How did medical authority shape motherhood in twentieth-century Hungary? Fanni Svégel (Eötvös Loránd University, 2025) explores the rise of “scientific motherhood,” tracing how expert-driven childcare practices redefined maternal roles and reinforced gendered expectations through state policy.

* * *

My brother Pali’s development was recorded in a diary, a large squared notebook, with special attention devoted to his movements. He was left unbound, free to kick without swaddling—something I later learned had also been done with me. By now it is clear that they [the parents] were followers of Emmi Pikler’s method of infant care.[1]

Péter Nádas, an internationally renowned contemporary Hungarian writer, recalled in his novel how such practices were common among the Budapest middle class in the 1940s. His personal memory reflects a broader trend: the professionalization of child-rearing and motherhood in mid-twentieth-century Hungary. What had once been a marginal practice of the interwar elite—keeping detailed records of a newborn and encouraging free movement and exploration—became widespread under state socialism, due in part to Emmi Pikler’s influential childcare manuals. This model of “scientific motherhood” established a medicalized framework of childcare that helped define the ideal of “righteous motherhood.”[2]

This article examines how medical knowledge production influenced the normative concept of the good mother in twentieth-century Hungary, turning previously marginal practices into mainstream norms. It also examines how family mainstreaming came to place primary responsibility for care work on women, tracing the historical roots of “righteous motherhood” at the intersection of state population policy and medicalization.

Family Mainstreaming and the Rise of Medical Authority

In recent years, Hungary has taken a prominent role globally as an initiator of international treaties and conferences aimed at reframing human rights and serves as a laboratory for “family mainstreaming.” In these “pro-family” narratives, child welfare becomes a powerful rhetorical tool justifying the illiberal government’s actions.[3] But what are the historical roots of family mainstreaming, and why has the prioritization of the family often come at the expense of gender equality?

State population policy is closely intertwined with dominant narratives of motherhood. Cross-regime examinations of twentieth-century family policy reveal the continuity of expectations placed on women as primary caregivers. Hungary has a long history of state-provided maternal benefits, and from 1967 onward, working mothers were allowed to stay at home with their babies for up to three years. The childcare allowance—which is still offered today—reinforced traditional gender roles, placing a double burden on women as both workers and caregivers.[4] At the same time, the concept of appropriate care work evolved under the influence of medicalization.

The pediatric ward at the National Social Security Institute (OTI), Áruház Square, Csepel, 1949. ©Fortepan / Kovács Márton Ernő

The construction of expert knowledge in child-rearing intersects with medical knowledge production and the prevailing power structures. This framework assumes that knowledge originates from trained professionals, interpreting it as reliable and scientific. In contrast, the concept of authoritative knowledge is more permissive regarding the source of knowledge, acknowledging the agency of laypeople in shaping childcare practices.[5]

This raises the question: who owns knowledge? At the beginning of the twentieth century, the image of the good mother became increasingly tied to expertise, as child welfare and caregiving professions evolved, opening space for women as professionals in medical environments.

These women—midwives, nurses, and physicians—occupied intermediate positions within the power hierarchy, bridging the state and ordinary people. These lower-level agents, with varying degrees of autonomy, helped shape the notion of expertise.[6] Consequently, the twentieth century marked the first time in modern history that women could emerge as authorities on matters concerning the female body, influencing both public and private reproductive discourse. This professionalization tendency was caught between inherited knowledge, folk medicine, customs, and highly medical approaches.[7]

The differences in types of knowledge lead to a second question: what is the source of knowledge? With professionalization, knowledge about pregnancy, childbirth, child-rearing, and intimacy moved beyond the personal spheres of family, kinship, and friendship, and books became a central medium for its transmission. This shift signaled modernization, generating tensions as it distanced individuals from the knowledge and customs of previous generations. The consolidation of medical authority, alongside the widespread distribution of books, transformed women’s relationships with their bodies. On one hand, they became more vulnerable within healthcare institutions; on the other, they gained access to more reliable information about pregnancy, childbirth, and infant care.

