Two years after Sylff fellows from various countries gathered at the Sylff Leadership Initiatives (SLI) forum held in December 2016, another Sylff gathering was organized in late November 2018 by the great initiative of four SLI organizers—Jacinta Mwende Maweu, Socrates Kraido Majune, Stephen Muthusi Katembu, and Alexina Nyaboke Marucha—and Awuor Ponge, who joined the organizing team. The event invited fifteen fellows from Nairobi, one fellow from Maseno, Kenya, and two fellows from the United States with the support of the Local Association Networking Support (LANS) program. The following is a report written by Socrates Majune on behalf of the organizers. It outlines discussions about the future of the University of Nairobi Chapter and sentiments of several fellows on how Sylff has impacted their lives over time.

* * *

Introduction

This article is about the proceedings of the LANS meeting held by the Sylff University of Nairobi Chapter on November 23, 2018. The basis of this meeting was the Peace Forum held in 2016, whose main recommendation was to ensure that the chapter remains active. Taking advantage of the newly formed LANS support program by the Sylff Association, five fellows—Dr. Jacinta Mwende, Socrates Majune, Alexina Marucha, Steve Muthusi, and Awuor Ponge—successfully organized a networking meeting at the University of Nairobi Towers. The theme of the meeting was “Sylff Fellows as Agents of Change.” In particular, the meeting sought to enhance cohesion among fellows, showcase the experiences of fellows in their pursuit of changing the world, and to discuss the way forward for the chapter.

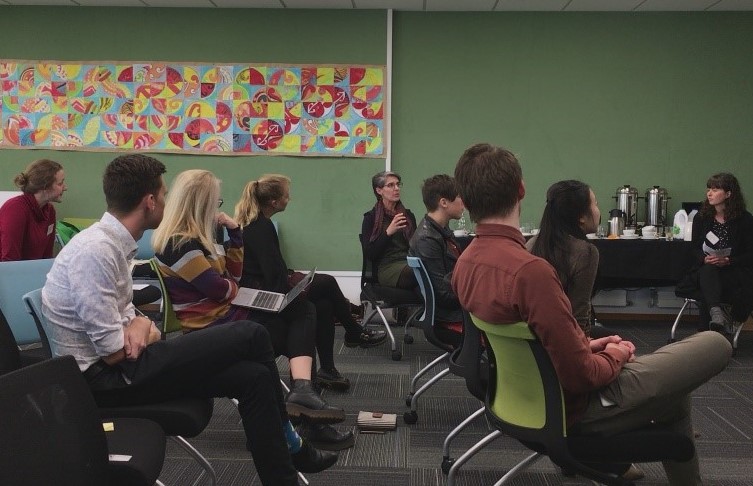

Three organizers: (from left to right) Alexina Nyaboke Marucha, Awuor Ponge, and Socrates Kraido Majune.

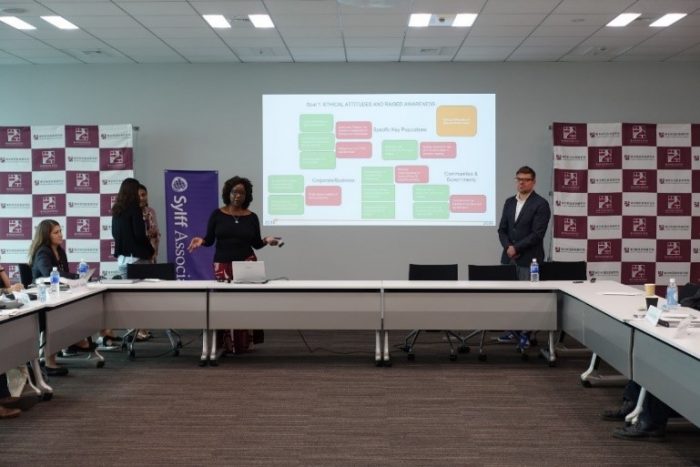

Twenty-two participants attended the meeting: eighteen current and past fellows, two representatives of the Graduate School of the University of Nairobi (Professor Lawrence Ikamari and Mr. Bernard Kiige), one representative of the Sylff Association Secretariat (Ms. Yue Zhang), and a visitor (Mr. Isaac Kariuki). Conspicuous in the meeting was the diversity in terms of period of fellowship, current country of residence, and expertise. The fellowship period spread from 1992–1994 to 2017–2019, and two fellows were from the diaspora (living in the United States), while the rest resided in Kenya. The areas of expertise ranged from academia to policy and think tanks to social action and advocacy.

