Voices from the Sylff Community

Sep 28, 2017

Environmental Geopolitics in the Anthropocene: Understanding Causes, Managing Consequences, Finding Solutions

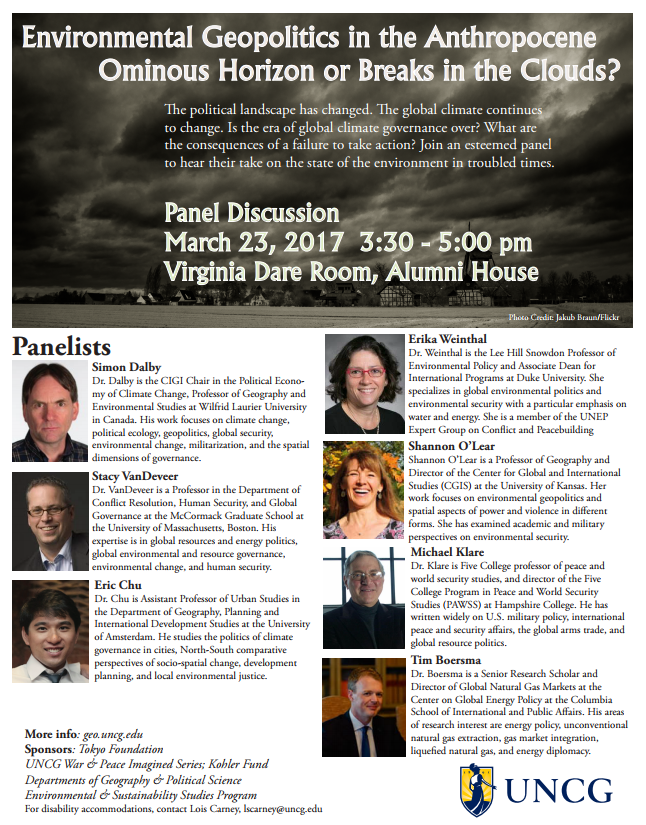

An SLI forum organized by University of Oregon Sylff fellow Corey Johnson, currently associate professor and head of the Department of Geography at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, brought together a group of policy-minded academics on March 22–24 at Greensboro. Experts specializing in such fields as the economy, security, geography, and energy policy discussed the best governance for sustainable development under the current circumstances, where solutions remain uncertain to the environmental challenges of global warming and the drain of natural resources. The public symposium that was conducted as part of the forum also attracted many students and citizens. A copy of the panel poster for the public discussion can be downloaded at the following link: https://geo.uncg.edu/wp-content/themes/Geo/assets/Panel-Poster.pdf.

***

Background

In recent years, the international political community has come to take more seriously the challenges of global increases in resource consumption, climate change, and sustainable development. The adoption of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement on climate change mark important milestones in multilateral commitments to making progress on these issues. However, as Brexit in Britain and the election of a populist-nationalist president in the United States suggest, the center of gravity of leadership on the most pressing global issues of the day—foremost among them environmental change—is shifting, perhaps irrevocably, away from the transatlantic alliance. This is happening at a crucial moment in time when coordinated leadership, foresight, and evidence-based policy are required if the planet is to not only avert the profound impact that climate change will have but also manage the geopolitical upheavals that can increasingly be linked to environmental change.

The forum “Environmental Geopolitics in the Anthropocene: Understanding Causes, Managing Consequences, Finding Solutions” brought together a group of policy-minded academics to delve into the convergence of these momentous environmental and political trends. Our goal was to better understand the causes and consequences of, and possible solutions to, some of these mega-challenges in the face of much uncertainty in the spaces of governance where resolute decisions will be required.

Events Overtake Good Intentions

When I proposed this forum to the Sylff Leadership Initiatives grant program in spring 2016, the United States was in the midst of an unprecedented presidential race. It was growing clear that the nominees of the two major parties would be Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. Like many observers, I thought it highly unlikely that Trump—with his unorthodox views on the issues to be addressed by the forum—would actually be elected to the most powerful office in the land. My working assumption at the time was that by spring 2017, when the forum would take place, there would still be plenty of debate over the ambitions and technical details of the Paris Agreement but the United States would still be a party to it and would lead efforts to mitigate climate change as the country that has emitted more greenhouse gases to the earth’s atmosphere since 1850 than any other.

