In the seventh century, followers of the prophet Mohammed migrated from Arabia to Abyssinia—in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea—where they sought asylum in an ancient Christian state. Known as the First Hijra, this episode represents a legacy of interreligious and interethnic respect, notes 2018–20 Sylff fellow Sara Swetzoff. Ethiopia, whose parliament passed one of the world’s most integrative refugee laws in January 2019, could be an anchor of justice for all of Africa and the Middle East, Swetzoff surmises.

* * *

“If you have to migrate, migrate towards Habash.” —Prophet Mohammed, pbuh (from Ibn Ishaq, Sirat Rasulillah)

Understanding the Recent Conflict in Ethiopia

In November 2020, conflict between national forces and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) touched off a war in Ethiopia. By late 2021, the ongoing violence had reached headlines around the world. The United States pulled all nonessential staff from the embassy in Addis Ababa and revoked trade privileges, sparking protests in Ethiopia and the diaspora. Meanwhile, Tigrayan civilians and human rights advocates documented urgent famine conditions in the region and implored the international community to do more. According to a joint investigation conducted by the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission and the United Nations, both the Ethiopian Defense Forces and TPLF committed ethnically targeted mass atrocities.

To the great relief of the global community, the Ethiopian government lifted the state of emergency in early 2022 and shortly thereafter reached a humanitarian truce agreement with Tigrayan political authorities. The conflict continues, but an ever-expanding proxy war and regional crisis have thankfully been averted.

And yet, the root causes of the conflict still must be addressed. Although there are allegations of outside intervention, many experts agree that the war in Tigray originated internally from a power struggle between national political elites following the major changes to government in 2018. As each camp rallied its social base and escalated military operations, the resulting human rights atrocities transformed the political confrontation into an all-out interethnic conflict, fanning the flames of numerous historical grievances. Until these historical grievances are addressed and robust peacebuilding work takes place, civilians of all ethnic groups will continue to pay the biggest price in every ongoing political conflict.

Seeking the Future in Our Knowledge of the Past

Yet despite the suffering brought upon so many Ethiopians—especially women and children—hope is not lost. From the exciting day in 2018 when Abiy Ahmed first came to power, Ethiopian intellectuals and civil society organizers from all regions and religions have been pushing for a national reconciliation process. In many ways, they predicted this war that has so thoroughly exposed the fragility of the Ethiopian state. In the same vein, they know how to fix it: the recipe for peace is not new, but rather consists of age-old cultural matrices of tolerance, unity, and justice that have sustained Ethiopia throughout the eras.

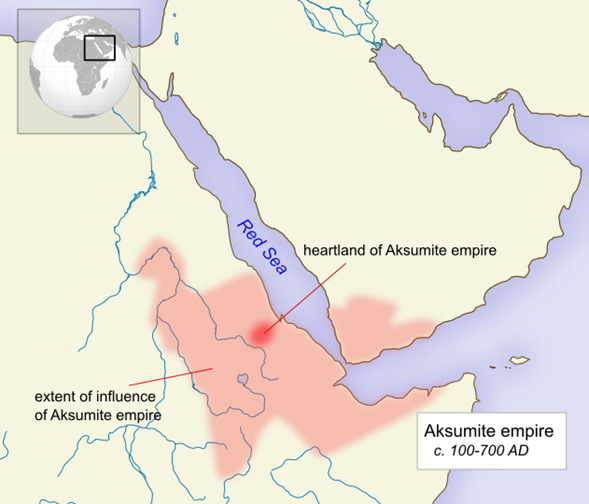

Pan-Africanists might mention as examples the famous anticolonial victory against Italy at Adwa in 1896 or Haile Selassie’s role in preserving the fragile Organization of African States in 1964. But Muslims around the world are likely familiar with a much earlier example of Ethiopian peacebuilding: the Migration to Abyssinia, or the First Hijra.

