Voices from the Sylff Community

Nov 16, 2017

An Almost Forgotten Legacy: Non-Aligned Yugoslavia in the United Nations and in the Making of Contemporary International Law

Arno Trültzsch is a Sylff fellow from the University of Leipzig. He is working on a dissertation to explore the former Yugoslavia’s non-alignment policy and movement and its impact on international norms, including international laws and major UN resolutions for humanitarian and peace-building efforts, between 1948 and 1980. In this article, Trültzsch discusses the essence of his findings and arguments.

***

Introduction

The title of my PhD project, “Non-Alignment Revisited: Yugoslavia’s Impact on International Law 1948–1980,” already indicates that the project is set on the crossroads of different disciplines and methods: global and local (i.e., Southeast European) history, international law, international relations, and intellectual history. My starting point was the rather well-known fact that, after its dismissal from the socialist camp in 1948, Yugoslavia became one of the instigators, main drivers, and pioneers of the so-called Non-Aligned Movement. Research on this global phenomenon of the second half of the twentieth century is still scarce and scattered along single issues, such as decolonization, economic history, and postcolonial topics. General accounts of non-alignment are either contemporary assessments from the 1960s to 1980s or standout research endeavors done in recent years.[1]

I want to contribute to this strain of research with a study of Yugoslavia’s role and impact on international law through its non-aligned policies. I therefore focus on the historicity of international law and its doctrines as expressions of specific social and political contexts, tied together by the discipline’s normativity and claim to provide a universal set of rules to international problems. I have drawn on important thinkers like Martti Koskenniemi, Bhupinder Chimni, and Hersch Lauterpacht. I also address (early) Marxist and Soviet theories of international law, as both are crucial for understanding the Yugoslav socialist perspective on international affairs and their law.

Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement

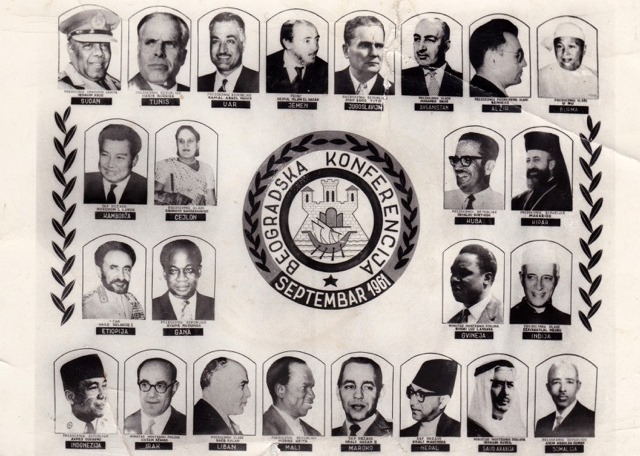

Commemorative poster for the first conference of non-aligned states held in Belgrade in 1961. Josip Broz Tito is fourth from right on the top row.

The Non-Aligned Movement first started as a loose dialogue platform and public forum of diverse smaller countries, especially former colonies from the Global South (Africa, Asia, and later also Latin America), who wanted to raise their voices against global inequalities and injustices and the ongoing nuclear arms race in the Cold War. Hence the name “non-alignment,” coined by India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, to describe the country’s independent foreign policy outside the forming camps of the northern hemisphere—the United States and its allies versus Soviet Union and its satellites.

After 1948, Yugoslavia was mostly isolated in a divided Europe, so the Yugoslavs looked for new allies, which they found among former colonies and mandate territories that had just gained their independence. During the 1950s and 1960s, therefore, Yugoslavian President Josip Broz Tito engaged in lengthy travels around the globe to build personal alliances with the leaders of these “new” countries. Tito’s personal diplomacy was widely publicized and praised, gaining Yugoslavia worldwide prestige. After an overture in 1956, during which he built a personal alliance with Prime Minister Nehru of India and President Nasser of Egypt, the first conference of the non-aligned countries was held in Yugoslavia’s capital of Belgrade in 1961.

Besides this high-level public diplomacy, Yugoslavia sought to strengthen the United Nations’ system for solving international conflicts, particularly through binding norms of international law, mostly to secure its delicate position in a divided Europe and globe. To that end, Yugoslav protagonists initiated an increasing number of draft resolutions within the organs of the United Nations, together with their new non-aligned partners—especially India and Egypt. Although many of these moves were connected with the complexities of Yugoslav foreign policy, they deserve thorough analysis and reassessment.

