University of Nairobi Sylff fellows organized a LANS meeting on November 29 and 30, 2019—their second meeting following a LANS gathering the previous year. Academic presentations were made by fellows on the first day, and participants visited Bethsaida Community Foundation to spend time with needy children on the second day. This report outlines the activities over the two days.

* * *

The 2019 LANS meeting of the University of Nairobi (UoN) Sylff Chapter on November 29 and 30 was held in line with the recommendations of the 2018 LANS meeting, which advocated a two-day gathering of academic presentations and a social engagement activity. Therefore, the first day featured academic presentations, while the second day entailed a visit to the Bethsaida Community Foundation. The meeting was organized by five fellows: Jacinta Mwende, Socrates Majune, Alexina Marucha, Steve Muthusi, and Awuor Ponge.

Twenty-three participants attended the meeting on the first day: 21 fellows, Aya Oyamada of the Sylff Association Secretariat, and Professor Lawrence Ikamari of the Graduate School. Fellowship years ranged from 2003–05 to 2017–19. Two fellows attended from abroad—Tanzania and Germany—while the rest were from Kenya but spread across many different cities and towns: Nairobi, Kisumu, Homa-Bay, and Mombasa. The meeting was held at the University of Nairobi Towers from 12:30 pm to 6:00 pm.

On the second day, 15 participants—Oyamada and 14 fellows—visited Bethsaida Community Foundation. The event started at 11:00 am and ended at 3:00 pm.

Group photo of LANS participants on November 29, 2019.

LANS participants outside the Bethsaida Community Foundation on November 30, 2019.

Presentations

Professor Lawrence Ikamari making his opening remarks on the first day.

The meeting was officially opened by Professor Lawrence Ikamari, Deputy Director of the UoN Graduate School. He expressed his gratitude to the Sylff Association for its generosity in sponsoring the LANS event. Aya Oyamada followed with a presentation on various Sylff Association support programs. Key among them was the new Sylff Disaster Relief Fund aimed at bringing together the resources of the Sylff community to support fellows who are engaged in immediate relief and recovery efforts following large-scale natural disasters in the vicinity of Sylff institutions. It was launched after the Mexico City earthquake of September 2017. More information about the program can be found at this link https://www.sylff.org/support_programs/sylff-disaster-relief-fund/.

Then there were eight presentations by fellows, with current fellows presenting first (master’s students), followed by current PhD fellows, and lastly fellows who have moved on to an academic or professional career. This arrangement ensured that fellows learned from one another, especially with up-and-coming scholars getting a chance to learn from their seniors.

Brenda Oloo responding to a question.

The first presenter was Brenda Oloo, who holds a bachelor of arts, first class honours (FCH), from UoN with majors in sociology and political science and public administration. She graduated on December 20, 2019, with a master of arts in sociology, receiving a Sylff fellowship between 2017 and 2019. Her presentation, based on her master’s thesis, examined several issues of male infertility in Machakos County, Kenya, and offered policy recommendations for the Ministry of Health in Kenya.

Jacob Omolo.

Jacob Omolo, the second presenter, dropped out of high school due to poverty but enrolled in UoN in 2012 and graduated in 2016. With Sylff’s support, he began studying for a master of education in educational planning in September 2017. He presented a proposal on the influence of adherence to the Commission for University Education (CUE) guidelines on provision of quality education. Omolo seeks to assess the CUE guidelines on physical facilities, assessment of academic programs, the employment of teaching staff, and library resources. He currently teaches at Ahono Tumaini School in Siaya County, Kenya.

Miriam Viluti.

Miriam Viluti holds a bachelor of education arts in business studies and geography and a master of education in education economics, both from UoN, and received a Sylff fellowship in 2017–19. Her presentation was on the influence of socioeconomic factors on pupils’ transition rate to secondary schools in Kibra sub-county, Nairobi. In order to enhance transition rates, Viluti recommended standardizing the hidden costs of education at the basic level; initiating, monitoring, and evaluating empowerment policies to improve living standards; and encouraging collaborative multidisciplinary research. She is currently an employee of the UoN Graduate School and is working toward starting her PhD studies.

Sennane Riungu.

