The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the learning environment in South Africa includes challenges in adjusting to online teaching and the impact of trauma, 2012 Sylff fellow Liza Hamman says. To address stress and anxiety among learners and educators and help create a positive learning environment, Hamman developed an online mindful training course for South African educators using a Sylff Leadership Initiatives grant.

* * *

The countrywide lockdown imposed by the South African government in March 2020 changed the South African education landscape rapidly and radically. Educators and learners, who were accustomed to teaching and learning in a face-to-face classroom environment, had to adjust to online teaching methods suddenly and without warning. The learning curve was steep for both educators and learners, but those learners who at least had access to online resources were the lucky ones. Unfortunately, many learners in South Africa do not have access to the resources needed to engage in online learning.

As an educator, I witnessed the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the learning environment firsthand. In my experience, a handful of students engaged with the online content and continued learning, while most trailed behind because they were unable to afford the devices, or the data, needed for this engagement. On the other hand, educators struggled to cope with this new approach to teaching. In South Africa, even before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, educators faced many challenges including classroom size, an increasing administrative workload, language barriers, and increasing incidents of violence in schools. Already overwhelmed educators now had to face even more challenges that they were not prepared for and received very little support in dealing with.

Furthermore, the learners they teach often face social challenges such as lack of adequate income, housing, and healthcare. South Africa is among the most unequal societies in the world, and many students come from communities where unemployment is endemic, gang and domestic violence is commonplace, and drug and alcohol misuse is widespread. These circumstances are frequently an everyday occurrence in unequal societies and result in “chronic trauma” for those living in these communities (Ebersöhn 2019, S2).

It can be safely assumed that as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, poverty and unemployment have increased in South Africa, as well as the associated trauma. Wartenweiler (2017) states that “acknowledging the impact of trauma on learning is of great importance if we want to create a more socially just education system and not disadvantage traumatised learners.”

The Impact of Trauma on the South African Education System

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, McGowan and Kagee (2013, 336) noted that South Africa is “a society characterized by high rates of violence and trauma.” Similarly, John (2016) found that trauma and fear are often a reality in the South African learning environment, which can impede the learning process. Traumatized learners display such symptoms as depression, guilt, shame, lack of confidence, disturbed sleep, inability to concentrate, chronic stress conditions, and panic attacks, among others. For learners who are traumatized, learning is obstructed by anxiety, fear, and poor concentration (Kerka 2002). As a result of the aforementioned challenges that both educators and learners face, educators are struggling to deliver a level of education that will lay a strong foundation for much-needed economic growth and social change in South Africa.

Due to the consequences of trauma and other challenges faced by educators, stress, anxiety, and burnout are a prominent problem among educators in a South African context. Peltzer et al. (2009) found that stress levels are high among South African educators, with many educators reporting lack of job satisfaction associated with stress-related illnesses such as stomach ulcers, hypertension, mental distress, and alcohol misuse. Peltzer et al. (2009) report that lack of support for educators in South Africa is one of the leading reasons for high stress levels and educators leaving the profession. Furthermore, high stress levels have a negative impact on the quality of education delivered.

In support of the above-mentioned view, Jennings and Greenburg (2009) found that burnout and emotional exhaustion among educators have a negative impact on learner performance. Additionally, the classroom environment created by burned-out educators can have a negative effect on the social and emotional health of students. The student’s learning environment is mainly created by the educator, and it was found that socially and emotionally competent educators create a classroom environment that is more conductive to learning and fosters positive development.

Finding Ways to Address Trauma in the South African Education System

It is clear from the academic literature, as well as my own experience, the experience of my colleagues, and the learners that we teach, that there is a need to address trauma and emotional issues in educational settings. Authors such as Jennings and Greenburg (2009) recommend mindfulness as a way to deal with these challenges.

It is clear from the academic literature, as well as my own experience, the experience of my colleagues, and the learners that we teach, that there is a need to address trauma and emotional issues in educational settings. Authors such as Jennings and Greenburg (2009) recommend mindfulness as a way to deal with these challenges.

On a personal level, I have been interested for many years in mindfulness and methods that cultivate mindfulness. I was introduced to mindfulness and the practices that cultivate mindfulness for the first time in 2009. Since then, my interest in mindfulness, and how it can support education and learning, grew out of my own need to find improved ways to deal with my own stress, as well as my students’. My own experience, of introducing mindfulness in my own life and eventually to my learners, mirrored the views expressed in the academic literature—that mindfulness has the potential to address both educators’ and learners’ stress and anxiety.

Many authors assert that teaching people mindfulness will reduce stress, decrease burnout, promote self-esteem and a sense of well-being, enhance awareness of multiple perspectives, and induce the ability to reframe contexts and engage in the present moment. Furthermore, it will promote equanimity and wakefulness and enhance the ability to focus one’s attention (Kabat-Zinn 1994; Newman 2008; Shapiro, Brown, and Astin 2011). It is thus probable that mindfulness training will improve educators’ and learners’ emotional competence, resulting in a positive and innovative learning environment that promotes creative learning and development.

