Voices from the Sylff Community

Jul 12, 2019

Listen to Your Uber Driver: A Comment on the Economic and Emotional Vulnerability of Uber’s Silent Partner

With the support of the SRA award, Emma McDaid, a 2017 Sylff fellow at the UNSW Business School, carried out her doctoral dissertation research concerning “sharing economy” through interviews of Uber drivers on active duty in Europe. In this article, McDaid shares her research findings as well as her personal experience and viewpoints on fieldwork.

* * *

With the advent of sharing organizations, or platforms, like Uber and Airbnb, consumers and entrepreneurs have inherited more choice and flexibility. Sharing marketplaces are disintermediated, meaning that they operate without a middle partner, so information is shared by individuals online in a reciprocal fashion when they leave star ratings or reviews on their peers. As accounting scholars, we have been busy investigating the impact that such online ratings and rankings (the TripAdvisor ranking index and Amazon product ratings, for example) have on traditional notions of accountability and, indeed, how these mechanisms are responsible for a new audit society—an era heralded by a heavy focus on the verification of lived experience. However, a small number of us are also beginning to address how these metrics are used by organizations to manage platform users. For example, Uber drivers must maintain a customer rating of 4.6 stars (out of a possible 5 stars) in Sydney, Australia, if they want to maintain job security. A rating lower than this and “deactivation,” or dismissal, occurs. Hence, for these drivers, a 3-star rating often means the difference between being employed and being unemployed. In my research, in addition to conducting research in Australia, I have been able to travel overseas with the help of the Sylff travel scholarship to investigate how the rules of platform organizations affect the service providers who hold a key position in the value chain.

With the advent of sharing organizations, or platforms, like Uber and Airbnb, consumers and entrepreneurs have inherited more choice and flexibility. Sharing marketplaces are disintermediated, meaning that they operate without a middle partner, so information is shared by individuals online in a reciprocal fashion when they leave star ratings or reviews on their peers. As accounting scholars, we have been busy investigating the impact that such online ratings and rankings (the TripAdvisor ranking index and Amazon product ratings, for example) have on traditional notions of accountability and, indeed, how these mechanisms are responsible for a new audit society—an era heralded by a heavy focus on the verification of lived experience. However, a small number of us are also beginning to address how these metrics are used by organizations to manage platform users. For example, Uber drivers must maintain a customer rating of 4.6 stars (out of a possible 5 stars) in Sydney, Australia, if they want to maintain job security. A rating lower than this and “deactivation,” or dismissal, occurs. Hence, for these drivers, a 3-star rating often means the difference between being employed and being unemployed. In my research, in addition to conducting research in Australia, I have been able to travel overseas with the help of the Sylff travel scholarship to investigate how the rules of platform organizations affect the service providers who hold a key position in the value chain.

