Voices from the Sylff Community

Apr 12, 2022

The European Citizens’ Panel on Democracy: An Opportunity for a Holistic Approach to EU Values

In this contribution, 2017 Sylff fellow Max Steuer presents his insight on the first session of the European Citizens’ Panel (ECP) on democracy, jointly organized in Strasbourg by the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union, and the European Commission in September 2021, which he attended as a “citizen participant.” He highlights a key risk as well as opportunities of the European Citizens’ Panels for developing a more robust and inclusive democracy in the EU.

* * *

The Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFoE) is a flagship initiative in deliberative democracy and experimentation. The Joint Declaration of the EU institutions organizing the CoFoE speaks about “open[ing] a new space for debate with citizens to address Europe’s challenges and priorities” that will generate authoritative conclusions by 2022, including on the potential needs for a structural reform of the EU. The European Citizens’ Panels (ECPs), of which there are four, are at the heart of the “experimental face” of the initiative: they provide randomly selected citizens with the opportunity to articulate their visions of the EU in a structured environment with the possibility for the outcomes to be taken seriously by policymakers.

While the impact of the expected conclusions from the CoFoE is uncertain, the ECPs can already be seen as a success from a symbolic perspective after the first sessions in September and October 2021; as the European Parliament was the venue for all four meetings, citizens replaced parliamentarians for a (very) short while and presented their ideas in the Strasbourg Hemicycle.

Based on my experience as one of the approximately 200 “citizen participants” of the ECP on democracy (second ECP), I argue that the key challenge ahead of the ECP is an approach to EU values that divides them into separate streams and limits the discussion about them as integrally connected and inseparable. On the bright side, three moments from the second ECP—where an alternative, holistic approach to EU values surfaced in a bottom-up fashion—point to the ECPs’ potential to foster EU democracy.

The start of the first ECP plenary session in the European Parliament Hemicycle in Strasbourg, September 24, 2021. All recordings of the plenary sessions are publicly accessible. (Photo: Max Steuer)

The Procedure in a Nutshell

The second ECP was set out to focus on “European democracy/values, rights, rule of law, security.” The title itself is puzzling, because the list of EU values, as defined in the Treaty on the EU (Article 2), encompasses “respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities”; hence, the rule of law and (human) rights are part of EU values, alongside democracy and others, rather than standing separate from them.

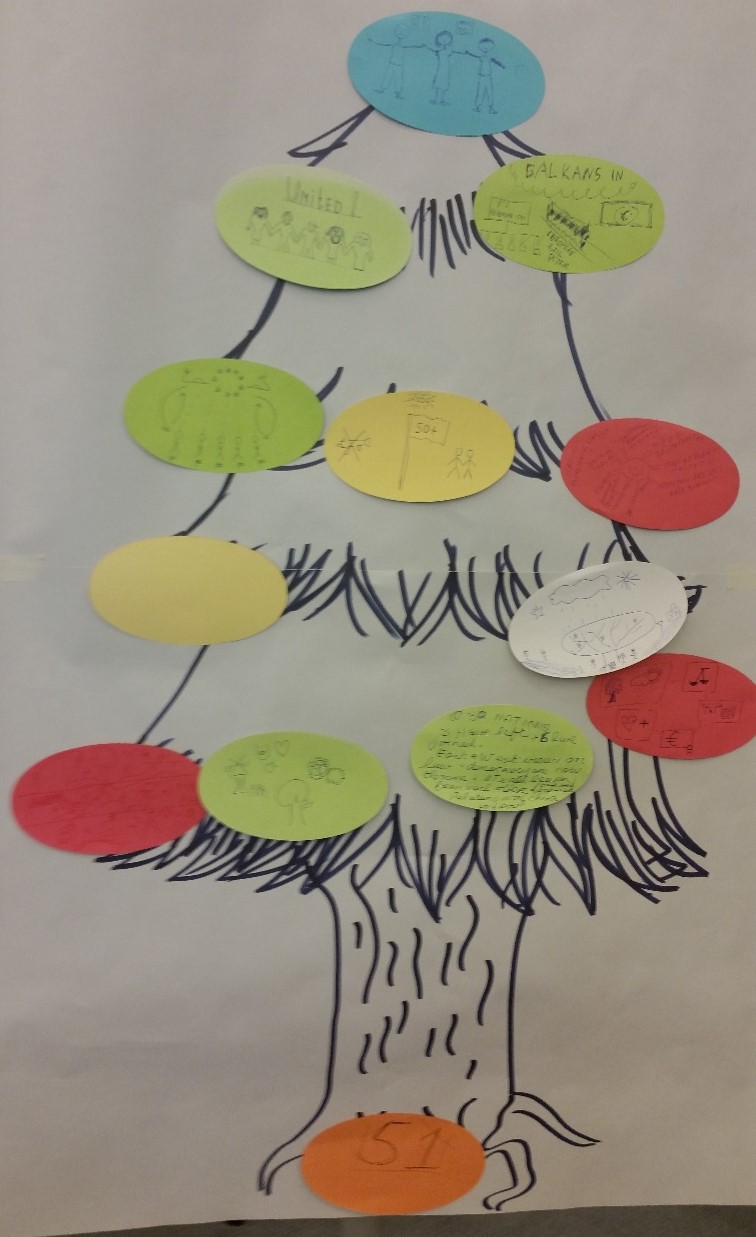

During the first session of the ECP, citizens were invited to articulate their visions of the EU in 2050 by drawing their “EU vision trees” and then “zoom in” on specific questions that they consider important to be debated during the subsequent sessions. Most discussions unfolded in working groups composed of around a dozen citizens. These were accompanied by a few plenary meetings introducing the session, which also included discussions with experts, and a final plenary devoted to approving several main topical “streams” to be addressed during subsequent meetings as they emerged from the “sum total” of the working group discussions.

