Using an SRA award, Kyla Zaret, a 2018 Sylff fellow from Portland State University, visited Southwest Patagonia in Chile to conduct fieldwork from March to May 2019. She has been continuously visiting this area since 2003, when she was enchanted by the natural beauty of the region. After learning approaches to conservation and development during her master’s program, she began building networks with local people and stakeholders. Her Sylff SRA fieldwork was based on her long-term commitment and experiences.

***

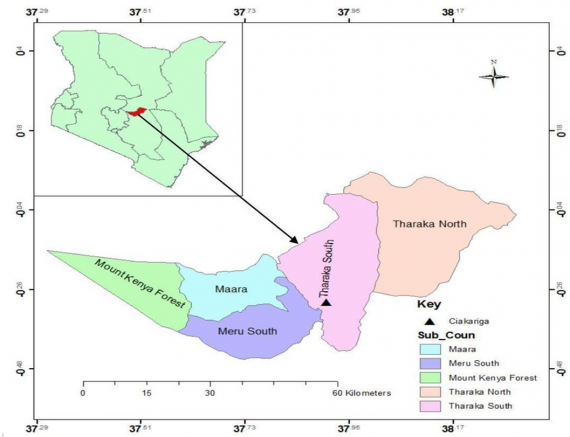

Patagonia looms large in the imaginations of individuals across the world, though many people are surprised to learn that the region encompasses more than one million square kilometers and extends from Chile’s fjords in the west to Argentina’s cliff-lined coast to the east, thus traversing both the Andes Mountains and national borders. While the global mythos of Patagonia as a pristine landscape of rivers flowing freely from glaciated peaks through primeval rainforest or across windblown steppe is not entirely false, it does belie the region’s historic and current patterns of land use and landscape change, which are becoming increasingly influenced by climate change and globalization. My academic research and goals as a Sylff fellow are responses to my first-hand experiences of how the above factors affect Patagonia’s ecosystems and people and my desire to lead conservation efforts that transcend socio-political boundaries to engage a diversity of stakeholders in fostering the resilience of this critical, yet vulnerable, region of the world.

Mosaic of burned wetlands and forests along the Vargas River, which parallels the “Southern Highway” and flows into the Baker River (also shown) in the Aysén Region, Chilean Patagonia. Photo by Adam Spencer, 2017.

I first arrived in Patagonia in 2003 as a backpacker, eager to explore the region’s remote and rugged beauty; however, my perspective of people and place has since deepened, as has my commitment to generating positive social change. I began conducting scientific fieldwork in southwest Patagonia in January 2010 while completing an independent research project as part of the International Conservation and Development option of the master’s program in which I was enrolled at the University of Montana (UM). I chose to undertake my practicum in Patagonia because observations that I had made during my initial travels (e.g., the conversion of native forest to nonnative tree plantations, evidence of landscape-scale fires, and a controversial hydroelectric project that would displace families from their homesteads) inspired numerous questions about natural resource management and environmental justice—questions that catalyzed my pursuit of graduate study.

Through the interdisciplinary program at UM, I learned approaches to conservation and development that prioritize local peoples’ knowledges, needs, and perceptions while striving to promote the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem function. Within the doctoral program at Portland State University (PSU), I have been applying those teachings and building upon my master’s research to investigate how patterns of social interaction influence whose information and knowledge about altered ecosystems becomes integrated into decision-making processes, thus determining the next trajectories of ecological and social change. This research is needed because land use practices such as burning, logging, and, more recently, peat moss harvest, continue to dramatically alter the mosaic of temperate rainforests and wetlands (i.e., the “forest-peatland ecotone”) that characterize the landscape of southwest Patagonia, calling into question the continued resilience of sensitive ecosystems and the human communities who depend upon them.

A burned forest site that was once dominated by the cedar tree Pilgerodendron uviferum (Ciprés de las Guaitecas) but is now being harvested for the peat moss Sphagnum magellanicum (pon pon or pompoñ).

