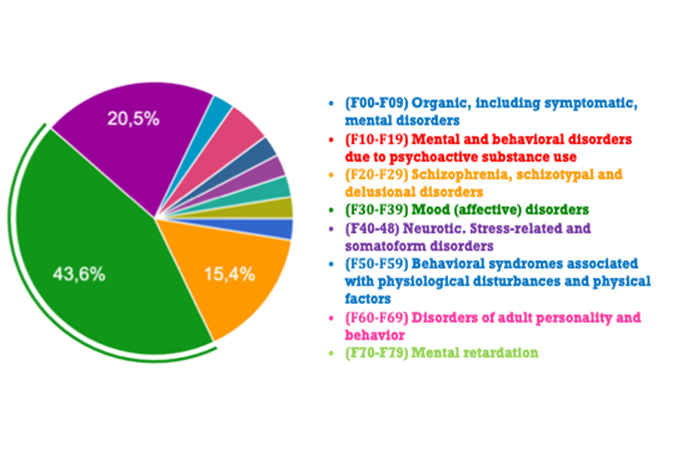

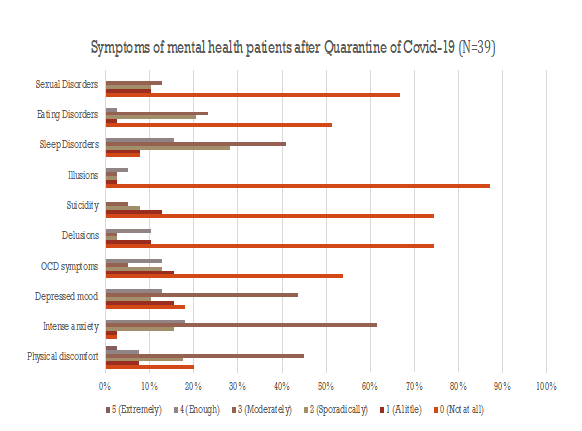

As psychologists at the community clinical level, Ms. Iliana Fylla (psychiatrist, scientific director of the Mobile Mental Health Unit of Child and Adolescent Center, KMPSY, on the island of Chios, Greece) and I studied the consequences of COVID-19 on the psychopathology of our patients after the lockdown that was enforced from March to May 2020. Our studies documented the worsening of mental health among a sample of 450 patients of KMPSY. Thirty-nine of the patients claimed to have experienced a worsening of their mental health after the pandemic. Figures 1 and 2 below illustrate these findings. This study was published at the 28th Panhellenic Psychiatric Conference held in Thessaloniki, Greece, from October 29 to November 1, 2020.

Figure 1. Mental Health Disorders (ICD-10)[1]

Figure 2. Symptomatology after Covid-19 (ICD-10)

More specifically, Figure 1 shows the percentage of the symptoms of mental health patients that were claimed to have worsened. Among all our psychiatric patients (total patients: 450), 39 patients presented a worsening of psychopathology. Figure 2 shows in detail the degrees of worsening of mental health symptoms after lockdown. Thirty-nine of 450 psychiatric patients seemed to have more illusions, delusions, suicidal thought, sexual disorders, and so forth.

In sum, the results of our study confirmed the findings of other studies and showed that 11.5% of mental health patients at KMPSY presented recrudescence in their psychopathology (79.0% women, 20.5% men).

Reviews have shown that this pandemic has been compared to natural disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis, wars, and international mass conflicts, but in these situations the threat is recognized easily, whereas in pandemic the threat is invisible, could be anywhere, and could be transmitted from any person nearby (Gorwood and Fiorillo 2020). The pandemic has created many problems. In this study patients with “affective disorders” presented more intense symptoms. Some of them also had suicidal ideation, increase of compulsions, illusions, and delusion. The best way to confront these consequences is to reinforce and enhance the care support network.

Actions for Public Mental Health

In April 2020 the Psychology Association of Chios took a series of actions to raise awareness in the local community about COVID-19 and foster and reinforce the mental health of people with useful tips and advice. As part of these actions, we gave an interview on local television (https://bit.ly/3519HHl), in which we talked about the psychological impact of the pandemic on young and older people. Understandably, people experience negative feelings such as anger, despair, and depressive symptoms that are caused by the lockdown (April–May 2020). Lockdown affects not only mental health patients but also people who have not had mental health issues before. We tried to propose constructive ways of better managing the situation.