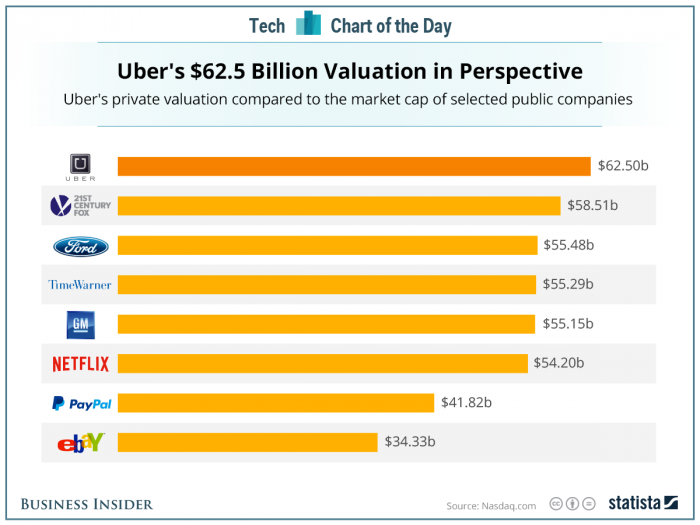

The Uber organization reflects a new kind of disaggregated labor market, accessible to its users through a technology application on a mobile device. It is the largest of the ride-sharing model, holding over two million drivers in partnership around the world. With Uber, the users are passengers who request a ride (consumers) and drivers who have the time, skill, and vehicle to provide the service (service providers). Physically, Uber’s service providers are globally distributed, rarely coming face to face with a manager in any centralized hub or factory floor; the nature of work also means that they rarely come face to face with each other. Indeed, the courts continue to deliberate over whether these drivers hold the status of employee or contractor. Regarding this, Uber has argued from the start that its drivers are independent contractors, citing the drivers’ freedom to choose when they source work through the application and the legalities surrounding freedom of uniform and insurance requirements. However, drivers counterargue employee status based on the control that Uber sets over remuneration rates and the limitations surrounding a driver’s rights in choosing trips and accessing such information as trip destination. But while the contractor-employee debate rages on, the critical role that drivers play in the value chain for the Uber organization is sharp and definite. They are the key stakeholders responsible for the creation of economic value for the Uber empire. And this is a valuation that is continuing to rise; the organization was recently valued as the wealthiest privately owned company in the world, with its market capitalization at US$62.5 billion.

Source: Retrieved from Business Insider, December 2015, https://www.businessinsider.com/uber-valuation-vs-market-cap-of-publicly-traded-stocks-2015-12.

Their unique conditions of work prompted me to investigate how drivers were being managed by the organization. Data collection and analysis is ongoing in this regard, but in the following paragraphs, I outline some of the reflections that I have formed from my 2017 and 2018 data collection in Europe and Australia. These reflections are twofold: the first is with respect to conducting field research in these new technologically mediated and disaggregated workforces, and the second regards the most material challenges that I feel Uber drivers are currently facing.

Field Research and the Sharing Economy

I initially collected data in Australia from around the end of 2015. But in 2017, using my Sylff SRA, I left Sydney and arrived in London to conduct field interviews. From there, I traveled on to Paris and Copenhagen. The duration of my research abroad was four weeks in total, and I conducted ten formal interviews with Uber drivers, which supplemented the interviews that I had conducted in Australia. While in Europe, I also gathered a significant amount of data from drivers via phone and through online chat rooms. Although I had mapped out the field and my intentions for data collection, I found that the logistics surrounding field interviews of this type meant that my plans changed frequently. I had to be resourceful and at times imaginative so that I could conduct interviews. Most Uber drivers work perilously hard, and although many expressed interest in being part of my research, interview times were often restricted to moments when demand was low on the application. It was not unusual to have drivers cancel an interview because they had just been pinged through their device for a trip. It was also not unusual to interview drivers before the sun came up, in coffee shops in suburbs surrounding airports—where they might expect a surging fare to come about soon. In short, without the humdrum of everyday organizational life, the field researcher needs to be sensitive to a highly changeable environment, building a significant degree of flexibility into their data collection plans. This requires more perseverance in the field, but being agile in an environment like this can also be deeply rewarding. When successful, researchers are immersed in the participant’s natural lived experience and thus extract a richer ethnographic account of the field.

An Uber Driver’s Challenges

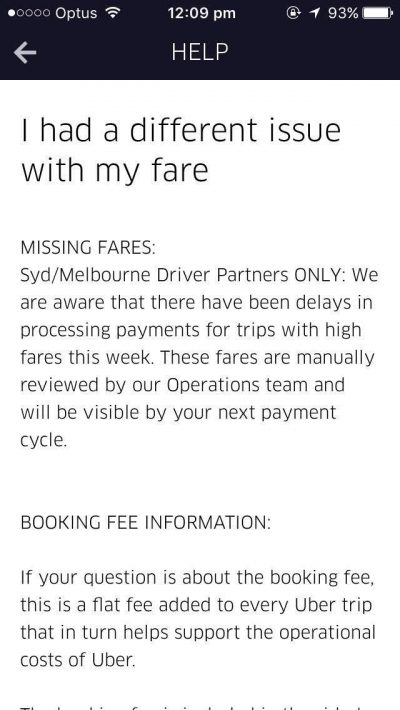

In conducting the interviews, it became clear that Uber drivers are facing a number of challenges. Changes to the minimum fare for a trip, accessing Uber personnel to resolve pay disputes, and defending themselves against customer complaints are examples of some of the more rigorous challenges. These challenges have both economic and emotional effects on drivers. For example, when Uber entered the French market in late 2011, the minimum fare that a driver could demand was approximately €20. Over the past number of years, this has dropped down to €6, marking a 70% reduction. And while advocates for the organization will likely insist that higher minimum fares were required in order to enter new markets, many drivers have become financially vulnerable after signing on with high expectations. Drivers can also be financially vulnerable in times when their pay is incorrect, is delayed, or fails to arrive in their bank accounts—common war stories that participants offered. In these cases, they reach out to Uber through the “Help” function on the application—essentially a chat bot—waiting up to five days for an adequate, non-system-generated response. An Australian driver provided an example of a standard response issued at times like this in the image below.

