Sylff fellow Louis Benjamin has been proactively engaged in early childhood development in his home country of South Africa through the Basic Concepts Program. Developed by Benjamin, who has incorporated the contexts of the South African educational system into education for preschool and early primary school students in disadvantaged communities, the Basic Concept Program undertakes “a structured metacognitive intervention approach for educators to address language, learning, information processing and socio-emotional barriers in young children, particularly from disadvantaged communities” (quoted from the Basic Concepts Unlimited website: http://www.basicconcepts.co.za/about/about). Benjamin believes in the immense potential of early educational intervention for children in disadvantaged communities, which generates lasting impact on their motivation for learning, thereby contributing to their higher educational achievement for better career opportunities. Benjamin has received a Sylff Project Grant (SPG) to disseminate the Basic Concepts Program in the Northern Cape, one of the poorest provinces in South Africa. Over the three years of the SPG period and beyond, Benjamin is trying to achieve his vision to provide the program to all preschool and early primary school children through workshops and follow-ups for school teachers of the province.

* * *

I am most honored to have been awarded a Sylff Project Grant for the next three years. The funding will be used to implement an early years intervention program for children run by class teachers in the Northern Cape, South Africa. The program is called the Basic Concepts Program (BCP) and aims to improve both teaching and learning in the preschool years and first three years of formal schooling. The BCP was developed by me during my PhD degree at the University of the Western Cape, which was generously funded by Sylff.

I am a native of the Northern Cape. I grew up and was educated in the diamond town of Kimberley, a town well known for its Big Hole dating back to the Diamond Rush at the turn of the twentieth century. It is therefore no surprise that I was drawn back to the province that holds my earliest and most precious memories. The Northern Cape is the largest province in the country but is also the most sparsely populated. Although it is endowed with many mineral deposits, the Northern Cape is one of the poorest and least developed provinces. More than half the population in the province lives in abject poverty (Statistics South Africa [Stats SA], Poverty Trends in South Africa, 2017). Research has shown that children from poor socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to fare poorly at school and/or drop out and have poor educational and vocational opportunities (as cited in the OECD Report Equity and Quality in Education, 2012), and the Northern Cape is no exception. Although approximately 87% of children attend school, only 1.5% attain a tertiary qualification (Stats SA, 2016). The Northern Cape has the second highest (28%) illiteracy rate in South Africa (Stats SA, 2016).

There is a critical need to improve these educational outcomes if children in the province are to break out of the poverty cycle. The focus of the current project is to give children who are starting school a preparatory boost to ensure that they are able to learn successfully when they receive formal instruction and are taught how to read, write, and calculate. The research data we have gathered over the years (2008–2018) show that the majority of learners who start school are very poorly prepared for school learning. These children without exception come from moderately to severely deprived living circumstances and consequently have limited exposure to the kind of early childhood experiences that would have prepared them for formal, higher-order school learning.

What Is the Basic Concepts Program?