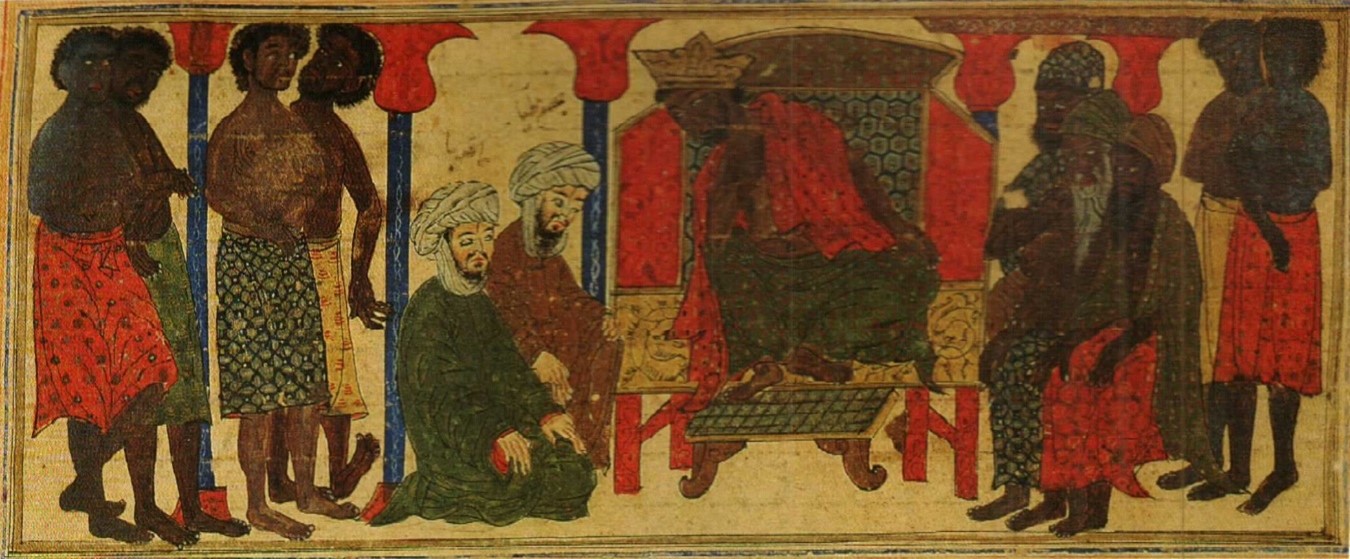

In the year 7 Hijri (613 CE), a group of the Prophet’s first followers (al-Sahabah) including Umar Ibn Afnan sought asylum in the Christian kingdom of Axum at the invitation of the Negus, or King, referred to as “Al-Najashi” in Arabic sources. Two years later, they were joined by a second, larger group; according to Tafsir Ibn Kathir, the 117 Muslims residing in Ethiopia outnumbered those who stayed in Mecca by almost threefold at the time of their arrival. Within a decade, most of the group returned to Arabia and headed to Madinah. Others settled in what is now Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia, and still others set sail for various destinations across southeast Asia.

One might argue that the survival—and subsequent growth—of the early Muslim community was due to the Axumite Kingdom’s generosity and tolerance. In Muslim traditions, Al-Najashi was not just a passive host; he wept at the recitation of the Holy Quran, provided feasts for special events (such as the long-distance marriage of Um Habibah to the Prophet), and facilitated the migrants’ return journey.

In gratitude, the Prophet declared Axum a “favored land.” Many years later, when news of Al-Najashi’s passing reached Madinah, the Prophet honored the Christian king with a Muslim funeral prayer. Today, Ethiopia is about 35% Muslim. The eastern city of Harar, or “City of Saints” in Arabic, is often referred to as the fourth holiest city of Islam owing to its many mosques and shrines dating back to the tenth century.

Ethiopia and the Red Sea Region Today

Ethiopia’s current status as a host country for millions of refugees hailing from across East Africa and the Red Sea region echoes the First Hijra story. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as of June 2021 there were nearly a million registered refugees and asylum seekers in the country, making it the third-largest host in Africa and tenth worldwide. For a reference of comparison, the United States accepted 0 Yemeni refugees during the 2021 fiscal year and only 50 during the Trump years. By contrast, Ethiopia has hosted more than 3,000 Yemeni refugees since 2015 and continually welcomes more.