After that, we created a small video (https://bit.ly/3evzCtH ) as an advertisement with a social message—“Keep the coronavirus away and be safe”—in which each psychologist expressed feelings and emotions about COVID-19. Finally, we published articles with tips on how to confront the situation. This multifaceted approach helped people in the local community to stay positive, reduce stress, and avoid panic. I believe that such organized action from professional and scientific organizations can effectively help people confront the situation and the impact of COVID-19.

Useful Tips

To Sum Up

This undoubtedly is a difficult and challenging period, but we can find ways to adapt and be happier living through it, even though there are radical changes in our daily life. It is crucial to focus on the present, in the “here and now,” and to the things that we can control. It is a period that shall pass and may present a good chance for all of us to treasure those little things in our lives, the most precious, which sometimes we take for granted or ignore altogether.

Let’s hope we will get through it soon.

Be strong and take care!

References

Coogan, A.N., F. Faltraco, M. Fischer, and J. Thome. 2020. “COVID-19 Paranoia in a Patient Suffering from Schizophrenic Psychosis: A Case Report.” Psychiatry Research 288 (11).

Fiorilo, A. and P. Gorwood. 2020. “The Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Implications for Clinical Practice.” European Psychiatry 63 (1), e32: 1–2.

Gunnell, D., E. Arensman, K. Hawton, and L. Appleby. 2020. “Suicide Risk and Prevention during the COVID-19 {andemic.” The Lancet Psychiatry 7 (6).

Hoffart, A., S. U. Johnson, and O. V. Ebrahimi. 2020. “Loneliness and Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk Factors and Associations with Psychopathology.” Retrieved from psyarxiv.com/j9e4q. DOI: 10.31234/osf.io/j9e4q

Shuja, K.H., M. Aqeel, A. Jaffar, and A. Ahmed. 2020. “COVID-19 Pandemic and Impending Global Mental Health Implications.” Psychiatria Danubina 32 (1): 32–35.

[1] ICD-10 is the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), a medical classification list by the World Health Organization (WHO).

December 16, 2020

The Sylff Association secretariat organized an online ceremony to confirm new fellows in China and hear presentations by one representative each from the 10 Sylff institutions in the country. The institutions are Fudan, Jilin, Lanzhou, Nanjing, Peking, Chongqing, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Yunnan, and Sun Yat-sen Universities. Reports were also made by board and steering committee members.

Among the guests invited to the meeting were newly appointed General Secretary of China Education Association for International Exchange (CEAIE) Wang Yongli and other association members. The CEAIE works with the Sylff Association secretariat to help the 10 Chinese Sylff institutions implement and improve the Sylff program at each institution.

An online meeting of Sylff Association members in China and Tokyo.

Chairman Yohei Sasakawa of the Sylff Association and The Nippon Foundation thanked the universities in his opening remarks for soundly and prudently implementing the Sylff program since its launch in China in 1992 (at the first five universities above) and 1994 (at the other five). Noting the country’s tremendous growth over the past three decades, he emphasized the need to update the Sylff program to match the current state of China’s society and economy, calling for the generous provision of fellowship to a few, exceptional students, rather than smaller stipends to a large number of fellows.

Chairman Sasakawa making his opening remarks.

Wang Yongli concurred, saying that the CEAIE will cooperate with the 10 institutions toward the goal of making the Sylff program in China more selective.

Mari Suzuki, a member of the Sylff Association secretariat and Executive Director of the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research, encouraged Sylff fellows to participate actively in the global Sylff community by taking full advantage of the support programs and networking initiatives offered by the secretariat.

A presentation by General Secretary Wang.

Representatives from the 10 institutions then explained their selection procedures and results for 2020, with all institutions confirming that the process was competitive, fair, open, and rigid. This was followed by presentations by one Sylff fellow each from the 10 universities. They detailed their academic and social engagement achievements to date and vowed to make a contribution to society in the future.

The fellows were all outstanding students, many of them being recipients of governmental and other global fellowships. The Nanjing fellow was a poet and read one of his works during the meeting. And the fellow from Sun Yat-sen related an episode of having worked as a volunteer at a Hansen’s disease facility. Others echoed Sylff’s founding concept of regarding the world as one family, with all of humankind being brothers and sisters, and of taking the initiative to promote international understanding and world peace.

The ceremony will continue to be held annually to strengthen ties among all stakeholders involved in the operation of the Sylff program in China.