Thus, the design of the sessions—and that of the ECPs more generally—was intended to work in a bottom-up fashion. The problem here is that democracy does not come with its exclusive pool of questions. All major questions on the EU’s future are also questions of democracy. Moreover, if “democracy questions” are not to be reduced to those of elections, they are integrally related to other EU values, including human rights and the rule of law.

Citizens were not constrained to engage with particular values while formulating the topics. Yet the limitations posed by the separation of individual values became apparent during the final plenary. Here, based on the citizens’ identifications of key questions, the moderators presented the key topical areas (called “streams”) for subsequent sessions. These, in the version voted and approved by the plenary of the panel, encompassed rights and nondiscrimination, protecting democracy and the rule of law, institutional reform, building European identity, and strengthening citizen participation.

A Key Challenge

As noticed by some citizens, questions categorized under human rights could equally be discussed under democracy, and vice versa. For example, the protection of human rights in the context of pandemic-induced restrictions is not merely a question of democracy, and gender equality is not merely a question of human rights. The danger in preparing neat “streams” is that connections between the topics become less visible and the final recommendations less informed.

One of the “EU vision trees” produced in the ECP working groups. Participating citizens were encouraged to place their visions near those of their fellow citizens that are most appealing to their own vision. September 25, 2021. (Photo: Max Steuer)

In addition to topical separation of EU values in the ECP discussions and emerging “streams,” the risk of failing to achieve a holistic approach to EU values stems also from the formal “eligibility requirement” that needs to be met in order to “have a voice” at the ECP: EU citizenship. The exclusivity generated by this requirement comes across as particularly pertinent when “democracy” is explicitly listed in the ECP’s title. In short, the CoFoE that sets out to address the future of Europe is not open to all Europeans. Even if accepting the (by no means obvious) assertion that the future of the EU can be debated between EU citizens on their own, the future of Europe as a continent is hardly limited to EU citizens, with other Europeans standing “on the outside” of democratic deliberations.

While there appear to be no easy solutions to this conundrum, one could potentially be found directly in Strasbourg. The Council of Europe brings together all Europeans (except the citizens of Belarus, whose plight clearly falls within the subject areas of this ECP). Yet there are virtually no signs of collaboration between the Council of Europe and the EU on the CoFoE. Inviting representatives of the Council of Europe, including those of the European Court of Human Rights, to interact with the conference participants could help foster knowledge about both institutions and emphasize their common goals. Furthermore, discussing human rights as sources of legal protections in Europe via an intertwined web of mechanisms and institutions could provide very useful impulses. Ultimately, an involvement of all Europeans, and not just EU citizens, is necessary for an inclusive debate on the future of Europe.

Another possible solution is specific to the five discussion “streams” as they have been approved for the second ECP. An increased focus on noncitizens could also have been part of their formulation. While migration is one of the main themes of the fourth ECP, it should not be absent from the ECP addressing EU values.

Three Signs of a Unique Opportunity and Potential

The impact of the second ECP on the discussions about democracy as an overarching basis for all ECPs remains to be seen. Challenges ahead encompass the capacity to foster holistic approaches to EU values and inclusive conversations. This does not require embracing the unity of value, but it does invite discussions that avoid “us” (EU citizens) versus “them” (everyone else without EU citizenship) dynamics.

Yet the first session of the second ECP still generated several particularly promising moments for a holistic, as opposed to fragmented, understanding of EU values. One is the connection between democracy and key societal issues that were not originally anticipated to be discussed by the second ECP—notably, climate change and socioeconomic development. Discussing climate change as a question of democracy, fundamental rights, and the rule of law might yield refreshing perspectives and facilitate bridges with the other three ECPs, reinforcing the impact of all of them on the CoFoE plenary.

Secondly, an emphasis on connecting economic security to democracy, understood as the possibility to effectively participate in public life, was added as a result of the “feedback round” to the thematic streams preceding the final plenary. This indication of a more democratic understanding of security may open the door for including security as a public good into the discussion on EU values and democracy, rather than seeing it as potentially justifying restrictions on fundamental rights that are the bedrock of democracy.

A third promising moment lies in the emphasis on education on democracy as a matter of EU values. As pointed out during one of the expert presentations, one is not born a democrat but learns to be one. Education as a tangible life experience of the ECP participants may raise awareness of the importance of free media and open communication, fostered by independent institutions, and encourage a “tree-like” perspective, much in the spirit of the “EU vision trees” drawn by the working group participants.

This post is an edited and abridged version of a contribution that appeared via Verfassungsblog.de, a major forum for debates on constitutionalism in Europe and beyond. Since its publication, the ECP on democracy completed its work in December 2021 with a series of recommendations that are currently being considered by the CoFoE plenary.