Furthermore, in January 2019 Ethiopia’s parliament passed one of the most integrative refugee laws in the world. While the law has yet to be comprehensively implemented—due in part to challenges at the institutional level in the run-up to the current war—its provisions grant refugees property rights, recognition of their degrees and certifications from their home country or previous country of residence, the right to attend school and work, freedom of movement, and more expansive eligibility for asylum.

The First Hijra represents the legacy of interreligious and interethnic respect both within Ethiopia and among its indigenous peoples, as well as for those beyond its borders. The story therefore presents a precedent that is not just helpful to resolving the current domestic conflict, but also speaks to how and why a peaceful Ethiopia could be an anchor of social and political justice for all of Africa and the Middle East: overcoming divisions to forge genuine political solidarity is the only way to build people power strong enough to bring about justice. When people are pitted against each other on the basis of religion or ethnicity, or any other identity grouping, it makes a region or country continually vulnerable to elite agendas, warmongers, and extractive foreign interests.

The Yemen War and the Ethio-Yemeni Migrant Community

Unfortunately, the people of Yemen are all too familiar with this equation. Yemeni refugees number around 3,000, but they are part of a larger blended migrant community including Ethiopian nationals who repatriated with their Yemeni-citizen children, spouses, friends, or relatives. Since the beginning of the war in Yemen, the International Organization for Migration has evacuated tens of thousands of Ethiopian nationals from the conflict zone. This population includes recently arrived migrants heading for Saudi Arabia overland, as well as thousands of Ethiopian nationals who were longtime residents of Yemen.

A photo from the early Ethiopian evacuation missions during the Yemen War shows piles of suitcases, a testament to the settled lives that so many had to leave behind.

Over the past three years, I interviewed over fifty Yemeni refugees and Ethiopian returnees residing in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa. While interviews usually started by addressing migration experiences, economic challenges, and bureaucratic hurdles to accessing services, they always wandered toward thoughtful conversations on opportunities for intercultural understanding and unity. Yemeni refugees mentioned the hospitality and acceptance of the Ethiopian people, while Ethiopian returnees spoke nostalgically about the quiet safety and general quality of life they experienced in pre-war Yemen.

Many interviewees then broadened their reflections to regional and deep historical analyses: If the precarity and opportunism of war deepens every type of fanaticism and intolerance, how can Yemen heal? What is the vision for a liberated and unified Yemen, and what role might religion and culture play in that future? How did many faiths and peoples live together in past eras, when Arabia was home to equal numbers of indigenous Christians, Jews, and Muslims?

The special relationship between Ethiopia and Yemen is an ancient one extending back nearly a millennia before the revelation of the Holy Quran, to the time of Prophet Sulayman and the Queen of Sheba. In fact, at the height of Axumite power, Yemen was most likely a province of the African kingdom. All of this history was common knowledge to the majority of my interviewees of every educational background. In one meandering afternoon of chewing qat with a North Yemeni refugee elder and his Ethiopian returnee wife, we might cover Najran, the Himyarites, Surat al-Fil, the First Hijra, Oromo identity politics, and the 1977 Red Sea “quadripartite summit” in Taiz. Based on this rich shared history, one interviewee even recommended that Yemen seek membership in the African Union.

Nearly all interviewees who had been in the country for more than a year concurred that Ethiopia’s multifaith national identity provides a compelling model for coexistence in Yemen. In reality, religion is already a complex and intimate vehicle for solidarity and belonging; there are converts to both Islam and Christianity among refugees and returnees. A small group of Yemenis host a Bible study in Arabic every week; some participants identify as converts to Christianity, while other attendees join the sessions out of a desire to better appreciate the religious beliefs of their Christian neighbors and colleagues in Addis Ababa.