Evaluating the Legacy

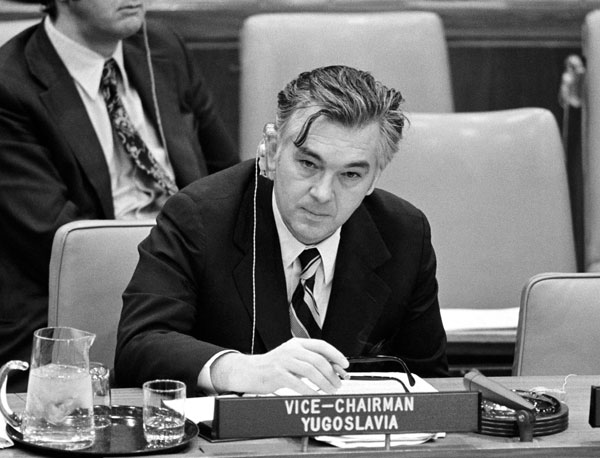

Milan Šahović, a legal expert of the Yugoslav delegation, speaking at the Fifth and Sixth Committees on legal matters of the UN General Assembly.

Milan Šahović, a legal expert of the Yugoslav delegation, speaking at the Fifth and Sixth Committees on legal matters of the UN General Assembly.

I am about to explore and question whether these initiatives contributed to an increasing legal certainty in international affairs and how they fitted Yugoslav foreign policy interests, especially in the controversial fields of human rights, peace and security, state responsibility, and disarmament. All these issues were discussed and redefined in the course of the Cold War, during which the non-aligned sought to be a “third” option of independent but cooperating countries outside the political camps and military alliances epitomized by the Warsaw Pact and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

In this vein, I am examining and evaluating specific Yugoslav approaches to and interpretations of international law, focusing on the triad of political actors, legal experts, and diplomacy. I combine this actor-based approach with the analysis of foreign policy documents—especially diplomatic correspondence and political reports between Belgrade and the UN delegations—and the critical examination of Yugoslav publications on international law. Another group of important sources are Yugoslav textbooks and studies dealing with different aspects and doctrines of international law and the UN system.

Likewise, a set of ideological and political treatises on non-alignment and Yugoslav socialism have caught my attention, as I try to highlight the connection between Yugoslav socialist ideology, legal expertise, and foreign policy initiatives in the United Nations. After 1948, Yugoslavia remained a socialist country (much to the surprise of the West) but outside the Soviet camp, soon developing a particular socioeconomic system and variant of Marxist ideology called “worker’s self-management,” which Yugoslav foreign policy even tried to popularize in some non-aligned developing countries, though to little avail.

Many of the pushes for a further juridification[2] of international relations did not necessarily result in so-called “hard” or codified international law. But I argue that these ideas still had a wider impact both on Yugoslavia’s international and self-image, especially in legitimating the authoritarian rule of its leader Josip Broz Tito and the League of Communists (the ruling party), and on the inner dynamics of the Non-Aligned Movement until the early 1980s. In my further research and writing process, I want to delineate whether these “image politics” were the primary purpose of Yugoslavia’s UN activities, or if they really had a tangible impact on international law.

I have therefore analyzed archive materials from the Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (which still keeps the Yugoslav records) and the Historical Archives of Yugoslavia, both of which are in Belgrade, for the period from 1948 to 1980. In the textbooks and in the archive files, I was able to specify a number of significant UN initiatives and their wider impact. Among these are important contributions for defining acts of aggression against other states that resulted in General Assembly Resolution 3314 (XXIX) in 1974 and the codification and elaboration of diplomatic and consular intercourse, leading to the 1964 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Law. Furthermore, Yugoslavia helped establish a general Magna Carta of international legal conduct in line with the political doctrine of “active peaceful coexistence”: the Friendly Relations Declaration of 1970, or Resolution 2625 (XXV). Likewise significant are Yugoslav drafts on counterterrorism measures (specifically, aircraft hijacking and protection of diplomats), leading to important conventions in 1972 and 1973.

