Voices from the Sylff Community

Nov 22, 2019

REDD+ and the Forest Commons in Nepal

Sylff fellow Shangrila Joshi, a researcher on environmental studies and climate justice, held workshops and a forum on REDD+, one of the climate mitigation initiatives, for forest community users in Nepal, with funding from Sylff Leadership Initiatives (SLI). Although REDD+ is widely promoted as a global effort to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, Joshi argues that the implementation of associated projects often lacks informed consent by all stakeholders, and it is often the case that community forest users are left out from the discussion. Joshi conducted the SLI project to raise proper understanding of REDD+ among forest users with the ultimate goal in mind of realizing climate justice.

* * *

As climate change moves from being an impending crisis to an ongoing planetary emergency, it is important to critically evaluate the many so-called climate solutions that have arisen in response. REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) is one of the mitigation options that have emerged out of the United Nations deliberation process. It is a market-based mechanism to address climate mitigation by promoting the sequestration of carbon dioxide in forests while facilitating a global trade in certified emission reductions of sequestered carbon. This arrangement allows high emitters to meet their emission reduction targets by financing emission reduction programs in forest-rich developing countries.

Internationally, REDD+ has been heavily criticized and opposed by affected communities, scholars, and activists due to concerns about land grabs and human rights abuses and for not addressing the primary source of greenhouse gas emissions, namely fossil-fuel-based industries. Nepal has been an attractive prospect for those seeking to pursue these mitigation attempts while minimizing their worst side effects, because REDD+ has been proposed for community forests with a proven record of governance that empowers local communities while enhancing forest cover.

SLI Project Highlights

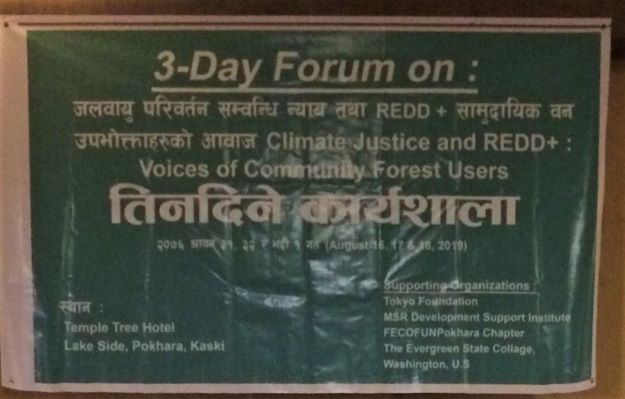

The perceptions of REDD+ among Nepal’s community forest users have been the focus of my research investigations for the past few years. Specifically, I interviewed forest users and conducted participant observation in the three sites in Nepal where the REDD+ pilot project was implemented—Gorkha, Dolakha, and Chitwan—during the monsoon of 2017. I conducted follow-up meetings and site visits in Chitwan in 2018. During August 2019, with SLI support, I facilitated a series of workshops in Chitwan and a three-day forum in Pokhara bringing together 24 members of the Community Forest User Group (CFUG) and Federation of Community Forestry Users Nepal (FECOFUN) from 12 districts of the Terai, where Nepal’s first World Bank program for REDD+ is slated for implementation.

Conversations in the workshops and forum revealed that while the desire of forest users to benefit from REDD+ is strong, their knowledge of how REDD+ specifically and carbon trading more generally operates in the local, national, and international contexts is weak. There is high demand for such knowledge to be widely disseminated in areas where REDD+ programs are to be ushered in. Participants were highly enthusiastic about welcoming REDD+ to their communities in ways that maximize economic and ecological benefits while avoiding harm to local communities. There was strong consensus among all participants that knowledge regarding REDD+ is highly inadequate in the local communities to be affected by REDD+, that access to such knowledge is desirable and necessary, and that any policies and benefit sharing should be equitable and just and involve meaningful participation of all stakeholders from the start. Community forest users at the forum and workshops overall expressed a strong desire to be active participants, not passive recipients in Nepal’s REDD+ programming.

Without a proper understanding among those who would be most affected by REDD+ of how REDD+ operates, how it strives to mitigate climate change, and how local forests and forest users are implicated, I argue that its proponents risk ignoring the principle of free, prior, and informed consent. The deliberations of the forum and workshops have been summarized in a white paper that has been shared with concerned officials in the Ministry of Forests and Environment, the World Bank, and FECOFUN, as well as media outlets in Nepal, so that the voices of community forest users may reach concerned authorities. In the white paper, I argued that meaningful participation and fully informed consent were not facilitated in all community forests in the Terai before the agreement on REDD+ was made between Nepal and the World Bank. If REDD+ is to move forward in Nepal, it is urgent that these gaps and oversight be rectified with a coordinated drive to involve local forest stakeholders in all REDD+ districts, through educational programs and discussion about the complex connections between climate change and forests, how REDD+ operates, what the rights of local forest users are, and how they can best advocate for their rights, if REDD+ is to move forward in Nepal.