The Larger Vision for Peace

In response to the Muslim travel ban imposed by the Trump administration, such organizations as the Arab Resource and Organizing Center in San Francisco rallied around the migration justice call: “Freedom to Stay, Freedom to Move, Freedom to Return, Freedom to Resist.”

For Ethiopian lawyer Abadir Ibrahim, the Hijra to Abyssinia exemplifies this call. Referring to Ethiopia as “the birthplace of the Hijri model of migrant rights,” Dr. Ibrahim underscored the model’s “deep symbolic significance” to both Ethiopians and Yemenis, as evidenced by its “positive impact on the lives of migrants on both sides of the Red Sea.” He elaborated: “Packed in that history one finds discourses and values connected with justice, liberty, and nondiscrimination; the freedom of thought, religion, expression, and association; due process rights; and the rights of refugees to a hearing and to social services. Due to their historic and symbolic significance, these were values that easily found a home in Dimtsachin Yisema, a Muslim-based grassroots human rights movement in Ethiopia that was widely supported by the North American Ethiopian Muslim community.” (Note: Islamic Horizons previously covered Dimtsachin Yisema in its September/October 2018 issue.)

The interrelationship between migrant justice and domestic civil liberties described by Ibrahim gets at the core of how the First Hijra can open up our political imagination to global prospects for justice. The word democracy has become hollow in our times, but the national imperative, described as follows, transcends terminology: to establish universal assurances that the core interests of diverse groups are secure, regardless of electoral turnover between various formations of the political elite. As one of the most diverse and multilingual democratic federations in the world, the only country in Africa that was never colonized, and a leading host of refugees and asylees, Ethiopia can, and must, find a pathway to sustainable peace—for the sake of the Ethiopian people, the larger Red Sea region, and the world.

In the Footsteps of the First Muhajirun: Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia

Three historic mosques in the Horn of Africa chart the path of the first group of Muhajirun: Eritrea’s Sahaba Mosque, Ethiopia’s Al-Najashi Mosque, and Somalia’s Mosque of the Two Qiblas.

The Sahaba Mosque, located in the town of Masawa on the Red Sea coast, was built adjacent to the famous ancient port of Adulis, where the Muslim refugees likely landed. In fact, many consider it the world’s oldest mosque. There is some uncertainty, however, as to whether or not it predates the Quba Mosque on the outskirts of Madina.

The current structure is of later construction and now in disrepair, but the mosque retains its original qibla facing Jerusalem. Prayers are still held there occasionally, of course, with the worshippers facing the Kaaba in Makka.

From the coast, the Muhajirun traveled about 190 miles (305 kilometers) southwest to Negash in current-day Ethiopia. The Christian Axumite king presumably permitted them to settle in that area, about 125 miles (201 km) east of his capital city, Axum. Axum is a sacred place for Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Christians, who believe that the Ark of the Covenant remains in its oldest church. Both Axum and Negash are in Tigray, one of the country’s eleven ethnic states.

Negash is therefore widely recognized as the Muhajirun’s first settlement, as evidenced by the excavation of a local seventh-century cemetery. The name of the local mosque, Al-Najashi, is the Arabic transliteration of “Negus,” which means “king” in ancient Geez. The king who hosted the Muslim refugees is buried within the mosque’s compound, as are several of the Sahaba who remained in Ethiopia.

Most of the Muhajirun returned to Arabia to rejoin their community and then relocated to Madina; however, a small group settled in Zeila, one of the northernmost towns in contemporary Somalia. There, they found a home with the local Somali Dir clan family and together constructed the Mosque of Two Qiblas in 627. Widespread conversion to Islam across the Somali region took place over the century following the mosque’s construction.

To honor the Dir clan, the tomb of Sheikh Babu Dena resides in the mosque. In keeping with other early mosques, the structure has two mihrabs: the first facing Jerusalem, and the second one facing Makka. Unfortunately, this mosque is now in ruins and is more of a historical landmark than a functioning house of prayer.