The meeting began at 12:20 pm and ended at 4:17 pm. The following sections provide summaries of the presentations and deliberations of the meeting.

Presentations

After the official opening of the meeting by Professor Lawrence Ikamari, deputy director of the Graduate School, and a presentation by Ms. Yue Zhang, four fellows presented their experiences as agents of change. Mr. Awuor Ponge, an associate research fellow at the African Policy Centre and adjunct faculty at Kenyatta University, explained how Sylff’s training and networking opportunities have influenced him. Mr. Ponge received the Fellowship between 2007 and 2009 to pursue an MA in Development Studies at the University of Nairobi.

He has so far benefited from three Sylff programs including LANS. The others are: a Sylff Research Abroad (SRA) Fellowship at the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex; the Sylff Administrators Meeting at the Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University in Beppu, which also included a meeting with research fellows of the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research and senior Japanese policymakers in Tokyo. These experiences have particularly brought Mr. Ponge to appreciate multiculturalism, honesty, humility, hospitality, discipline, philanthropy, and academic generosity, virtues that he aspires to in his academic work at Kenyatta University. Moreover, these experiences have enriched his networks and research skills, prompting him to launch the African Policy Centre.

Mrs. Sennane Riungu, a fellow from 2006 to 2008, explained the role of Sylff in her post-undergraduate life. After graduating with a BA in Education, she was unsure of how to proceed until a life-changing opportunity arose in the form of a Sylff fellowship. Through the fellowship, she earned an MA in International Development and Diplomacy, which is the basis of her current work at the Australian High Commission in Nairobi. In 2013, Mrs. Riungu successfully organized a leaders’ forum titled “Leading the Leaders: A Forum for Local Youth Leaders in Maara Constituency.” This was sponsored by the Sylff Association under the SLI support program. Through this initiative, Mrs. Riungu has managed to create a big forum in her constituency that pursues life-enhancing projects such as agri-business opportunities through greenhouse farming.

Dr. Nicholas Githuku, another Sylff fellow, echoed the words of Mrs. Riungu in explaining the impact of the Sylff fellowship in his postgraduate life. He received a Sylff fellowship between 2002 and 2004 to pursue an MA in Armed Conflict and Peace Studies (History) at the University of Nairobi. Though this opportunity, he was able to network and organize a meeting of the Kenya Association of Sylff Fellows in 2005. Dr. Githuku is currently an assistant professor at York College in the United States. His main influence is in academia, especially through his 2015 book titled Mau Mau Crucible of War: Statehood, National Identity, and Politics of Postcolonial Kenya.

Mrs. Agnes Kariuki, one of the earliest Sylff fellows at the University of Nairobi, also made a presentation. She was accompanied by her husband, Mr. Kariuki. She received the fellowship between 1992 and 1994 to study African history at the Department of History, University of Nairobi. She acknowledges the contribution of Sylff in establishing her life purpose of advocating for social action in society. In 1994, Mrs. Kariuki was among the five students selected to take up an internship opportunity in Japan under the support of the Tokyo Foundation and the Mainichi Shimbun. Though her experience with Japanese families, she not only wrote newspaper articles but was also motivated to undertake an AIDS education project together with friends. This was funded by the Tokyo Foundation. Although she relocated to the United States in 1997, her passion for social advocacy remained on course. She established an after-school homework club in a church basement to keep kids off the street and away from crime and help them focus on their studies. This project was originally funded as a social action grant by the Tokyo Foundation but later also attracted funding from such organizations as the YMCA of Metropolitan Washington and IMPACT Silver Spring. As a result of her initiative, Mrs. Kariuki received the prestigious Linowes Leadership Award in 2001 and continues with her initiative with consistent funding from the YMCA. Above all, she teaches at Montgomery County Public Schools and, together with her husband, runs Diasporamessenger, a website that connects Kenyans living in the United States and those intending to visit the country.