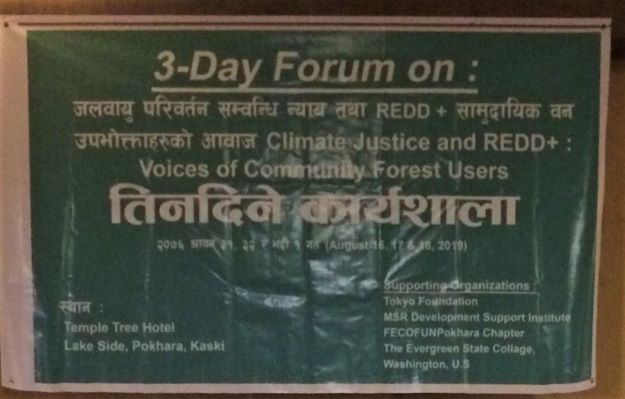

Historically, poorly drained sites along river valley bottoms in southwest Patagonia were dominated by a slow-growing, rot-resistant cedar tree (Pilgerodendron uviferum), whose harvest and sale formed the cornerstone of local people’s livelihoods and cultural identities, as I learned through my master’s research (Zaret 2011). Currently, however, almost all of these sites are characterized by fire-charred snags and stumps that rise from a saturated carpet of red-orange peat moss (Sphagnum magellanicum), and the cedar tree is listed as a globally threatened species (IUCN 2010). The change in dominance from cedar tree to peat moss is reflected in a transition in the resource use of these sites: in some parts of southwest Patagonia, people have shifted from harvesting cedar to harvesting peat moss. Thus, trade-offs must be made in the socio-political-economic realm regarding which potential ecosystem services of these now nonforested sites should be encouraged through management decisions. For example, should the keystone species and culturally iconic cedar tree be restored to burned sites, or is there greater perceived value in maintaining such sites in their current state of enhanced peat moss growth (e.g., so as to allow for continued harvest and sale of the moss to the horticulture market)? Conflicts are starting to arise between managers and landowners and other resource users given the passage of a new national law (Decreto 25, August 2019) that regulates the harvest of peat moss on public and private lands. Deciding how best to manage these cedar–peat moss (or “forest-peatland”) sites is further complicated by a dearth of information: none of Chile’s state agencies have been dedicated to wetland management, and very little knowledge is held by agency personnel regarding these altered ecosystems (Fernán Silva, Agricultural Service, pers. comm.).

In response to this situation, my dissertation has two overarching goals, which pertain more to the ecological or social domain of forest-peatland resource use and management of southwest Patagonia. My first goal incorporates ideas of ecosystem resilience (e.g., Holling 1973) and ecological tipping points (e.g., Scheffer and Carpenter 2003) to investigate patterns and mechanisms of ecosystem change across waterlogged sites in southwest Patagonia due to altered climate and fire regimes. I am working on this goal using forest reconstructions, paleoecological data, and vegetation surveys at control and burned sites to compare historical and contemporary relationships between climate, fire, and vegetation. My second goal is to evaluate whether the network of stakeholders engaged in natural resource use and management is structured so as to foster “social learning” (e.g., Muro and Jeffrey 2008), which may be a prerequisite for managing the complex (and novel) multiscalar dynamics of ecosystems comprising this ecotone (Folke et al. 2005). This goal has been made possible by the Sylff Graduate Fellowship and Sylff Research Abroad (SRA) award, which have allowed me to complete the qualitative and quantitative data collection needed to apply the technique of social network analysis (e.g., Bodin and Crona 2009).

Old-growth cedar trees (Pilgerodendron uviferum) rise in the distance beyond tall bulrushes in an unburned area of the Exploradores Valley of the Aysén Region, Chilean Patagonia.

The social dimension of my dissertation research is driven by my interest in whether actors who differ in their capacities (or power) to make decisions that strongly affect their occupations or livelihoods (e.g., governmental land managers vs. resource-dependent landowners or resource harvesters) communicate their knowledge and observations of the natural world with one another. This exchange is needed not only in order to best understand rapidly changing ecological dynamics but also to assure that the perspectives and needs of all stakeholders are taken into account in the management process. Thus, my SRA project was designed to help me answer the research question: Can patterns of information and knowledge exchange within the egocentric networks of distinct socio-political actors be explained by (a) the distribution of relational ties that are constrained, voluntary, or imposed by a third party (i.e., “terms of connection”; Rocheleau and Roth 2007: 434), and/or (b) scale-related differences in perspectives regarding the value(s) of forest-peatland sites?

To begin answering the above question, I conducted fieldwork in the Aysén Region of southern Chile from March to May 2019. (Aysén is where I completed my master’s research and where I have been building my own social network since 2010.) There, I traveled from the capital city of Coyhaique to rural towns and homesteads, engaging in participant observation, meeting with key informants, identifying stakeholders and potential research participants, and conducting semistructured interviews. To find and recruit interview participants, I used purposive snowball sampling to locate individuals representing opposite ends of the socio-political scale ranging from high-interest, low-power individuals to high-interest, high-power individuals. Ultimately, I conducted participant observation with 26 individuals from the land management, commercial, natural resource harvest, and nonprofit science, education, and conservation sectors, and I conducted 12 semistructured interviews (8 with individuals on the high-interest, high-power side of the socio-political scale and 4 with individuals of high interest but low power). This small sample size, especially of low-power individuals, reflects (1) the limited numbers of individuals who are currently regularly engaged in forest-peatland resource use in Aysén[1] and (2) the degree of distrust characterizing landowners’ and resource users’ relations with land managers. That is, a recent campaign by land managers to inform stakeholders of the new rules to be instituted under Decreto 25 resulted in feelings of frustration, and even persecution, on the part of landowners and resource users. Thus, when I arrived at people’s homesteads to discuss the subject of peat moss harvest, many individuals and families were still aggravated over their interactions with land managers. While some people were still open to talking with me—perhaps given my perceived neutral role as a foreign researcher—I felt it inappropriate to request a formal, recorded interview unless I had some prior history and establishment of trust with the research participant.

A view from within a stand of old-growth cedar (Pilgerodendron uviferum) in the Exploradores Valley of the Aysén Region, Chilean Patagonia.