“See you next year!”

November 26, 2020

The Sylff Association secretariat hosted its first virtual Sylff fellows’ meetings on October 27 and November 6 (Japan time) with the participation of fellows who received COVID-19 relief this summer. The meetings were an opportunity for pre-registered participants from around the world to get together online and share their experiences.

Group photo on October 27.

Group photo on November 6.

With the facilitation of secretariat members, fellows described how they are coping with the difficulties and challenges caused by the outbreak of COVID-19 and exchanged views on what new measures would facilitate their academic research and leaderships development initiatives during the pandemic.

Many participants commented that COVID-19 relief was a source of both financial and moral support that promoted a sense of belonging to the Sylff community. They had been concerned about disruptions to their research, with many being forced to change their data collection methods. Suggestions for additional Sylff support included new sources of research funding, mentorship and networking opportunities among current and graduated fellows, and theme-based virtual meetings.

The meeting “was perfectly organized and managed . . . so that we could express ourselves,” one fellow said on the feedback sheet. “The atmosphere was safe, welcoming and engaging. I met the Sylff fellows from all around the world and could share my research topic and exchange our views. I realized that I was not alone in this delicate situation of pandemic and that we can all together search for solutions.”

“I would most certainly recommend this kind of meeting because they help build a strong community of fellows,” another said. “Fruitful dialogue can lead to great ideas that bring positive changes to this world.”

The secretariat, too, was happy to meet the fellows online and to hear their views directly. We are currently reexamining our support programs in order to better respond to their needs under the pandemic. Please look for announcements of future events and new Sylff initiatives on the Sylff website.

November 24, 2020

By 25517

How much worse will things get in our education system? Teachers are familiar with the effects of extended periods of downtime, like that during the Covid-19 lockdown. The longer children are out of school, the more difficult it is to get them back into the routine and into the headspace needed for learning.

I have some good news and, unfortunately, some bad news too. Which would you like to hear first? Most people want the bad news first so that they can move on to the good news and end on a high. And this is the formula I will use. The bad news is, unfortunately, very bad: Take cover! Tsunami warning for the SA education system! Get ready for waves of poorly educated children exiting the education system over the next decade or longer.

But how much worse could things really get in the education sector? Have we not already reached rock bottom? No, I suspect that we still have some way to go. One of the unintended consequences of the Covid-19 lockdown in South Africa has been to push our already ailing education system to an unprecedented low.

“Children are not the face of this pandemic. But they are at risk of being among its biggest victims… in some cases, by mitigation measures that may inadvertently do more harm than good. The harmful effects of this pandemic will not be distributed equally; they are expected to be most damaging for children in the poorest countries, in the poorest neighbourhoods, and for those in already disadvantaged or vulnerable situations.” – United Nations Policy Brief, 15 April 2020.

Covid-19 will naturally affect those who are the most disadvantaged to the greatest extent. This is also true in the field of education. The renowned psychologist Edward Thorndike’s “Law of Learning” provides further support for this. It states that the more one learns, the more learning one can achieve in the future. Learning generates further interest in learning.

In fact, at a biological level we know that being exposed to interesting ideas and being curious triggers the human body’s narcotic-like dopamine chemicals to flood the brain, a positive stimulus that guarantees the individual would want to recreate these experiences.

Conversely, one who has not been exposed to learning opportunities would be less inclined to seek out cognitive stimulation. Thus, children who are described as educationally disadvantaged and were physically locked out of the education system and left to their own devices during the Covid-19 crisis are at much greater risk of not making adequate school progress in the future.

What do we know about the effects of extended periods of downtime on children’s learning? Teachers are very familiar with such scenarios as they often see a tailing off of children’s learning after long holidays and even long weekends. The longer children are out of school, the more difficult it seems to be to get them back into the routine and into the headspace needed for learning.

Teachers at the training working with the BCP materials.

In these situations, teachers constantly have to revert back to previously taught content. These learning setbacks might not be permanent, but they impact future learning.

Human cognitive development is a complex and individual process. How do we start to intervene in it?

The good news is that we have accumulated a lot of knowledge about this process and that cognitive science does have a fairly good grasp of the fundamental principles that guide effective teaching and learning.