Introducing Mindfulness to South African Educators

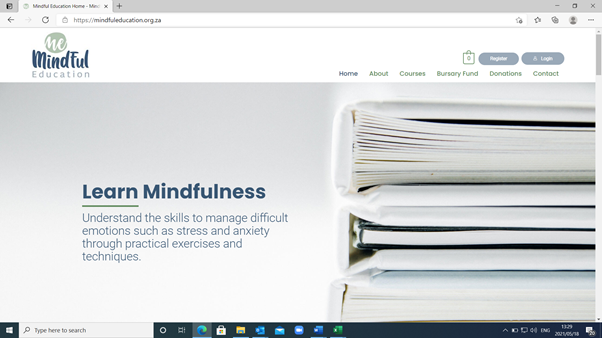

Mindfulness training for educators is a novel concept in South Africa. The number of qualified mindfulness facilitators is limited, and very few are focused on mindfulness training in the education sector. At present, mindfulness training in South Africa is expensive and not readily available and therefore not accessible to all members of society. In pilot studies educators have reported positive results such as decreased stress and anxiety, increased focus, improved ability to handle conflict, and improved communication with students as a result of mindfulness training (Napoli 2004). Yet the lack of availability and cost of mindfulness training in South Africa will prevent educator participation in such courses.

As an educator and a certified mindfulness facilitator, I realized that there was a need to develop a course that is accessible to all South African educators. I believe that one of the most effective routes to provide mindfulness training to more people will be through the education system. Introducing educators to mindfulness and providing them with mindfulness techniques to pass on to their students will ensure that more members of South African society will have access to mindfulness training.

Responding to this need, and with a Sylff Leadership Initiatives (SLI) award from the Sylff Association, I developed an online mindfulness training course adapted to the needs of South African educators. The course is offered online not only to reduce the cost of facilitation, but also to make it accessible to educators across South Africa. In this way, it can reach educators and learners from underprivileged educational institutions as well as educators who live in rural areas. Additionally, although the concept of this course was developed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the crisis further supported the appropriateness of an online solution.

The duration of the course will be eight weeks, during which educators will learn to manage and reduce their own stress and anxiety. They will also be introduced to simple techniques that they can pass on to their learners. The course is in its infant stages at the time of this writing, and the first pilot course is about to be launched. I will only be able to measure the impact of the training once the first participants have completed the course.

Conclusion

It is my hope that this online mindfulness training course for South African educators will provide them with much-needed support. I believe that if we take care of our teachers, we can improve the quality of education in South Africa, because educators will have the mental capacity to create a positive learning environment that is conducive to learning. The quality of education is vital to enabling students to become economically productive and sustain their own livelihood, supports individual well-being, and contributes to peaceful and democratic societies. Education can provide the foundation for economic growth, social change, and transformation that is much needed in South African society.

Lastly, online mindfulness training for South African educators has the potential to make a contribution toward addressing the social dilemma of chronic trauma, stress, and anxiety in South African society.

References

Ebersöhn, Liesel. 2019. “Training Educational Psychology Professionals for Work Engagement in a Context of Inequality and Trauma in South Africa.” Supplement, South African Journal of Education 39, no. S2: S1–S25.

Jennings, Patricia A., and Mark T. Greenburg. 2009. “The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom Outcomes.” Review of Educational Research 79, no. 1: 491–525.

John, Vaughn M. 2016. “Transformative Learning Challenges in a Context of Trauma and Fear: An Educator’s Story.” Australian Journal of Adult Learning 56, no. 2: 268–89.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 1994. Catalyzing Movement Towards a More Contemplative/Sacred-Appreciating/Non-Dualistic Society. Pocantico, NY: The Nathan Cummings Foundation & Fetzer Institute.

Kerka, Sandra. 2002. “Trauma and Adult Learning.” ERIC Digest no. 239: 1–8.

McGowan, Taryn C., and Ashraf Kagee. 2013. “Exposure to Traumatic Events and Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress among South African University Students.” South African Journal of Psychology 43, no. 3: 327–39..

Napoli, Maria. 2004. “Mindfulness Training for Teachers: A Pilot Program.” Complementary Health Practice Review 9, no. 1: 31–42.

Newman, Michael. 2008. “The ‘Self’ in Self-Development: A Rationalist Meditates.” Adult Education Quarterly 58, no. 4: 284–98.

Peltzer, Karl, Olive Shisana, Khangelani Zuma, Brian Van Wyk, and Nompumelelo Zungu-Dirwayi. 2009. “Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Stress-Related Illnesses among South African Educators.” Stress and Health 25, no. 3: 247–57.

Shapiro, Shauna L., Kirk Warren Brown, and John A. Astin. 2011. “Toward the Integration of Meditation into Higher Education: A Review of Research Evidence.” Teachers College Record 113, no. 3: 493–528.

Wartenweiler, Thomas. 2017. “Trauma-Informed Adult Education: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.” The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education 7, no. 2: 96–106.