Emmi Pikler and the Scientific Turn in Childcare

In the twentieth century, child-rearing was transformed into a scientific enterprise, managed by experts. Among them was Emmi Pikler (1902–1984), a pioneering pediatrician whose work in postwar Hungary reshaped infant care under socialism and beyond. As a physician and childcare specialist, Pikler played a significant role in developing infant care practices and institutions in the post–World War II era. Of Austro-Hungarian Jewish origin, Pikler was connected to interwar reform education and left-wing intellectual circles. Upon receiving her medical diploma in Vienna, Pikler returned to Hungary and opened a private practice in Budapest. After World War II, she was appointed director of the Lóczy Residential Infant Home—an institution built on socialist state ideals—where she developed her distinctive caregiving model.[8]

Pikler’s first book, What Does the Baby Already Know?, was published in 1940, providing advice for young mothers on early development. Her second childcare manual, Mothers’ Book, was first published in 1956 and reissued several times until 1985, thus spanning almost the entire socialist period. Based on the narrative analysis of these volumes, this article examines two debated aspects of her method: the “cry-it-out” approach and scheduled breastfeeding.

What Does the Baby Already Know? devoted particular attention to what Pikler termed “raising children to cry,” by which she referred to the tendency of inexperienced parents—especially mothers—to respond to an infant’s crying with immediate soothing, rocking, or holding. In her view, such practices unintentionally conditioned children to cry more often and therefore represented an inadequate way of addressing infant behavior.

She argued that infants who were allowed to cry until about six months of age later developed greater autonomy and problem-solving abilities. During this early stage, Pikler regarded caretaking practices such as prolonged holding or “unwarranted” rocking—unless driven by a physical need—as a form of spoiling. Her position on crying was not exceptional in its time but rather aligned with prevailing conceptions of the child as an individual requiring discipline and order.[9]

An infant home in Stalin-City, 1959. ©Fortepan / Peti Péter

Maternal Love versus Caregiving Skills

In Mothers’ Book, Pikler distinguished maternal love from caregiving, framing the latter as a skill to be learned rather than an instinct directly tied to affection. She argued that the consistent presence of a primary caregiver—ideally the mother—was most beneficial for the infant, enabling the formation of a secure and intimate bond. She emphasized regularity and precision in routines of feeding, bathing, and sleeping, thereby promoting a stable and predictable daily rhythm for the child.[10] Although, from the late 1940s, Pikler served as the head of a residential infant home for children who lacked family care, her manual was directed at parents rather than institutional caregivers.

The second debated issue in Pikler’s book concerned scheduled breastfeeding. From the early twentieth century onward, medical literature recommended feeding infants five to six times a day at three-hour intervals—a practice justified by concerns for health preservation and hygiene.[11] In this framework, the physician decided what was beneficial for the child’s well-being, and the “good mother” was one who followed medical instructions. Mothers’ Book also placed particular emphasis on the necessity of medical supervision. In the 1963 edition, scheduled feeding (every three hours) was still recommended; by the 1980s, however, revised editions advocated feeding on demand, thereby aligning with the prevailing scientific consensus.[12] In Pikler’s view, infants were calmer within a stable and predictable routine.

In both books, motherhood was framed as a learnable ability grounded in expert knowledge, explicitly distancing care from instinct or “natural” affection. Drawing on the concept of “rational love,” What Does the Baby Already Know? advanced the view that learning proper caregiving was the mother’s duty, since only through such acquired competence could an infant’s needs be adequately recognized and met.

Caring labor was conceived as both an integral aspect of motherhood and a learnable process, regarded as essential for the construction of socialist society. Emmi Pikler thus sought to institutionalize a new, medically informed model of child-rearing, in which maternal competence was subordinated to the authority of medical expertise. In doing so, she built on the historical legacy of maternalist policies that linked caregiving to motherhood, while simultaneously promoting a professionalized form of caregiving.

[1] Péter Nádas, Világló részletek I (Budapest: Jelenkor, 2017).

