Multicultural education that seeks to balance diversity and unity has become vital for many countries in the era of globalization. The “color-blind” approach that promotes equality regardless of race or ethnicity often overlooks systemic disparities, however. Dak Lhagyal (Columbia University, 2020, 2021) used an SRG award to explore the implementation and impact of multicultural education at minzu universities for ethnic minorities in China, offering insights into their unique role within a complex national identity framework.

* * *

In an increasingly globalized world, the concept of multicultural education has become paramount in fostering inclusive societies that celebrate diversity while promoting unity (Ramirez et al. 2009). The “color-blind” approach (Bonilla-Silva 2014), which aims to treat individuals equally regardless of their racial or ethnic backgrounds, presents itself as a universal solution in educational systems worldwide. However, this approach often overlooks the complex realities of racial and ethnic disparities, raising questions about its effectiveness in addressing the deep-rooted issues of inequality and discrimination in multicultural settings (Bonilla-Silva 2014).

My research delves into the implementation and implications of multicultural education at minzu universities in China’s higher education system. These institutions, dedicated to the education of ethnic minority students, provide a unique context to examine the dynamics of multicultural education in a country that officially recognizes 56 ethnic groups (Clothey 2005; Zenz 2013). Employing qualitative research methods, including ethnographic interviews and participant observations, I conducted research at a prominent minzu university in western China. This site was chosen for its diverse student body and its role in the national strategy to promote ethnic unity and cultural diversity.

The choice of my topic stems from a growing interest in understanding how state-led multicultural policies impact interethnic relations and identity formation within educational settings (Leibold 2019). By examining the nuanced experiences of students and faculty within minzu universities, my study aims to contribute to the broader discourse on multicultural education and its capacity to address or perpetuate ethnic inequalities (Leibold & Chen 2014). The findings offer insights into the complex interplay between policy, identity, and educational practice (Yang 2017; Grose 2019; Robin 2014), shedding light on the broader societal implications of diversity education in a context as diverse as China’s. Through this analysis, I seek to enhance understanding of the potential and limitations of multicultural education in fostering truly inclusive and equitable educational environments (Lhagyal 2021).

Dual Role of Minzu Universities in Ethnic Identity Formation

Minzu universities in China hold a distinctive position within the country’s educational landscape, serving a dual purpose in the formation of ethnic identity among minority students (Clothey 2005). These institutions, designed to cater specifically to the educational needs of China’s ethnic minorities, offer a unique blend of cultural preservation and integration into the broader Chinese national identity (Zenz 2013; Yang 2017). At the heart of the minzu university experience is the endeavor to maintain the linguistic and cultural heritage of ethnic minority students while also integrating them into the Han-dominated national narrative (Clothey 2005). These institutions provide programs in both ethnic minority languages and Mandarin, reflecting a commitment to bilingual education (Zenz 2013; Robin 2014). This approach aims to equip students with the tools needed to navigate the broader Chinese society while retaining a connection to their ethnic roots (Yang 2017).

Research conducted at these universities reveals a nuanced impact on student identity. For Tibetan students, for instance, the environment fosters a heightened awareness of their ethnic heritage and encourages the formation of a modern Tibetan identity that coexists with the national identity promoted by Beijing. This dual identity formation process highlights the universities’ role in creating a space where ethnic minority students can explore and redefine their cultural identities within the context of a dominant national culture.

A curator explains the traditional Tibetan thangka painting to a group of student visitors at a minzu university museum in April 2023.

However, the experiences of students at minzu universities are not without challenges. The push and pull between ethnic and national identities can lead to a complex negotiation of identity for students, who must navigate the expectations and norms of both their ethnic community and the broader Chinese society. By offering an education that straddles ethnic heritage and national integration, minzu universities facilitate a form of identity formation that reflects the complexities of modern Chinese society.

State-Led Multiculturalism and Interethnic Relations

China’s approach to multiculturalism, particularly through its education system, offers a distinctive perspective on managing interethnic relations. Within this framework, minzu universities emerge as pivotal institutions where the nation’s aspirations towards unity in diversity are enacted. These institutions embody state-led efforts to foster multicultural education, aiming to enhance mutual understanding and respect among China’s numerous ethnic groups. My research delves into the effects of such policies on interethnic relations, shedding light on the nuanced outcomes of these endeavors.

State-led multiculturalism in China is characterized by the promotion of ethnic diversity alongside the reinforcement of a unified national identity. Minzu universities play a critical role in this strategy, providing a platform for students from diverse ethnic backgrounds to engage with each other and the nation’s dominant Han culture. The presence of programs that celebrate ethnic minority languages and cultures within these universities illustrates the state’s commitment to diversity. However, the overarching goal remains the cultivation of a cohesive national identity among all students.

