Voices from the Sylff Community

Jun 27, 2019

Beyond the Treasures? Beyond the Nation? Museum Representations of Thracian Heritage from Bulgaria

Ivo Strahilov is a Sylff fellow from Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski.” His doctoral dissertation scrutinizes the social construction of the ancient Thracian heritage and its uses in modern Bulgaria. With the support of the SRA award, he visited Paris where he explored the making of three museum exhibitions of the so-called Thracian treasures. In this article Strahilov discusses some of his findings and suggests a direction for future debate.

* * *

Introduction: At the Margins of Europe

The notion of “Europe” alongside its territorial borders is not self-evident, nor coherent. One of the major uncertainties in this seemingly apparent concept is marked by the tension between the western and eastern parts of the continent. During the last decades, this problem has been investigated at length in academic literature, and several new analytical paths have been opened. Scholars have questioned both the cultural cultivation of the idea of Europe and its various regions, which are differently positioned on the symbolic geography around the prestigious core.[1] The Balkan Peninsula or Southeastern Europe, which also includes Bulgaria, represents a peculiar case in this regard. Recent critiques have delved into the historical role of “the Occident” in the “invention” of “Eastern Europe” as a specific category that is rarely recognized as truly European.[2] Other studies have outlined a hegemonic Western discourse that ascribes the Balkans to a zone of backwardness between “Europe” and “the Orient,” seeing them in a predominantly negative way and reproducing their stigmatization.[3] This, however, is not simply a foreign categorization; it is also shared by the people in such countries as Bulgaria, where this traumatizing lack of Europeanness equally functions as a self-perception. On the other hand, Balkan political and intellectual elites adapt themselves to this framework, manipulate it, and take advantage of their position in diverse situations and with varying goals. This is why some authors have also underlined that Balkan states have appropriated this understanding and even contributed to the reinforcement of the “otherizing” discourse and thus to the regionalization of the continent.[4]

Thrace as a European Heritage

This rather complex constellation is one of the starting points of my doctoral research. Examining the museological representations of the ancient past, I hypothesize that Bulgaria exploits the potential of cultural heritage to overcome its assigned position at the margins of “Europe.” To explore this assumption, I focus on the international exhibitions of the so-called Thracian treasures. These exhibitions have been organized by the Bulgarian state for more than 40 years in some of the most prominent museums all over the world, including India, Japan, Canada, the United States, Mexico, Cuba, Russia, and especially Western Europe. This project originated in the early 1970s, and since then it has been an indispensable instrument of Bulgaria’s national cultural diplomacy, which involves significant political and academic commitment.[5] Today it is deemed by some historians the most successful cultural product of Bulgaria. At the core of the project are ancient archaeological objects excavated within the territory of the present-day country. Many of them are made of precious metals and provoke strong interest both in professional circles and in the general public. The exhibited objects themselves are traditionally attributed to the Thracian tribes that inhabited the area of present-day Southeastern Europe in antiquity.[6]

In 2015, however, the fundamental premises of this project were reconsidered. During the preparation of the upcoming exhibition for the Louvre Museum in Paris, it became clear that the long-held concept and reading of the ancient past are becoming a subject of tense negotiations. The remaking of the exhibition’s narrative, which was produced through a dynamic Franco-Bulgarian collaboration, highlighted the complexities of setting a new mutually agreed interpretation of cultural heritage. Hence, I decided to pay particular attention to this exhibition in order to track the dynamics underlying the process of social construction of heritage. Thanks to the SRA award I was able to conduct fieldwork in Paris in 2018, where I interviewed museums curators, archaeologists, historians, and other experts. I also explored different institutional archives and media reports, and I contextualized them further through examination of previous studies available in specialized libraries.

Opening of the exhibition “Découverte de l’art Thrace: Trésors des musées de Bulgarie” at Petit Palais Museum (Paris, 1974). © Archives of Petit Palais Museum.

The concept of the Thracian exhibition is a heterogeneous phenomenon with many aspects, but here I would like to underline its presentation in a Western European context. As mentioned above, one of the hypotheses of my dissertation is that the Bulgarian state introduced this self-representational strategy and mobilized precious ancient objects to compensate for its marginal position on the continent. Thracian heritage, in this sense, is one of the usable concepts for the desired symbolic repositioning because it supposedly refers to Europe’s origins. To put it in a simplistic way, ancient heritage “europeanizes” Bulgaria retroactively.