Roundtable Meeting and Way Forward

After the aforementioned presentations by fellows, the next section was dedicated to a plenary session among the fellows. The main objective was to propose recommendations to guide the chapter in 2019 and beyond. The major resolutions of the plenary session were as follows:

a) To deepen and strengthen ties among fellows, another LANS meeting will be held in Nairobi in Novembers 2019.

b) The 2019 LANS meeting will be in two parts, a section for academic presentations and a social action program. These would ensure that fellows not only influence one another academically but also impact society. An appropriate theme for the 2019 meeting will be communicated early in 2019. In addition, a mini-meeting will be held earlier in 2019.

c) A database of all fellows will be compiled to ensure that all fellows are involved in the activities of the chapter. This will be accompanied by formal registration of the chapter under the Graduate School of the University of Nairobi.

Conclusion

Looking ahead to the 2019 meeting, it is evident that there is a need to fulfill Sylff’s true mission of tapping leadership skills that make the world a better place. The transmission mechanism was well captured by Mrs. Agnes Kariuki:

The truth is that none of us got to where we are without a helping hand. It is the same helping hand that Sylff has encouraged us to extend to others by becoming agents of change in our communities. It is possible to impact this change through our daily activities so long as we remain focused on making a difference.

Acknowledgments

The organizers of the LANS 2018 meeting would like to immensely thank the Sylff Association for their financial support with the transportation of long-distance fellows. Gratitude also goes to the Graduate School of the University of Nairobi for providing a venue at the University. Lastly, the organizers appreciate the sacrifice of the fellows who attended the four-hour meeting.

List of Participants

|

No. |

Name |

Current affiliation |

Fellowship year |

|

1 |

Robert Josochi |

Anatolia Education Consulting Ltd. |

2015–2017 |

|

2 |

Australian High Commission, Nairobi |

2006–2008 |

|

|

3 |

Desterio Murabula |

Student, University of Nairobi |

2016–2018 |

|

4 |

Henry Kibira |

Lecturer, Maseno University and Laikipia University |

2012–2014 |

|

5 |

Wayne Ngara |

Digital and Outdoor Marketing |

2016–2018 |

|

6 |

Brenda Oloo |

Student, University of Nairobi |

2017–2019 |

|

7 |

Jacob Nato |

Lecturer, Kenyatta University |

2009–2011 |

|

8 |

Miriam Viluti |

University of Nairobi Graduate School |

2016–2018 |

|

9 |

Jane Maina |

Student, University of Nairobi |

2017–2019 |

|

10 |

Maxwell Muthini |

Student, University of Nairobi |

2017–2019 |

|

11 |

Grace Kathure Mugo |

Researcher |

2014–2016 |

|

12 |

Dr. Nicholas Githuku |

York College, United States |

2002–2004 |

|

13 |

Agnes Kariuki |

Montgomery County public schools |

1992–1994 |

|

14 |

Dr. Maweu M. Jacinta |

Lecturer, University of Nairobi |

2004–2006 |

|

15 |

Katembu Stephen Muthusi |

Senior Technologist, University of Nairobi |

2014–2016 |

|

16 |

Embassy of Jordan |

2014–2016 |

|

|

17 |

President, African Policy Centre |

2007–2009 |

|

|

18 |

PhD Student- University of Nairobi |

2013–2015 |

|

|

Non-fellows |

|||

|

19 |

Prof. Lawrence Ikamari |

Deputy Director, Graduate School, University of Nairobi |

|

|

20 |

Mr. Bernard Kiige |

Senior Assistant Registrar, Graduate School, University of Nairobi |

|

|

21 |

Mr. Isaac Kariuki |

Evangelist and founder of Diasporamessenger |

|

|

22 |

Ms. Yue Zhang |

Program Officer, Sylff Association secretariat |

|