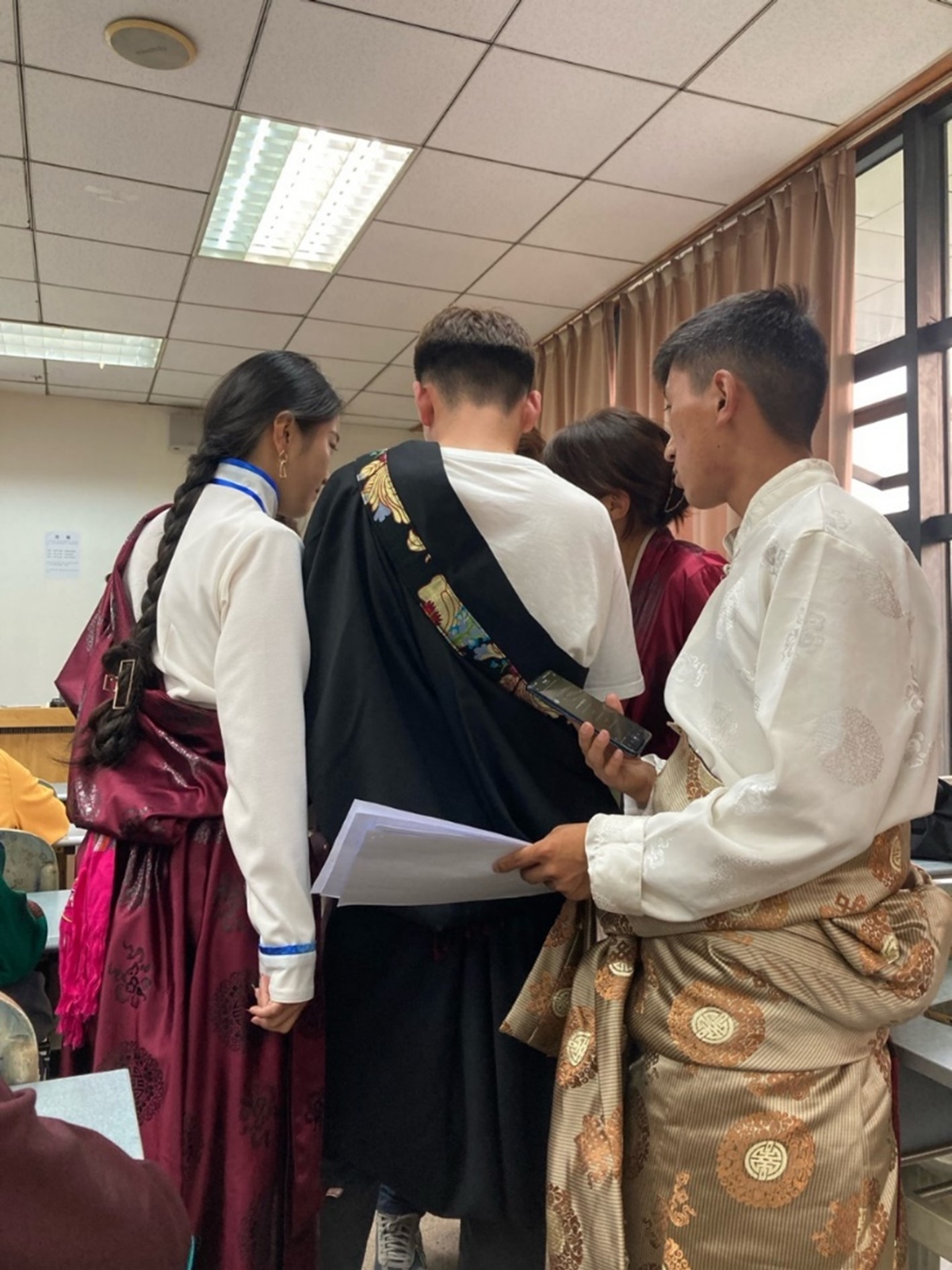

Tibetan students dressed in traditional attire during a university-sponsored campus activity at a minzu university in May 2023.

The impact of this approach on interethnic relations is multifaceted. On one hand, it facilitates encounters and exchanges among students of different ethnic backgrounds, potentially laying the groundwork for increased understanding and solidarity. Students are exposed to a variety of cultural perspectives, which can enrich their personal and intellectual development. On the other hand, the emphasis on a unified national identity might overshadow the distinctiveness of minority cultures, complicating the process of identity formation for minority students.

These dynamics underscore the complexity of implementing state-led multiculturalism in a society as diverse as China’s. While aiming to harmonize interethnic relations, the challenge lies in balancing the celebration of ethnic diversity with the promotion of national unity. Through the lens of minzu universities, we gain insight into both the achievements and challenges of this endeavor, highlighting the ongoing negotiation of identity and belonging in China’s multicultural landscape.