[2] Risa Cromer and Lea Taragin-Zeller, “Reproductive Righteousness of Right-Wing Movements: Global Feminist Perspectives,” Women's Studies International Forum 105 (2024): 102947, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2024.102947.

[3] Andrea Pető and Borbála Juhász, “Legacies and Recipe of Constructing Successful Righteous Motherhood Policies: The Case of Hungary,” Women's Studies International Forum 103 (2024), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277539524000232.

[4] Éva Fodor, The Gender Regime of Anti-Liberal Hungary (Palgrave Pivot, 2020).

[5] Brigitte Jordan, “Authoritative Knowledge and Its Construction,” in Childbirth and Authoritative Knowledge: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, eds. Robbie E. Davis-Floyd and Carolyn Fishel Sargent (University of California Press, 1997), 55–79.

[6] Zita Deáky and Lilla Krász, “Lészen az Istennek áldásábúl magzattyok…” Születés és anyaság a régi Magyarországon, 16. század – 20. század eleje (Budapest: Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont Történettudományi Intézet, 2024).

[7] Fanni Svégel, “The Role of Women as Agents and Beneficiaries in the Hungarian Family Planning System (1914–1944),” Journal of Family History 48, no. 3 (2023): 338–353, https://doi.org/10.1177/03631990231160222.

[8] Fanni Svégel, “Anyaság és gyereknevelés a professzionalizáció és a politika szorításában: Pikler Emmi munkássága,” Opuscula Theologica Et Scientifica 3, no. 1 (2025): 231–260, https://doi.org/10.59531/ots.2025.3.1.231-260.

[9] Emmi Pikler, Mit tud már a baba? (Budapest: Medicina Könyvkiadó, 1959), 9–13.

[10] Magda László and Emmi Pikler, Anyák könyve (Budapest: Medicina Könyvkiadó,1963).

[11] Zsuzsa Bokor, “‘Separation Is Required in Our Special Situation’: Minority Public Health Programs in Interwar Transylvania,” Hungarian Historical Review 12, no. 3 (2023): 395–432, https://doi.org/10.38145/2023.3.395.

[12] László and Pikler, Anyák könyve.