My SRA fieldwork was most productive in terms of connecting me with land managers from the Agricultural Service who will be responsible for implementing the new regulations under Decreto 25. They are actively engaged in building their capacity to understand and monitor the dynamics of forest-peatland sites and to conduct effective education and outreach campaigns. Given my prior work with Round River Conservation Studies (RRCS), a conservation organization that leads study abroad programs for undergraduates and that has been partnering with land management agencies in Aysén since 2012, I was able to participate in several meetings with the Agricultural Service in which I advocated for the recognition of landowners’ and resource harvesters’ knowledge and perspectives. During one of those meetings, a commitment was formed between RRCS and land managers to jointly host a series of workshops for landowners and resource harvesters in which a primary objective would be creating an opportunity to share their experiences and knowledge of forest-peatland sites and to offer feedback on land managers’ activities and regulatory tools.

Back in the United States, I am currently in the process of coding interview data in preparation for conducting the social network analysis (SNA). Following the methods of Knoke and Yang (2008) and Prell (2012), I will map, analyze, and compare the egocentric networks of my research participants in terms of the proportion and quality of information- and knowledge-exchange ties that occur between individuals of the same versus different socio-political scales. These egocentric network maps will display social actors as nodes of different shapes (depending on their socio-political scale) that are connected by arrows, whose direction will indicate whether the exchanges are unidirectional or mutual and whose thickness will represent the quality of the exchange (e.g., whether voluntary or imposed; Rocheleau and Roth 2007). I will use content analysis of the interviews to qualitatively interpret patterns of information and knowledge exchange in the maps in light of people’s own perceptions of their socio-political scales and the value/importance they attribute to forest-peatland sites and their own observations of the natural world.

My preliminary findings, from participant observation and informal conversations, suggest that despite land managers’ new imperatives to identify and communicate with stakeholders, the flow of knowledge and information within and across socio-political scales is currently impaired due to the following: (1) landowners’ frustrations with past interactions with land managers; (2) landowners’ and resource harvesters’ lack of awareness of or appreciation for their own knowledge of the natural history of forest-peatland sites; (3) land managers’ lack of recognition of landowners and resource users as legitimate knowledge holders; and (4) structural aspects of regional institutions that limit communication between land managers, even within a single agency. Ultimately, I hope that the network maps—the visual products emerging from this research—can be used to pinpoint and convey where efforts to enhance communication and collaboration between stakeholders have the best chance to ensure that all perspectives and insights are brought into play to guide the wise use and continuing availability of natural resources in southwest Patagonia. I also intend to use the outcomes of my research to draw attention to other understudied nonboreal forest-peatland ecotones of the world. These areas have received scant attention from the global scientific community despite their vulnerability to climate change and their potential to contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions if burned (Davies et al. 2013), thus threatening the resilience of local and nonlocal ecosystems and actors.

The Sylff fellow, so excited to have finally located an old-growth stand of cedar trees (Pilgerodendron uviferum) in the Exploradores Valley of the Aysén Region, Chilean Patagonia.

As a Sylff fellow and SRA awardee, I am thankful to have been able to expand my dissertation to include a social line of inquiry that (1) will generate new conceptual and methodological links between governance, scale, and social network theory that pertain to knowledge and information exchange regarding the use and management of altered ecosystems and (2) has an applied goal of active “network weaving” (Vance-Borland and Holley 2011). In this way, I feel that I am becoming a conservation scientist and practitioner who works to transform environmental governance into a process that is equitable and inclusive for all natural resource stakeholders.

References

Bodin, Ö., and B.I. Crona. 2009. The role of social networks in natural resource governance: What relational patterns make a difference? Global Environmental Change 19 (3): 366–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.05.002.

Davies, G.M., A. Gray, G. Rein, and C.J. Legg. 2013. Peat consumption and carbon loss due to smouldering wildfire in a temperate peatland. Forest Ecology and Management 308 (November): 169–77.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2013.07.051.

Folke, C., T. Hahn, P. Olsson, and J. Norberg. 2005. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environmental Resources, 30: 441–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

Holling, C.S. 1973. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4: 1–23.

Knoke, D., and S. Yang. 2008. Social Network Analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc. http://methods.sagepub.com/book/social-network-analysis.

Muro, M., and P. Jeffrey. 2008. A critical review of the theory and application of social learning in participatory natural resource management processes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 51 (3): 325–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560801977190.

Prell, C. 2012. Social Network Analysis: History, Theory and Methodology. Los Angeles: SAGE Publishing.

Rocheleau, D., and R. Roth. 2007. Rooted networks, relational webs and powers of connection: Rethinking human and political ecologies. Geoforum 38 (3): 433–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.10.003.

Scheffer, M. and S.R. Carpenter. 2003. Catastrophic regime shifts in ecosystems: Linking theory to observation. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 18 (12): 648–656.

Vance-Borland, K. and J. Holley. 2011. Conservation stakeholder network mapping, analysis, and weaving: Conservation stakeholder networks. Conservation Letters 4 (4): 278–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00176.x.

Zaret., K. 2011. Distribution, use and cultural meanings of ciprés de las Guaitecas in the vicinity of Caleta Tortel, Chile. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Montana.