The making of the exhibition at the Louvre in 2015, however, revealed for the first time that the heritagization of the Thracian legacy and its valorization abroad could entail serious turbulences. My findings suggested that discrepancies had occurred not only between Bulgarian and French (together with other foreign) scholars, but also within Bulgarian academia itself—between museologists, art historians and archaeologists, and between politicians, administrators, and scientists. Although the discussions and preparations resulted in a well-publicized exhibition accompanied by a conference and a representative catalogue including a significant number of authors and institutions,[7] it is worthwhile to revisit the representational logic that underlies the Thracian exhibition as a phenomenon. There is no doubt that the latter is an essential promotional tool for contemporary Bulgaria, but it also raises some questions.

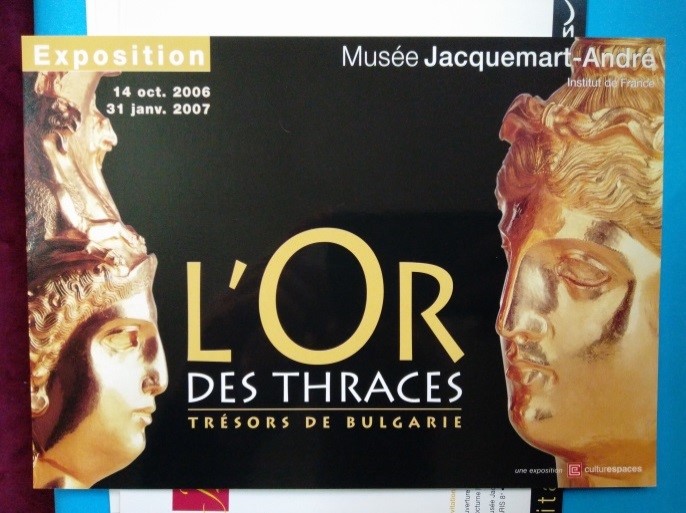

Promotional material of the exhibition “L’or des Thraces, trésors de Bulgarie” at Jacquemart-André Museum (Paris, 2006–2007). © Archives of Jacquemart-André Museum.

One of the questions comes from the fact that the Thracians’ legacy is spread across the territories not only of Bulgaria but also of neighboring countries—especially Romania, Greece, and Turkey. This is why their national historical disciplines have elaborated a rather ambivalent partnership on this issue.[8] Although with different intensity, they all research and popularize the Thracian past and thus transform it into a topical scientific problematic on a global level. The perimeter of their joint efforts is nevertheless restricted, and this limitation is exemplified by such exhibitions. The very act of an international presentation tends to legitimize a given national state as an heir of a certain legacy, and this is a well-known approach. A significant illustration here, captured in archival photos, is the Bulgarian national flag that covered the display cases in the museums during some inauguration ceremonies in the 1980s.

Heritage beyond the Nation?

Admittedly, organizing glamorous events abroad that promote the official image of a country is understandable and expected within the framework of cultural diplomacy. The point here is whether, after becoming a member of the European Union, Bulgaria (and other respective states) should maintain the same strategy driven by national interests. Would it not be more appropriate for political and academic authorities to enable transborder and transnational cooperation in terms of cultural relations that would demonstrate the richness and complexity of Thracian heritage? Hopefully, such an approach, which reconsiders archaeological practices and broadens the horizon of historical reading, would be a modest response to rising nationalisms. Thus, I would argue for a new multinational Thracian exhibition that would gather together scholars as well as precious collections of national museums in Southeastern Europe and beyond.