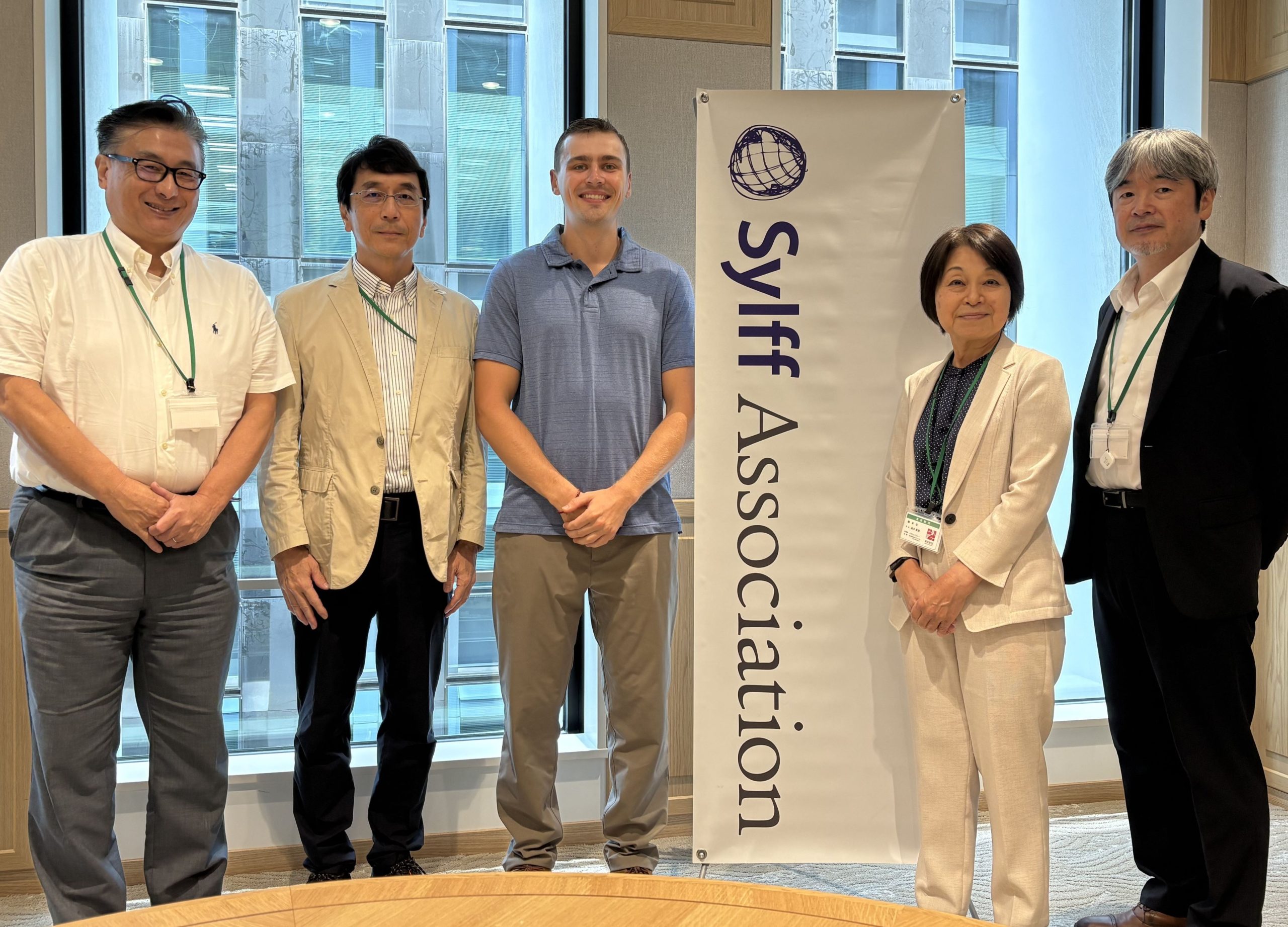

Schulz was visiting Japan to pursue a collaborative partnership with Kobe University, an outgrowth of a presentation she gave at a conference in the city last year.

Schulz was visiting Japan to pursue a collaborative partnership with Kobe University, an outgrowth of a presentation she gave at a conference in the city last year. Jennifer Schulz’s visit was a reminder of how research rooted in empathy can drive meaningful change. Her work not only advances academic understanding but also transforms lives—helping patients heal, guiding policy reform, and inspiring future generations. The Sylff Association secretariat is honored to support her work and looks forward to the continued ripple effects of her leadership. (Compiled by Nozomu Kawamoto)

Jennifer Schulz’s visit was a reminder of how research rooted in empathy can drive meaningful change. Her work not only advances academic understanding but also transforms lives—helping patients heal, guiding policy reform, and inspiring future generations. The Sylff Association secretariat is honored to support her work and looks forward to the continued ripple effects of her leadership. (Compiled by Nozomu Kawamoto)

On September 19, 2025, the Sylff Association secretariat was pleased to welcome

On September 19, 2025, the Sylff Association secretariat was pleased to welcome  The Sylff Association secretariat is proud of Dasgupta’s ongoing contributions to sustainability in India and beyond. We warmly welcome all fellows and steering committee members to visit us during their time in Tokyo. (Compiled by Nozomu Kawamoto)

The Sylff Association secretariat is proud of Dasgupta’s ongoing contributions to sustainability in India and beyond. We warmly welcome all fellows and steering committee members to visit us during their time in Tokyo. (Compiled by Nozomu Kawamoto)

On a spring afternoon in Paris, the Conservatoire’s campus in La Villette Park was filled with the energy of young musicians from around the world. Among them was

On a spring afternoon in Paris, the Conservatoire’s campus in La Villette Park was filled with the energy of young musicians from around the world. Among them was