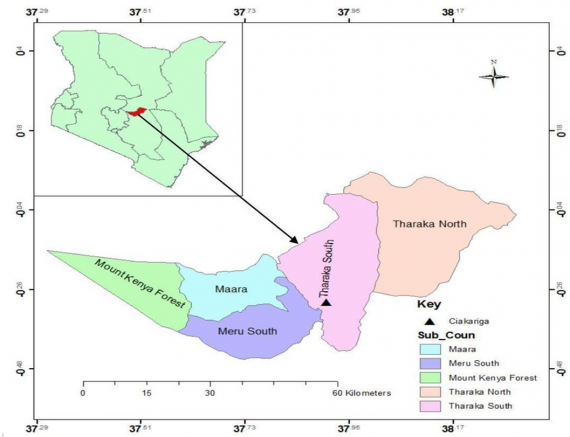

Sennane Riungu was a fellow between 2006 and 2008 and is currently a PhD student in international studies at the Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies, UoN. She was awarded an SLI in 2013 and 2019, and her presentation was based on the 2019 SLI award on the “Greenhouse Enterprise.” This agribusiness project is based in Maara constituency, Tharaka-Nithi County, and encourages efficient and economically beneficial agricultural practices. Through this project, Riungu hopes to empower society, especially members of the Makuri Development Forum, by equipping them with agricultural business enterprises skills. More information is available at: https://www.sylff.org/news_voices/26460/. Riungu is currently a visa processing officer for the Australian High Commission in Nairobi.

Henry Bosco.

Henry Bosco is a journalist by profession who currently works at Maseno University and Laikipia University as a lecturer in the Media and Communications Department. He is also pursuing a PhD in communication and information studies at UoN and holds a master of arts in communication studies and bachelor of arts in journalism and media studies (FCH), both from UoN. His fellowship period was between 2012 and 2014. Bosco’s presentation assessed the binary impact of media coverage on terrorism and recommended that the media play a bigger role in countering terrorism by framing the actions in a less fear-provoking manner.

Jackie Okelo.

Jackie Okelo is a lecturer in the Department of Linguistics at Maseno University and is currently pursuing a PhD in linguistics at the university, having obtained a bachelor of education (arts) and master of arts in linguistics from UoN. She was a fellow between 2006 and 2008. Her presentation was on the “bedroom metaphor,” as presented in the political discourse surrounding the November 2019 Kibra by-elections in Kenya.

Jeremy Muthoka (next to the board) and Dominic Amoro engage in a psychological game during Muthusi’s presentation.

Steve Muthusi, the seventh presenter, is currently a DAAD scholar at the Institut für Psychologie, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, pursuing a PhD in cognitive and biopsychology. Prior to this, he graduated with a degree in social sciences with majors in psychology and sociology (FCH) and a master of psychology (sponsored by Sylff), both from UoN. He is a personal and professional development author, speaker, and trainer. He is the author of a book titled Stir Up Your Potential, and his presentation was on how stress affects the behavior of individuals (executive functions).

Socrates Majune introducing the project.

The last presentation was by Socrates Majune, who is the current chairperson of the Sylff UoN Chapter. He is an economist and is currently pursuing a PhD in economics from UoN. His holds a bachelor of economics and statistics (FCH) and a master of art in economics, both from UoN. He was a fellow between 2013 and 2015. His presentation was on his collaborative research with Eliud Moyi, a 1993–95 fellow. Moyi is an economist and currently works at the Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) as a policy analyst. Since Moyi was absent, Majune presented their paper explaining export duration in Kenya that was recently published online in the South African Journal of Economics (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/saje.12243). The research assessed reasons exporters from Kenya exit foreign markets faster than expected, and the authors recommend trade policies that can be adopted by stakeholders, such as the government of Kenya, to enhance the sustainability of Kenyan exports in foreign markets.

Visit to Bethsaida Community Foundation

Aya Oyamada introducing herself in Swahili during the introduction session.

On November 30, Aya Oyamada and 14 fellows visited the Bethsaida Community Foundation, a community-based, nongovernmental, nonprofit organization that hosts orphans and vulnerable children (OVC), such as street children. The foundation was launched in 2009, and it currently has two branches in Kenya: one in Githurai and the other in Yatta. The foundation cares for OVCs by giving them parental love, spiritual care, and rehabilitation, as well as formal education to promote their personal and professional growth.

Mr. Kamau, founder of the Bethsaida Foundation, introduces himself.

The main events of the day involved donating food, clothing, stationary, and eating lunch with the kids. Fellows raised Kshs. 34,600 (US$346), which was used to buy stationary, snacks, and food for lunch. The event also involved giving motivational talks and Christian teaching.

Fellows visited the Githurai branch.

Jacinta Mwende (left) and Jackie Okelo (right) serve children sodas and biscuits.

Jackie Ogeto serves children lunch.

Fellows and children enjoy their meal during lunchtime.