Drawing on legal language, while seeking political solutions, Yugoslav UN diplomats and law experts repeatedly requested serious steps on disarmament, calling for a halt to the nuclear arms race, and supported the decolonization process as well as providing direct support for various postcolonial liberation movements, such as those in Algeria, Palestine, and South Africa. These actions led to the criminalization of apartheid and racism under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (adopted in 1965, entered into force in 1969) and the Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid (1973 and 1976). In the disarmament debate, meanwhile, only single issues could be tackled, and Yugoslav experts codrafted the conventions on prohibiting biological and chemical weapons. The former was opened for signature in 1972 and entered into force in 1975, while the latter reached these milestones in 1992 and 1993, respectively.

On the European scale, Yugoslav politicians, together with their colleagues from neutral Finland and Austria, mediated between the power blocs to establish a dialogue on peace, disarmament, and civil rights—the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE). Belgrade was the host city of the second summit in 1977. The Yugoslav drafts on national minority protection were incorporated into the CSCE framework and are still valid for the CSCE’s successor organization, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Minority rights were also an important field of action in the United Nations, but without the impact that Yugoslav proposals and concepts had on a European scale. Altogether, the country’s openness and affirmation of human rights stood in contrast to the country’s record at home; human rights were nominally intact but were focused on social and workers’ rights, and Yugoslav citizens could not enjoy the civil rights and freedoms that their country had officially recognized on an international scale.

While Yugoslavia is today remembered largely for the wars that resulted from the country’s dissolution eventually into seven states (if one counts Kosovo), which led to new legal problems on an international scale, the contribution of this socialist, non-aligned country to international matters and their law is largely forgotten—often even inside the successor states. I am about to change that, pending the completion of my dissertation (in German) hopefully by next year.

Further reading

For general information on and English abstracts and presentations by the author, see: https://uni-leipzig.academia.edu/ArnoTrultzsch

Trültzsch, Arno. “Blockfreiheit und Sozialismus: der Beitrag Jugoslawiens zur Völkerrechtsentwicklung nach 1945.” Die Friedens-Warte: Journal of International Peace and Organization 90, no. 1/2 (December 2015): 161–88. (in German)

———. “Völkerrecht und Sozialismus: Sowjetische versus jugoslawische Perspektiven.” In Leipziger Zugänge zur rechtlichen, politischen und kulturellen Verflechtungsgeschichte Ostmitteleuropas, edited by Dietmar Müller and Adamantios Skordos, 1st ed., 83–104. Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2014. (in German)

Arnold, Guy. The A to Z of the Non-Aligned Movement and Third World. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2010.

Kilibarda, Konstantin. “Non-Aligned Geographies in the Balkans: Space, Race and Image in the Construction of New ‘European’ Foreign Policies.” In Security Beyond the Discipline: Emerging Dialogues on Global Politics—Selected Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual Conference of the York Centre for International and Security Studies, 27–57. York: York Centre for International and Security Studies, York University, 2010.

Kullaa, Rinna. Non-Alignment and Its Origins in Cold War Europe: Yugoslavia, Finland and the Soviet Challenge. London: I.B. Tauris, 2012.

Mišković, Nataša, Harald Fischer-Tiné, and Nada Boškovska, eds. The Non-Aligned Movement and the Cold War: Delhi–Bandung–Belgrade. London, New York: Routledge, 2014.

[1] Significant recent publications on the general history of the Non-Aligned are: Jürgen Dinkel, Die Bewegung Bündnisfreier Staaten: Genese, Organisation und Politik (1927–1992), first ed. (München: DeGruyter Oldenbourg, 2015) (in German); Nataša Mišković, Harald Fischer-Tiné, and Nada Boškovska, eds., The Non-Aligned Movement and the Cold War: Delhi–Bandung–Belgrade (London, New York: Routledge, 2014); Guy Arnold, The A to Z of the Non-Aligned Movement and Third World (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2010); and, with a focus on Finland and Yugoslavia during the 1950s, Rinna Kullaa, Non-Alignment and Its Origins in Cold War Europe: Yugoslavia, Finland and the Soviet Challenge (London: I.B. Tauris, 2012).

[2] Juridification: turning moral ideas and political demands into written law; a wider term for codification, which more narrowly describes the written consolidation of laws that have formed out of custom or sheer practice, particularly in international affairs between two or more states.