Instead, when we met in March 2017, the forum participants were faced with a confusing and deeply unsettling landscape. President Trump campaigned on a platform that included very vocally dismissing international institutions and agreements including the United Nations and the Paris Agreement. Not surprisingly, given his dismissal of climate change as a “Chinese hoax,” he has since announced the government’s intention to withdraw from Paris, effectively ceding leadership on climate change to other countries, especially China.

In proposing the forum, I noted the huge gaps between the lofty rhetoric of multinational agreements, on the one hand, and our rather thin understanding of the best governance pathways to achieve sustainable development and climate change mitigation, on the other. I also noted that not only was environmental change—which has always played a role in geopolitics—accelerating, but a number of important geopolitical developments in recent years could at least in part be tied to environmental events. The upheavals across North Africa and the Middle East since 2011 are just the most visible of what is a broader set of realities about global geopolitical dynamics, namely that there are feedback loops between human-caused environmental changes and political events, and these relationships are not particularly well understood.

The Time-Scale Problem of the Anthropocene

Even as political winds shift and policy priorities change in the short term, the longer-term challenges of the unbending curve of growing resource consumption, a hotter planet, and the unsustainability of how economic growth has historically been achieved remain as vexing as ever. It is abundantly clear that the very health of the planet and of humankind hinges on our ability to successfully address the problems of constrained natural resources in an epoch where humans are themselves a serious geophysical force. The forum was framed by considering geographic and temporal scales together, and the following assumptions informed and provided material for further discussion:

Even as political winds shift and policy priorities change in the short term, the longer-term challenges of the unbending curve of growing resource consumption, a hotter planet, and the unsustainability of how economic growth has historically been achieved remain as vexing as ever. It is abundantly clear that the very health of the planet and of humankind hinges on our ability to successfully address the problems of constrained natural resources in an epoch where humans are themselves a serious geophysical force. The forum was framed by considering geographic and temporal scales together, and the following assumptions informed and provided material for further discussion:

- Humans have the now-unmistakable ability to act as a destructive geophysical force, creating what many scholars have described as a new geological era called the Anthropocene. In terms of climate change, this new era was roughly two centuries in the making; many of those who contributed to it are no longer living, and many who will face its consequences have not yet been born. Due to the complexity of earth systems and the forces that affect them, there is often a considerable time lag between the human activities that create the problem and humans’ ability to perceive the changes.

- There is a perennially vexing governance difficulty in making hard decisions in the short term about such issues as resource consumption and models of economic growth that might be required to reduce the potentially catastrophic long-term impacts of climate change, especially when the impacts are predicted rather than occurring. The same difficulty could be said to apply to governance decisions around geo-engineered solutions, given the potential for massively screwing up earth systems through human intervention.

- There is considerable geographic variation in the type and intensity of the effects of climate change, as well as in the types of institutions, governments, nonstate actors, and so forth that can play a role in addressing the effects. The governance landscape is highly uneven, and global regimes continue to be fragile and ill equipped.

All Doom and Gloom?

As academics we are accustomed to identifying problems, lamenting how they came to be, bemoaning how not enough is being done to address them, and then moving on. While this forum and the contributed papers had their share of this, the participants were also able to think about possibilities for future developments that give at least some cause for optimism. The Anthropocene, as Simon Dalby pointed out in his paper, is at its root the result of the “fire species” of humans manipulating, managing, and, above all, burning available resources to such an extent that any assumption of “geographic and geological stability as the background to the human story” must be discarded. Shaping the Anthropocene, which is now reality, requires a set of political choices that more intelligently seeks not just to reduce carbon combustion but also to reconfigure land use, urbanization patterns, and other aspects of human existence with changed earth conditions as the new baseline. Understanding that the global economy is a geological phenomenon requires what many, but not nearly enough, states and corporations have recognized: how capital is invested a more proactive accounting for how it contributes to environmental change.

There were numerous synergies between Simon Dalby’s intervention on the “geological turn” in Anthropocene geopolitics and Stacy VanDeveer’s governance strategies and mechanisms for reducing the material throughput of our economies. The Anthropocene, as many observers have pointed out, is an era during which the material footprint of the human species on the planet is more than appreciable to the point of being system altering. VanDeveer suggests that governance responses should seek to effect long-term reductions in consumption patterns through a variety of tools, including tax and subsidy changes, binding policies, certification and labeling, research, and normative transformation. While recent history has shown that humans are not particularly adept at sacrificing in the short term for longer-term benefits, there are examples where—given the right incentives and framing—longer-term, enlightened thinking can prevail.