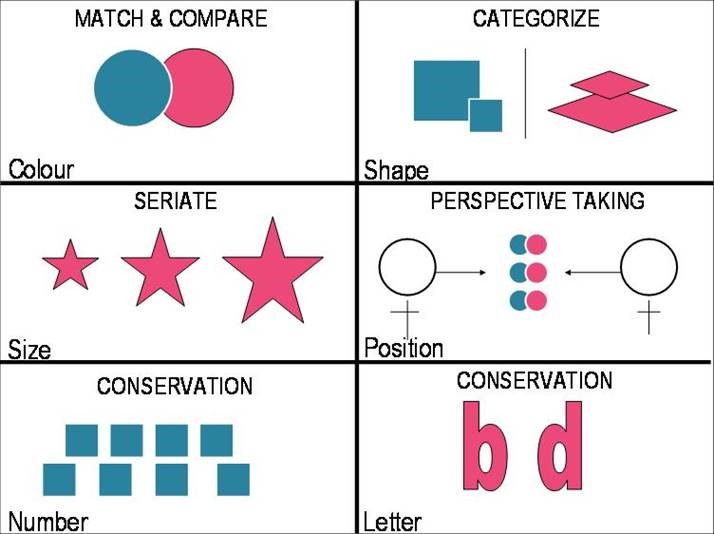

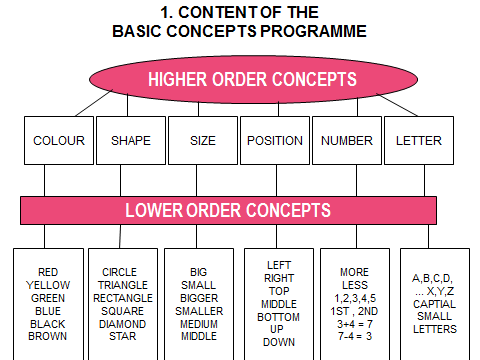

In the BCP, there is a focus on both the development of cognitive processes, such as accurate perception, matching, comparing, classifying, seriation, perspective taking, and conservation (Figure 1), and the expansion of understanding of conceptually structured content (Figure 2). The content of the BCP includes the following higher-order conceptual domains: color, shape, size, position, number, and letter and their associated subordinate concepts. These concepts are used to mediate the cognitive processes in the program and are particularly important for children who have not had adequate early childhood educational experiences or who start school with deficient language abilities. The BCP thus provides the classroom teacher with an extensive higher-order conceptual language for instruction that is easily transferrable and linked to the curriculum.

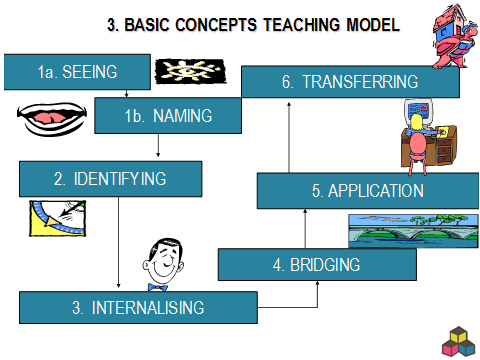

In addition, the Concept Teaching Model (Figure 3) provides a detailed, systematic scaffold for mediators of the program. While the program was developed as a cognitive intervention program, it can also be run in the mainstream classroom to improve teaching and learning. Teachers are trained and assisted to run the program with small groups of learners who need intervention, but in Grade R (Reception Year) the program is used as a curriculum and is run with all learners. While the teacher works with one group on the mat inside, the other learners work on related activities in rotation. The teacher works with each group for approximately 15 minutes and sets aside around 60 minutes per day to run the BCP sessions.

The Northern Cape Province was one of the first provinces to introduce the BCP. I in fact started my work in the province while I was still busy with my PhD. I conducted a trial of the program in the Namaqua Education District in collaboration with the Rural Namaqualand Education Trust (RNET), starting our work in a small cluster of schools before expanding to around 80 Grade R classes.