Most importantly, we know that human beings are cognitively modifiable, thanks to the pioneering and extraordinary work of the late cognitive psychologist Professor Reuven Feuerstein. The implications of this seemingly unassuming statement are profound for educators and for children not already in the learning loop. The notion of cognitive modifiability gives substance to the cliché that “all children can learn”. For too long we have been dominated by a deterministic, all-or-nothing view of human cognition; either you have the “smarts” or you don’t.

Children who are working with the BCP materials.

This recognition of cognitive modifiability has resulted in the development of cognitive intervention programmes, such as Instrumental Enrichment, Bright Start and Basic Concepts Programme. While traditional curative (remedial) programmes aim to close gaps in content learning, cognitive programmes aim to promote the growth of cognitive structures that are needed for higher order and abstract reasoning.

But is it possible to enhance the development of cognitive processes inside the classroom and can teachers do this? It is our experience that emergent cognitive structures can be enhanced and teachers can be trained to become mediators of learning. Mediated learning differs vastly from traditional “chalk-and-talk” pedagogical approaches on both a philosophical as well as humanistic level.

Human mediators are caring, engaged, open, interactive and intensively involved with their children in the classroom. Young children happen to need these kinds of engagements to free up their involvement and participation. Children who take risks and share their thinking and are able to express their ideas are set on a path to improve their thinking, to reflect on it and consider the views of others.

So why are such cognitive educational approaches not being used more in learning institutions, particularly for young children who are not already engaged in learning and might have cognitive vulnerabilities?

Children who are busy with an activity related to the programme

The Basic Concepts Programme is being extended across Grade R classes throughout the Northern Cape. The Northern Cape Department of Education has been forward-looking in helping to establish solid cognitive foundations needed for enhanced learning. There is an understanding that cognitive development and the school curriculum are not mutually exclusive activities, but both are integral. In a pilot study we have found almost universal improvements in school readiness of children who have been exposed to this cognitive programme during their school day.

The disruptions to teaching and learning in these very unsettled Covid-19 times might, in fact, allow those invested in education to pause, take stock and re-evaluate our understanding and approaches.

How does our practice as educators align with what we know about learning from cognitive science, and are we following the best evidence-based practices that will help children to improve their learning? It might be that the unintended outcome of the crisis also mobilises those involved in education to develop a range of special interventions to re-establish an interest in learning.

All children can learn and make educational progress, but it might be that some children need a more thoughtful, intentional and mediational approach to successfully re-enter the educational mainstream.

This article acknowledges the Douglas Murray Trust and Ryoichi Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship Fund for their generous support of the work done by the author with the Northern Cape Department of Education.

* * *

Reprinted, with a lead by the author, from DAILY MAVERICK which is one of the largest and most credible online newspapers in South Africa; https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-11-02-the-state-of-south-african-education-covid-19-implosion-brings-good-news-and-bad-news/.

November 16, 2020

The Sylff Association secretariat is happy to report that over 30 members of the Sylff community donated a total of 1,366,400 yen (approximately US$13,000) to support Sylff fellows affected by COVID-19. Thank you all for giving so generously. The online fundraising system to accept donations via credit card is now closed.

The donations are being used to help defray fellows’ living expenses and encourage them to continue their studies and research at their home Sylff institutions despite the difficulties caused by the pandemic.

COVID-19 has seriously disrupted the research activities of many Sylff fellows and could affect their chances of emerging as future leaders. The support offered by the Sylff community not only helped finance their studies but, as reported by several fellows, gave them a sense of hope and belonging.

Once again, we would like to express our heartfelt thanks to everyone who made a contribution to COVID-19 Relief for Sylff Fellows.

October 22, 2020

The Sylff Association secretariat is seeking submissions of articles about COVID-19 to be published in the “Voices from the Sylff Community” section of the Sylff website. We hope to showcase the insights and activities of Sylff fellows related to the global pandemic and its social impact, the sharing of which may help others to better cope with the difficult circumstances. The articles will also be published in e-book form in 2021.

Articles should describe your insights, analyses, or activities related to the novel coronavirus. They can be written from either a professional or personal point of view. We will accept articles that have been printed in other media.

Two COVID-related articles have already posted on the Sylff website:

“Providing Space for Good Conversations on YouTube amid the COVID-19 Pandemic” by James Martyn

“What COVID-19 Can Teach Us about Prison: Reflections on Criminal Policy and the Words of Albert Camus” by Rui Caria

Submission Guidelines

Length: Approximately 1,500 words (may be longer depending on content)

Quotes: Please cite sources if you include quotes

Photos: Digital photos to go with the article are encouraged but not mandatory

Deadline: February 28, 2021

Submission: Send your article to sylff@tkfd.or.jp. The email subject line should include “VOICES COVID-19”

We are looking forward to receiving your “Voice” about the pandemic.