Preserving Heritage: Challenges and Achievements

In early 2018, the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency completed a multiyear restoration of the Al-Najashi Mosque for a very specific purpose: in July, Ethiopia and Eritrea signed a joint declaration of peace and reopened their shared border for the first time in decades, and Eritrean Muslims celebrated on the 10th of Muharram by holding a gathering in the thousands at the mosque.

Unfortunately, the mosque was damaged by shelling and reportedly looted during the current war. In December 2020, reports trickled out that Ethiopian and Eritrean troops were responsible for the damage. In an interview with BBC Amharic soon after, Abebaw Ayalew (deputy director of the Ethiopian Heritage Preservation Authority) stated that a professional team was on its way to document the damage to both the Al-Najashi Mosque and a nearby church and to chart a plan for repairs. He stated, “These sites are not only places of worship. [They are] also the heritage of the whole of Ethiopia.”

Indeed, one might argue that this mosque—as well as the two other early mosques highlighted above—are part of the spiritual heritage of Muslims worldwide. Perhaps in coming years the international ummah will fund the restoration of both the Mosque of Two Qiblas and the Sahaba Mosque, as Turkey did for the Al-Najashi Mosque.

The Legacy of the First Hijra in the United States

Meanwhile, diaspora communities commemorate the First Hijra’s significance worldwide. In 1986, Ethiopian Muslims established the First Hijra Muslim Community Center in Washington, D.C. Located on Georgia Avenue just a mile north of the nation’s preeminent historically black college, Howard University, this mosque has become an important part of Washington’s Pan-African landscape.

The website of the foundation that established the community center explains the significance of its name:

“The meaning and the significance of ‘Hijra’ is embodied in the Islamic calendar. Since its inception, the Islamic calendar represents a history of perpetual struggle between truth and falsehood, freedom and oppression, light and darkness, and between peace and war. The migration to Ethiopia and generous offer of political asylum to the oppressed companions of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) was the birth of freedom of expression and beliefs, whereas the Second Migration of the Prophet Muhammad to Madinah celebrates the end of oppression.”

An edited version of this article was published in the March/April 2022 issue of Islamic Horizons.

https://issuu.com/isnacreative/docs/ih_march-april_22?fr=sZTI0MzI0NzY3Mw

References:

Abdul-Rahman, Muhammad Saed, trans. 2009. Tafsir Ibn Kathir Juz’ 16 (Part 16): Al-Kahf 75 to Ta-Ha 135, 2nd ed. London: MSA Publication Ltd. (The section on Surat Maryam discusses the al-Habash [p.34].)

Abu Huzaifa. n.d. “Negash, Ethiopia.” IslamicLandmarks.com. https://www.islamiclandmarks.com/various/negash-eithiopia.

“Migration to Abyssinia.” 2022. Madain Project. https://madainproject.com/migration_to_abyssinia.

“IOM Evacuates 250 Most Vulnerable Ethiopian Migrants from Yemen.” 2016. ReliefWeb, March 15, 2016. https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/iom-evacuates-250-most-vulnerable-ethiopian-migrants-yemen.

Insoll, Timothy, and Ahmed Zekaria. 2019. “The Mosques of Harar: An Archaeological and Historical Study.” Journal of Islamic Archeology 6, no. 1 (2019): 81–107. https://doi.org/10.1558/jia.39522.

Girmachew Adugna. 2021. “Once Primarily an Origin for Refugees, Ethiopia Experiences Evolving Migration Patterns.” Migration Information Source, October 5, 2021. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/ethiopia-origin-refugees-evolving-migration.

“UNHCR Ethiopia Fact Sheet, June 2021.” 2021. ReliefWeb.com, July 19, 2021.

https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/unhcr-ethiopia-fact-sheet-june-2021.

On the new refugee law: Maru, Mehari Taddele. 2019. “In Depth: Unpacking Ethiopia’s Revised Refugee Law.” Africa Portal, February 13, 2019. https://www.africaportal.org/features/depth-unpacking-ethiopias-revised-refugee-law/.

“About Us.” n.d. First Hijrah Foundation. https://firsthijrah.org/our-work/.