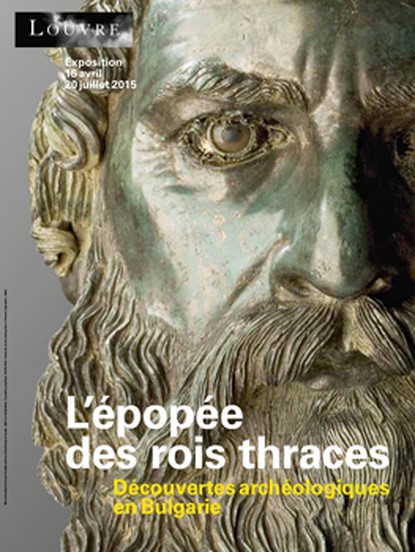

Promotional material of the exhibition “L’Épopée des rois thraces. Découvertes archéologiques en Bulgarie” at the Louvre (Paris, 2015). © Archives of the Louvre Museum.

While academic and governmental inflexibility predominates in terms of advanced cooperation, we are also witnessing new tendencies. For example, in 2018 an agreement was signed between archaeological museums in North Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Serbia that envisages a joint exhibition on the Necropolis of Trebeništa. The ancient site is situated in the Republic of North Macedonia, but due to complex and controversial historical developments it was excavated consecutively by Bulgarian, Serbian, and Macedonian archaeologists. Thus, the objects that were found have been dispersed in the three countries, and their interpretations have been incoherent.

Time will show whether this project will succeed in reconciling national historiographies and overcoming the restrictive representational narratives that traditionally accompany heritage. Yet it is already a sign of positive and needed change. Surely such a collaborative process will be slow and difficult; it will require concrete efforts and provoke shared uneasiness. But if we manage to take such a step, we will have a greater chance of developing a more constructive understanding of the territory we live in. After all, this is the territory in which we will have to face many new challenges; and making out of the past something that further divides us is definitely not relevant to the more acute economic, social, and ecological threats that affect our lives. On the other hand, if we leave aside the representational aspects of heritage, perhaps there would be room for a type of archaeology that would be engaged in a different way. Instead of being a tool that supports tight national agendas, it could be a bridge between them. Instead of delivering “treasures” for the tourist industry that deepens the gap between local people and elitist touristic imagery, it could be in service of some larger issues or specific environmental needs of the explored region itself. In sum, going back “down to Earth,” tracking the old answers and new questions that Earth contains will eventually help us to realize that the presentation of ancient heritage in seemingly stable national categories is possible but is only one of many options.[9]

[1] On the concept of “Europe” see Delanty, Gerard. 1995. Inventing Europe: Idea, Identity, Reality. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan.

[2] See, e.g., Wolff, Larry. 1994. Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

[3] See, e.g., Todorova, Maria. 2009. Imaging the Balkans (updated edn). New York: Oxford University Press; Goldsworthy, Vesna. 1998. Inventing Ruritania: The Imperialism of the Imagination. New Haven and London: Yale University Press; and Bjelić, Dušan I., and Obrad Savić (eds). 2002. Balkan as Metaphor: Between Globalization and Fragmentation. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

[4] Mishkova, Diana. 2018. Beyond Balkanism: The Scholarly Politics of Region Making. London and New York: Routledge.

[5] The history of this exhibition is thoroughly presented and analyzed in Roumentchéva, Sofia. 2014. Exposer les Thraces. Les collections thraces de la Bulgarie. Politique d’exposition officielle à l’étranger de 1958 à 2013. Mémoire de recherche. Paris: École du Louvre.

[6] The chronological and territorial aspects are the subject of ongoing academic debates. A recent overview of the question about the Thracians is available in Valeva, Julia, Emil Nankov, and Denver Graninger (eds). 2015. A Companion to Ancient Thrace. Wiley-Blackwell.

[7] Martinez, Jean-Luc, Néguine Mathieux, Alexandre Baralis, Milena Tonkova, and Totko Stoyanov (eds) 2015. L’épopée des rois thraces: Des guerres médiques aux invasions celtes 479-278 avant J.-C. Découvertes archéologiques en Bulgarie. Paris: Musée du Louvre/Somogy éditions d’Art.

[8] Marinov, Tchavdar. 2016. Nos ancêtres les Thraces. Usages idéologiques de l'Antiquité en Europe du Sud-Est. Paris: L’Harmattan.

[9] Part of this conclusion has been inspired in a certain way by Latour, Bruno. 2018. Down to Earth: Politics in the new climatic regime (translated by Catherine Porter). Cambridge: Polity Press.