Fellows and children enjoy their meal during lunchtime.

Steve Muthusi (left), Awuor Ponge (center), and Alexina Marucha prior to their departure from the Bethsaida Foundation.

Follow-up Visit to Bethsaida Foundation

Eliud Moyi and Socrates Majune made a follow-up visit to the Bethsaida Community Foundation on December 8, 2019, primarily to make arrangements to sponsor a child with excellent academic potential that the foundation would recommend. The initial activities of this visit involved presentations by the children. Thereafter, Moyi made his presentation before meeting Mr. Kamau, founder of the Bethsaida Foundation, with Majune. Their meeting lasted for one hour. Moyi offered to sponsor one student through high school by paying school fees and providing other necessities. As of the writing of this report, Moyi had already sponsored the student for their first year of high school. Fellows also sponsored another student who joined a day-school in their first year of high school.

“Mr. Sasakawa, from Japan, for the love of humanity sponsored me through my master’s studies without knowing me directly. It is for this reason that I give back to strangers.”

——Eliud Moyi

Eliud Moyi making his presentation about the need to obey parents as per the Bible.

Conclusion and Acknowledgments

The 2019 LANS event sought to benefit fellows in two ways: enhancing their presentation skills and giving back to society. This was successfully done over the two days. In addition, the decision to sponsor a needy child by Eliud Moyi affirms that fellows are putting into practice the mission of the Sylff Association, that is, contributing to and sharing the happiness of others.

The organizers of the LANS 2019 meeting offer their immense thanks to the Sylff Association for its financial support in enabling long-distance fellows to participate. Gratitude also goes to the Graduate School of the University of Nairobi for providing a venue at the university and for endorsing our application. Lastly, the organizers appreciate the sacrifice made by all fellows who attended the meeting.

List of Participants

|

Day one (November 29)

|

|

Day two (November-30)

|

|

|

No.

|

Name

|

Fellowship year

|

Name

|

Fellowship year

|

|

1

|

Sennane Riungu

|

2006–2008

|

Desterio Murabula

|

2016–2018

|

|

2

|

Desterio Murabula

|

2016–2018

|

Sharon Mumbi Kinyanjui

|

2015–2017

|

|

3

|

Henry Kibira

|

2012–2014

|

Jackie Okello

|

2006–2008

|

|

4

|

Brenda Oloo

|

2017–2019

|

Stephen Okelo

|

2007–2009

|

|

5

|

Miriam Viluti

|

2017–2019

|

Dominic Amoro

|

2012–2014

|

|

6

|

Maxwell Muthini

|

2017–2019

|

Ouma Omito

|

2006–2008

|

|

7

|

Sharon Mumbi Kinyanjui

|

2015–2017

|

Jacob Omolo

|

2017–2019

|

|

8

|

Jackie Okello

|

2006–2008

|

Jackie Ogeto

|

2006–2008

|

|

9

|

Agnes Mutisya

|

2007–2009

|

Maxwell Muthini

|

2017–2019

|

|

10

|

Stephen Okelo

|

2007–2009

|

Jacinta Maweu Mwende

|

2004–2006

|

|

11

|

Caroline Wanjiru

|

2013–2015

|

Stephen Katembu Muthusi

|

2014–2016

|

|

12

|

Dominic Amoro

|

2012–2014

|

Marucha Alexina Nyaboke

|

2014–2016

|

|

13

|

Maryam Abubakar Swaleh

|

2009–2011

|

Cannon Awuor Ponge

|

2007–2009

|

|

14

|

Ouma Omito

|

2006–2008

|

Socrates Kraido Majune

|

2013–2015

|

|

15

|

Jacob Omolo

|

2017–2019

|

Aya Oyamada

|

Non-fellow

|

|

16

|

Jeremy Muthoka

|

2003–2005

|

|

|

|

17

|

Jacinta Maweu Mwende

|

2004–2006

|

|

|

|

18

|

Stephen Katembu Muthusi

|

2014–2016

|

|

|

|

19

|

Alexina Nyaboke Marucha

|

2014–2016

|

|

|

|

20

|

Cannon Awuor Ponge

|

2007–2009

|

|

|

|

21

|

Socrates Kraido Majune

|

2013–2015

|

|

|

|

22

|

Aya Oyamada

|

Non-fellow

|

|

|

|

23

|

Prof. Lawrence Ikamari

|

Non-fellow

|

|

|

Link to photos: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1KdbvAJLw6zyG0g8wOYkH11ByK6HBKCJg