Indeed, being open to the types of thinking that can “make it otherwise,” to cite participant Shannon O’Lear’s paper, will be necessary. Part of the shift in thinking that is needed among policy makers involves moving away from the assumption that isolated case studies are somehow representative and instead incorporating multiscalar analysis of connections between and among places and processes. Land acquisitions, common in Sub-Saharan Africa as well as in Middle America and elsewhere, are not just local events but rather reflect global capital flows and consumption habits. Much in line with Simon Dalby’s suggestion of laying out Anthropocene political choices much broader than simply in terms of how much CO2 we emit, O’Lear argues that knowledge production needs to take more seriously what forms of new knowledge are required to deal with Anthropocene realities. The framing questions take on additional significance in this respect.

Even before the strange turn of politics in the United States, it was clear all along that transitions of the massive energy system that fuels economic activity and daily life in much of the world would be incremental, not sudden. The case of natural gas illustrates this element of environmental geopolitics in the Anthropocene: is there a role for the lesser of fossil-fuel evils moving forward? Tim Boersma walked us through the role of gas in energy transition pathways in various parts of the world and offered his thoughts on the oft-heard trope of gas as the “bridge” or “pathway” fuel. Undoubtedly, for a variety of reasons—fracking, perceived environmental benefits vis-à-vis coal and petroleum, easier mobility of gas thanks to liquefied natural gas—natural gas has assumed a greater share of the world’s energy use in recent years, and that is expected to rise. But from an environmental perspective, the “bridge” needs policy in place for there to be an opposite side that is not simply burning more gas. In non-OECD countries, policy makers will seek a greater role for gas not only as a means of meeting climate goals but also for the shorter-term reason that gas is preferable in addressing atrocious air quality. Historically in Europe and North America, gas was first and foremost an urban fuel due to the infrastructure required to make it economically viable, and this can be expected to be the case in fast-growing places in the Global South as well.

As suggested by several authors, Anthropocene geopolitics requires an acknowledgment that change is already happening, and policy makers must incorporate adaptation strategies alongside well-intentioned efforts to mitigate further change. As a growing body of scholarship suggests, environmental governance happens in multilevel, polycentric fashion, with cities and subnational jurisdictions assuming an ever-increasing role. Eric Chu illustrates in his paper the ways in which cities can be more responsive and innovative as well as sensitive to local specificities related to the challenges of environmental change than can larger-scale governments. Through transnational municipal networks, cities can also share best practices and raise awareness. At the same time, Chu reminds us that there are some pitfalls in what he calls “methodological cityism,” in that there are substantial political, institutional, and scalar constraints to cities enacting progressive environmental policies. Facing such issues as sea level rise and climate-induced migration will require a multilevel set of responses that must include, but not be limited to, cities.

Conclusion

The Anthropocene is not an “environmental problem.” It is a human problem. It requires that we think systematically about, in the words of O’Lear, the possibilities of “otherwise.” This forum and what comes after represent a contribution to the rich debates happening in many places about what an “otherwise” might look like and how it might be achieved. This is not to understate the hurdles in the way of such change, which are substantial. But in this time of considerable political, economic, and social flux, it is entirely possible that the present is an opportunity to think outside the box and to shift our mindset into the Anthropocene.

Panelists of the Forum

Simon Dalby, CIGI Chair in the Political Economy of Climate Change and Professor of Geography and Environmental Studies, Wilfrid Laurier University

Stacy VanDeveer, Professor in the Department of Conflict Resolution, Human Security, and Global Governance, McCormack Graduate School, University of Massachusetts

Shannon O’Lear, Professor of Geography and Director of the Center for Global and International Studies, University of Kansas

Eric Chu, Assistant Professor of Urban Studies in the Department of Geography, Planning, and International Development Studies, University of Amsterdam

Tim Boersma, Senior Research Scholar and Director of Global Natural Gas Markets at the Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia School of International and Public Affairs

Michael Klare, Five College Professor of Peace and World Security Studies and Director of the Five College Program in Peace and World Security Studies, Hampshire College

Erika Weinthal, Lee Hill Snowdon Professor of Environmental Policy and Associate Dean for International Programs, Duke University