Unsurprisingly, drivers go through a range of emotions in respect to this treatment. A sense of frustration was commonly expressed. While they accept that the terms and conditions of operating as a driver can often change, these unilaterally imposed rules often change without warning and explanation. Drivers describe having little control other than to start and stop driving. Driver John* commented, “They call it a partnership; there’s no partnership,” while another, Driver Mike*, explained, “See, I’m just a number. I’m just a nobody.” The setting of prices or fares by the technology proved most frustrating, as drivers believe they personally incur costs that should be built into the fare. Driver Paul* described the logic as follows: “They just don’t get it. They have no idea what it costs to run a motor vehicle. To us, us guys who do it full time, it’s a business, a small business. . . . Ask us. Have a round table conference. What are your costs? How can you set base fares and not know what people’s costs are?”

Unsurprisingly, drivers go through a range of emotions in respect to this treatment. A sense of frustration was commonly expressed. While they accept that the terms and conditions of operating as a driver can often change, these unilaterally imposed rules often change without warning and explanation. Drivers describe having little control other than to start and stop driving. Driver John* commented, “They call it a partnership; there’s no partnership,” while another, Driver Mike*, explained, “See, I’m just a number. I’m just a nobody.” The setting of prices or fares by the technology proved most frustrating, as drivers believe they personally incur costs that should be built into the fare. Driver Paul* described the logic as follows: “They just don’t get it. They have no idea what it costs to run a motor vehicle. To us, us guys who do it full time, it’s a business, a small business. . . . Ask us. Have a round table conference. What are your costs? How can you set base fares and not know what people’s costs are?”

The drivers’ levels of take-home pay are inadequate, which is highlighted in an Australian government report that finds that their earnings fall short of the minimum wage (Stanford, 2018). This has led many people whom I have talked with to use metaphors of slavery when discussing the nature of platform work. And the use of technology as a tool to delegate terms and conditions on a platform does nothing to sooth the feelings of low self-worth that people doing this work experience.

These challenges exist for drivers in an environment where the customer’s voice has much more power than their own. Again, the Uber organization will say that customer complaints should be taken seriously, and indeed they should because of the nature of the service being sold. But drivers complain that their voices often go unheard when complaints are raised. At times like this, refunds are frequently and immediately given at the expense of the driver, and drivers are often deactivated from driving until they protest their rights. For this reason, many drivers now operate a dashcam in their vehicle—as a means to record trips and protect themselves in the event of an unfair complaint.

Dashcams are one of many responses to the position that drivers find themselves in. Other academic studies are reporting evidence that they have worked together to try to manipulate surge pricing by organizing mass deactivation, effectively gaming the technology (Mohlmann and Zalmanson, 2017), and that they continue to engage in strikes and efforts to join trade unions around the world. The precarious legal nature of the work is a problem faced by drivers fighting for change and for solutions to the challenges they face. In researching this field, it is hard not to empathize with their position. It is clearly one that belies the rhetoric often heard with regard to the sharing economy.

Conclusion

Uber has done great things for customer choice, achieving global disruption of an industry long considered the gold standard of secure economic sectors. Introducing competition has made transport more affordable and reduced unemployment rates. However, investment has fallen out of the taxi industry, with market value wiped from taxi plates in many major cities and reduced demand affecting that workforce. And taxi drivers have been vocal about these effects. But despite all the noise that Uber has created, it is important to be mindful of the challenges that are imposed on the Uber driver. We hear frequent hagiographic accounts of what it is like to “be your own boss,” in the media and in society in general, but less about the effects of working in these conditions. These are new industrial practices that use technology in new ways—creating, in effect, a new employee. Action in this regard may need to be taken if consumers want to responsibly enjoy the Uber service.

References

Mohlmann, Mareike, and Lior Zalmanson. “Hands on the Wheel: Navigating Algorithmic Management and Uber Drivers’ Autonomy.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2017), December 10–13, 2017.

Stanford, Jim. “Subsidising Billionaires: Simulating the Net Incomes of UberX Drivers in Australia.” Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute, March 2018.

*Names have been changed to preserve confidentiality.