October 16, 2020

By 27510

This article reflects on the role of “WhatsAppers”, defined as social activists appropriating WhatsApp as a primary platform to organize and communicate, in relation with the rise of Bolsonarism in Brazil. Affordances of WhatsApp usage by social actors are explored in the light of responses to Bolsonarism, along with their implications in the current time of crisis.

* * *

Photo credits: Lo Cole / The Economist

The research illustrated explores the affordances of WhatsApp and its appropriation by the WhatsAppers in Brazil, here defined as social activists appropriating WhatsApp as a primary platform to organize and communicate. I explore the importance of the Global South context in shaping such affordances, focusing on local epistemologies which bypass the structure of mainstream Brazilian media. As illustrated elsewhere, the empirical analysis combined different qualitative methods, yielding insights into the communication and action repertoire of the group studied, not without considering reflections on research ethics and their implications in the context studied.

WhatsAppers: Towards a new research agenda

This research stems from an analysis of the social interactions of UnidosContraOGolpe (UCG), a leftist group in Brazil, which was a WhatsApp “private group” emerged in 2016 to oppose the controversial impeachment of the then-president Dilma Rousseff. The case study resulted into the first empirical MA dissertation in Latin America to explore digital activism on WhatsApp private chats as an emerging field of political action. To do so, a ‘meso-micro’ analysis was used – on the meso level, to identify the modus operandi of group interactions and, on the micro level, to capture individual motivations, tensions, and expectations. At the core of the investigation, the researcher’s identity was disclosed, following social actors through their chat environment and adopting an ‘engaged’ approach, whereby the research is designed with the goal of empowering social actors. In practical terms, this inspired a triangulation of qualitative methods, including digital ethnography (to identify and analyze the practice of social actors inside the chat domain, through a long “zoom” perspective on social interactions in the private chat group), content analysis of selected posts (to understand how the group emerged organically and self-organized in a contingent manner) and fifteen in-depth semi-structured interviews (to elicit values and motivations from the perspective of individual active participants).

This dissertation argues that WhatsAppers are characterized by their ability to appropriate the chat group as a means to participate in political life. Engagement with political activism becomes an intimate and familiar affair, mediated by a personal and omnipresent device, that enables a unique approach to mobilization. In general lines, everyone could be a WhatsApper, including those not previously politically active. A WhatsApper could be someone who already is entwined in other social media networks of politics and mobilization or not; they can be someone from a poor, middle or rich class background. In other words, WhatsAppers interact digitally with others, combining online and offline political actions. Through the lens of digital sociology, the case studied reveals that WhatsApp stands out as a platform for civic engagement, promoting new spaces of digital activism for three main reasons: the chat app (1) affords structurally new forms of political participation and collective engagement, (2) forges communities of mutual interest, and (3) promotes collective decision-making and individual autonomous actions on a small scale. However, drawbacks are found in howbots can influence conversations on WhatsApp, fake users can hijack chats, and group members may be threatened by surveillance attacks.

Bolsonarism: into the Brazilian political crisis

In 2019, the first year of Jair Bolsonaro’s government, Brazil has seen a record deforestation and a drop to zero applications of environmental fines. Bolsonaro nominated a human rights minister who was well-known for preaching sexual abstinence as a state policy. Sons of the president are under investigation of crime and corruption. Also, Bolsonaro has nominated a secretary of culture extolling Nazi propaganda. Moreover, every week the Brazilian “anti-president” openly attacks the press, and recently was considered the worst leader to struggle against the Coronavirus pandemic.

The political scenario in which Bolsonarism surges is widely recognized as reflecting a crisis of political representation and the widespread disbelief in politics and traditional parties. Bolsonarism can be understood as “a political phenomenon that transcends the figure of Bolsonaro and is characterized by an ultra-conservative worldview, returning to traditional values and nationalist and patriotic rhetoric”. Facing this scenario, an urgent question should be addressed: what is really happening to Brazilian democracy?