Institutional and Structural Challenges in Ethnic Inequality

In the diverse landscape of China’s higher education, minzu universities represent a critical effort to integrate ethnic minority students into the national fabric while respecting their unique cultural identities. However, these institutions face the monumental task of addressing and overcoming ethnic inequalities within an educational and societal context.

At the core of minzu universities’ mission is the goal of fostering an environment where students from all ethnic backgrounds can thrive academically and socially. These universities are designed to be inclusive spaces that not only educate but also promote understanding and respect for cultural diversity. They offer programs in minority languages and culture, aiming to elevate the status of ethnic minorities within the broader society.

Despite these commendable efforts, challenges persist in fully addressing the deep-rooted inequalities that affect ethnic minority students. One of the primary obstacles is the delicate balance between celebrating diversity and ensuring equal opportunities for all students. While the curriculum and extracurricular activities at minzu universities strive to highlight ethnic traditions and languages, ensuring that diversity does not translate into disadvantage remains a constant challenge.

Moreover, the structural limitations within the educational and societal system can sometimes hinder the full realization of these goals. For example, the transition from education to employment remains a significant hurdle for many ethnic minority graduates, reflecting broader societal patterns of inequality.

Understanding the institutional and structural challenges faced by minzu universities in addressing ethnic inequalities is crucial. These institutions stand at the intersection of cultural preservation and societal integration, embodying the complexities of navigating ethnic diversity within a rapidly modernizing nation. Examining their efforts offers insights into both the progress made and the hurdles that remain, highlighting the nuanced journey toward achieving equality and inclusion for all ethnic groups in China.

Toward a More Inclusive Multicultural Education

China’s innovative approach to multiculturalism within its higher education system, particularly through the minzu universities, represents a significant endeavor to integrate ethnic diversity with national unity. These institutions serve as a focal point for exploring the intricate balance between celebrating ethnic identities and fostering a cohesive Chinese national identity. They not only provide education in minority languages and cultures but also serve as a microcosm for understanding broader societal dynamics. The dual identity formation process they facilitate highlights the potential for creating a more inclusive national identity that acknowledges and respects ethnic diversity.

The state-led approach to multiculturalism has had a nuanced impact on interethnic relations. While it promotes interactions among diverse student bodies, fostering understanding and solidarity, it also faces the challenge of ensuring that the richness of minority cultures is not overshadowed by the overarching narrative of national unity. The experiences of students within these universities underscore the delicate balance between celebrating diversity and achieving cohesion.

Institutional and structural challenges persist in fully addressing ethnic inequalities within the education system. Despite efforts to promote equality and inclusion, disparities in educational outcomes and experiences among ethnic groups indicate areas for further reflection and improvement.

China’s minzu universities embody the country’s commitment to navigating the complexities of multicultural education. Their role in shaping the future of ethnic relations and national identity in China is both critical and evolving. As these institutions continue to navigate the challenges and opportunities presented by the country’s diversity, they serve as a valuable case study for understanding the broader implications of multiculturalism in education. I hope my research will provide a foundation for further analysis and deeper understanding of the dynamics at play in one of the world’s most populous and culturally diverse countries.

References

Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2014. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States, 4th ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Clothey, Rebecca. 2005. “China’s Policies for Minority Nationalities in Higher Education: Negotiating National Values and Ethnic Identities.” Comparative Education Review, 49(3), pp. 389–409.

Grose, Timothy. 2019. Negotiating Inseparability in China: The Xinjiang Class and the Dynamics of Uyghur Identity. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Leibold, James. 2019. “Planting the Seed: Ethnic Policy in Xi Jinping’s New Era of Cultural Nationalism.” China Brief, 19(22), pp. 9–14.

Leibold, James, and Yangbin Chen, eds. 2014. Minority Education in China: Balancing Unity and Diversity in an Era of Critical Pluralism. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Lhagyal, Dak. 2021. “‘Linguistic Authority’ in State-Society Interaction: Cultural Politics of Tibetan Education in China.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 42(3), pp. 353–367.

Ramirez, Francisco O., Patricia Bromley, and Susan Garnett Russell. 2009. “The Valorization of Humanity and Diversity.” Multicultural Education Review, 1(1), pp. 29–54.

Robin, Françoise. 2014. “Streets, Slogans and Screens: New Paradigms for the Defence of the Tibetan.” In Trine Brox and Ildikó Bellér-Hann, eds., On the Fringes of the Harmonious Society: Tibetans and Uyghurs in Socialist China. Copenhagen: Nias Press, pp. 209–235.

Yang, Miaoyan. 2017. Learning to Be Tibetan: The Construction of Ethnic Identity at Minzu University of China. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Zenz, Adrian. 2013. “Tibetanness” Under Threat?: Neo-Integrationism, Minority Education and Career Strategies in Qinghai, PR China. Leiden: Brill.