Neoliberal Climate Solutions and the Commons

Although Nepal does not present blatant cases of disenfranchisement such as land grabs in areas where REDD+ projects are being introduced, concern is warranted for possible erosion of progressive structures. REDD+ is often characterized as a neoliberal solution, meaning it is predicated on the problematic assumption that free trade is the best way to maximize well-being and that the market is the best place through which to resolve social and environmental problems by virtue of the enlightened behavior of consumers buying and selling commodities. This is a decidedly different approach to resolving problems from that of members of a community deciding to impose rules and regulations to change behavior and address identified problems. Those interested in learning further about these two distinct ways to conceptualize and resolve problems may wish to look into the work of Elinor Ostrom, who tirelessly sought to correct the misconceptions introduced into the realm of environmental problem solving by Garrett Hardin through his highly influential yet problematic article “The Tragedy of the Commons.”

Is the tragedy of the atmospheric commons best solved through collective action—such as through a concerted global effort to scale back the burning of fossil fuels, addressing the problem at the source—or by commodifying the atmosphere, buying and selling carbon credits in the global marketplace? Carbon trading commodifies the atmospheric commons by assigning a price for a unit of reduced emissions: a carbon credit that can be bought and sold in the global carbon market. As a commodity, the price of carbon is determined not by its actual worth but rather by the vagaries of the market, and hence it is greatly underpriced. Ironically, the buyers of carbon credit—the ones creating emissions—determine the price of emissions reduction, while those who are already relatively blameless have little to no say. The latter are also more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, hence the importance of a climate justice lens to evaluate these neoliberal climate solutions.

Not only do those members of the global community who are making a carbon trade possible due to their labor and everyday choices have little power to influence the price of the carbon commodity they are selling; they are in many cases enabling this trade without their fully informed consent. Intermediaries such as the World Bank and government agencies often mediate the transactions between the buyers and sellers of carbon credits in ways that diminish the agency of the seller. Even if blatant instances of disenfranchisement may not occur in Nepal, these subtle ways of what geographer David Harvey calls “accumulation by dispossession” are concerning. In addition to these issues that are generic in the world, the stakes are high for Nepal also because of credible threats to common pool resource governance structures such as community forestry.

Community forestry users and leaders are generally highly welcoming and desirous of REDD+ projects due to the resources they promise, even if and perhaps precisely because the complex connections between forests, community forestry institutions, and global climate change are not well understood. The integration of local forests into a regime of global carbon trade requires quantification and measurement of carbon sequestered in forests in such a manner that privileges reductionist ways of managing forests. A related concern then is whether a move to embrace REDD+ might disenfranchise forest users from their ability to use their local and/or traditional ecological knowledge for forest management in ways that disproportionately privilege outsiders with technological skills and training in “scientific forestry.”

Power dynamics in the local context are important to understand as well. Specifically, programs such as REDD+ operate within an established culture of patriarchal domination, caste privilege, and disproportionate power of the urban educated elite. Attempts at gender sensitization and gender mainstreaming are laudable if insufficient, but there are indications that efforts to encourage equity for Dalit and Janjati groups are occurring in problematic ways that appear to further exacerbate animosity between social groups. If these instruments of carbon trading are to continue and do so in socially just ways, the question of what constitutes a “fair trade” in carbon as commodity at multiple scales begs serious attention.

The climate crisis can be seen as creating opportunities to reevaluate power dynamics at multiple scales, as well as to re-envision how the earth’s resources are used. Even as climate change offers new frontiers for the decades-long project of commodifying nature, thus enhancing the power of corporations, it has strengthened the resolve of activists who are striving to keep remaining fossil fuels in the ground and to hold companies and countries accountable for the climate crisis. In Nepal, there are opportunities to strengthen existing institutional arrangements designed to empower ordinary people to engage in ecologically sustainable behavior. The challenge is to do so equitably and in meaningful, not tokenizing, ways. The current moment in Nepal—and the world—serves as a reminder that the stakes for a battle between these competing forces have never been higher.

(All photos by Addison Joshi Felizola)