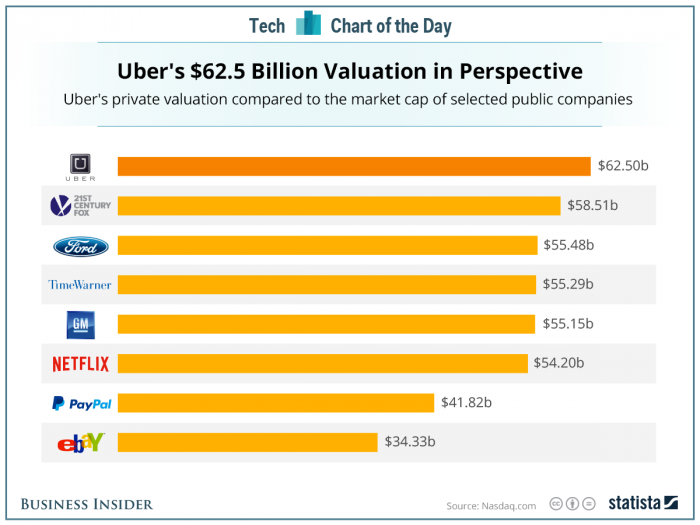

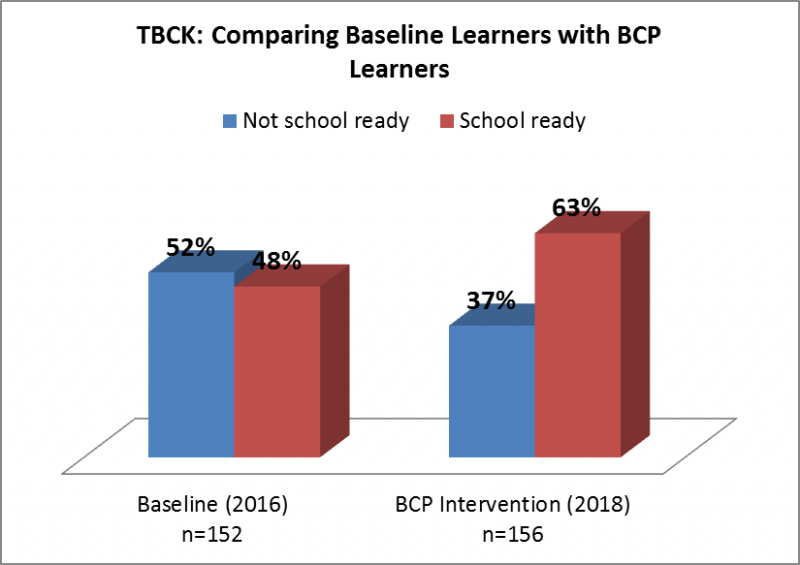

The results of the initial pilot projects were recognized by the Northern Cape Department of Education, which wanted to extend the program and make it available to all its Grade R teachers. (See an example of results in the chart below.) There are approximately 800 Grade R teachers in the province. A Memorandum of Understanding was subsequently signed between Basic Concepts Unlimited (the organization responsible for the Basic Concepts Program) and the Northern Cape government, and the Basic Concepts (BC) Advocacy Project was born. The BC Advocacy Project in the Northern Cape (2019–2023) aims to improve the school preparedness of Grade R learners by between 20% and 30%, thereby improving the overall literacy and numeracy outcomes of learners in the Foundation Phase (Grades 1–3). Baseline testing was done on a sample of Grade 1 learners drawn from the project schools. It showed that a majority (72%) of the learners were not prepared for school learning.

A total of 350 teachers from the districts of the province were selected to participate in the BC Advocacy Project. The district officials are responsible for supporting and monitoring the project teachers, and they will also be responsible for the continuation of the project and the training of the remaining teachers in the province once this project comes to an end.

Phase 1 of the project was initiated at the start of 2019 with approximately 85 teachers in two of the education districts. The teachers have thus far attended four days (out of the six days) of training and have implemented three of the six conceptual domains. Approximately 2,200 learners are receiving intervention. The project is supported and monitored by the local district officials who are ably assisted by teams of mainly retired teacher-volunteers who do regular classroom mentoring visits.

The teachers have already made wonderful progress as they learn to become mediators of the program. We have begun to hear increasingly more complex learner verbalizations while the teachers have become more confident in demonstrating the Concept Teaching Model. The change in the teaching style of teachers has in many cases been dramatic. For many teachers this has been the first time that they have used more interactive and questioning-based approaches in their teaching. The majority had previously used more recitation-based approaches, where the children merely copied what the teacher said. While it is very exciting to see these initial signs of change in these classes, we are aware that it takes time for these to become a permanent part of the teaching repertoire. Admittedly, there have also been some teachers who have required additional support and encouragement to implement the program and to run it on a regular basis. It is for this reason that each phase of the project is run over a period of two years. This allows the teacher time to become a mediator and to use the program with increasing frequency and confidence.

In conclusion, we have been very pleased with what we have observed over the first six months of the project. The teachers have responded positively, and we have also been most encouraged by the response of the local and provincial officials to the project. The enthusiasm for the project remains high, with high levels of participation. As our baseline data show, it is essential that we try to shift the preparedness of the learners in Grade R for school learning. The BC Advocacy Project offers teachers a tool to significantly improve the prospects of their learners. The BCP not only provides teachers with a way to better access their learners but also develops those nascent and often fragile cognitive functions needed for school learning. The core philosophy of the BCP emerges clearly in this project—that children, notwithstanding their circumstances, have the unlimited potential to learn and to continue learning, provided they are given regular classroom mediation by an involved and caring adult.

For more information about the project, please click here.