Looking back, looking forward

Brazil is an extremely unequal country along multiple dimensions that include internet access. Part of the semi-illiterate population gathers their information almost solely through visual messages, audios and videos from thousands of WhatsApp groups, thanks to the “zero rating” fees provided by telecom companies that replaced more expensive short-text messages. The larger context of Latin America makes an excellent test bed for the study of WhatsApp social interactions because “96 percent of Brazilians with access to a smartphone use WhatsApp as primary method of interpersonal communication”. According to the Reuters Institute, 53 percent of Brazilians use “ZapZap” (as the app is commonly known in the country) to find and consume news. Everyday citizens also use “ZapZap” to order pizza, stay in touch with family, transfer money, make doctor appointments, learn, spread gossip and date.

While the leftist “UCG” WhatsAppers were calling for political action, far right activists were articulating themselves in WhatsApp private groups and beyond, also combining online and offline activities. Progressive sectors were as well unable to build a national digital campaign, with very rare exceptions, such as small local initiatives like UCG. Consequently, the potential of digital activism on chat apps was later weaponized by far-right groups that not only appropriated public and private groups on and with WhatsApp, but also acted as pipeline to other social media. Digital information became a “weapon” that is still used in “out of control” mode nowadays by Bolsonaro’s supporters, taking advantage of the high penetration of WhatsApp in Brazil, and facilitated by the limited digital literacy of the population. In fact, Bolsonaro ran a successful campaign in 2018 based on a combination of bottom-up authoritarianism and digital populism. His supporters were helped by bots to spread misleading content “weaponizing” various WhatsApp groups.

COVID-19: creative WhatsAppers from the margins

This case presents important implications for the ongoing crisis. Brazilian citizens are currently bombarded with COVID-19 related disinformation and facing a chaotic portrait, while far right activists occupied larges spaces on digital networks before and after the 2018 elections. Moreover, there are lessons learned from the inability to stop Bolsonarism’s digital army, namely: send messages which everyday citizens can trust. Today, Brazilians behave more and more like consumers instead of citizens, trusting the market more than science – perhaps this is precisely the gap that paves our country for thousands of deaths during the coronavirus pandemic.

Brazilian mainstream media are currently discussing who might be a potential presidential candidate for the next elections in 2022. However, a deeper question is whether democratic values will still be upheld at that time. The composition of Bolsonaro’s government reminds us that Brazilian’s young democracy is now more capitalist, colonialist, patriarchaland is heading towards a dangerous and irresponsible political adventure, and the outcomes are unpredictable. During the pandemic, social distancing, hand washing, hand sanitizers, masks, respirator machines and lockdowns are privileges of the Global North, while in the South, many will not even have access to minimum services.

As the title suggests, using WhatsApp for chatting and hanging out alone will not solve the political Brazilian disarray, but perhaps creative WhatsAppers could provide a spark to create national-transnational solidarity. Namely: high speed participatory decision-making to deliver groceries, collect money, produce masks, share scientific information, mobilize against COVID-19 related disinformation, reach poor families and fight for emergent democratic imaginaries. The UCG case study still works as a well-informed internal communication strategy for connecting and activating social solidarity networks that grounds for hope, especially because it reveals the battlefield of political struggle that enables scientific shared information, civic engagement, collective mobilization, and solidarity. Lastly, the coordination of online activities combined with actions on the ground by WhatsAppers triggers digital activism in times of pandemic.

About the author

Sérgio Barbosa

Sérgio Barbosa is a PhD candidate in the program “Democracy in the Twenty-First Century” in the Centre for Social Studies (CES), at the University of Coimbra and a Sylff fellow sponsored by Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research. He is a member of the Technopolitics – a “Latin” research network connecting Brazil and Ecuador with Spain, Portugal and Italy. His research explores the emerging forms of political participation vis-à-vis the possibilities afforded by chat apps, with emphasis on WhatsApp for digital activism and social mobilization

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Silvia Masiero for her careful review (and beyond) and wishes to thank Charlotth Back and Jeroen de Vos for their comments and suggestions. He extends his gratitude also to Stefania Milan and Emiliano Treré for launching Big Data from the South initiative. This blogpost has received funding from the Sylff (Ryoichi Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship Fund) Research Abroad – SRA fellowship sponsored by the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research.

Reprinted, with a lead by the author, from DATACTIVE Big Data Sur blog, https://data-activism.net/2020/06/bigdatasur-whatsapper-ing-alone-will-not-save-brazilian-political-disarray-an-investigation-of-the-affordances-of-whatsapp-under-bolsonarism/.