Voices from the Sylff Community

Rui Caria, a PhD candidate and teacher at the University of Coimbra, describes his personal journey to becoming the teacher that he wished he had had. The journey has led him to create a YouTube channel as well as a new course at the university that addresses the questions of why study and how to study. He draws on literature as a means of bringing to life the concepts that he teaches.

* * *

I

In 2019 I became a teacher and a PhD candidate at the same time. Becoming a teacher didn’t make me jump to the other side of the classroom, it only put me on both sides.

I thought of myself as someone familiar with the side of the student. Not because, at that point, I had six years of university education behind me, but because of the challenges I faced during those years as a student.

Law school had been challenging for me. I entered one of the most demanding faculties in Portugal very unprepared. As a high school student who only studied on the evening before his exams, I suddenly found myself faced with thousands of pages of reading material, hours of lectures by people who didn’t captivate me, and studying things that, as it turned out, I didn’t find that interesting. On top of that, there was no certainty that I could afford the next tuition.

These challenges made me pose many questions regarding education. What is the value of education? What does it mean to be a student? How would this education aid myself and others around me? How could I truly educate myself?

Talking with many of my fellow students throughout, I quickly learned that I wasn’t the only one posing those questions. Many students didn’t know why they were studying. They had to make a choice at 18 years old, did it as best they could, and now found themselves asking if they had made the right one.

These questions never left me. Not after I graduated, not after I did my master’s degree, and not when I became a teacher and PhD candidate. On the contrary, now more than ever, I felt the weight of their importance. I was on the receiving end of the questions and felt the need to be able to give answers. If I didn’t, I felt that I didn’t deserve to be a teacher and couldn’t keep being a student.

From early on, I saw being a teacher as an opportunity to do good; to have a positive influence on the lives of young people. Perhaps it was because, as a young student, I wished someone had done that for me. I wanted to be a teacher capable of offering young students a “why” that would drive them to keep chasing their education to its fullest potential.

Whatever the outcome of my journey might be, I had to better myself and take action: become an agent, rather than a subject, of education.

II

I decided that I should be able to teach my students beyond the subjects of my lectures. This meant finding ways in which these subjects related to the world and to individuals themselves. I needed a connection between these realities that was appealing, accessible, and enriching.

Thinking about this, I realized how I had come into contact with a variety of subjects through literature. Stories had made me more interested in philosophy, psychology, history, sociology, and even physics. They did it either by allowing myself to suffer like a character whom chance would never allow me to be or by plunging me into an immersive world that the currents of time would never allow me to swim to.

Why simply write a concept on a blackboard and point at a textbook when you can bring it to life through the words of some of the most eloquent, imaginative, and wise people in the history of the world?

I saw the potential of stories to enrich the way I taught law and the way my students learned. But I also knew it would be difficult to tell students, “Read the subject’s textbook, your notes. . . . Oh! And also, this 400-page novel.” People have smartphones with high-speed Internet and infinite scroll; one must know what he is competing against. Innovation was the answer.

I created a YouTube channel where I read small portions of classical works of literature that touched on topics of law. The videos were small and gave a short explanation of how the specific portion related to a specific concept. Videos were uploaded monthly during the semester and, at the end of each month, students who participated in the project were invited to discuss the ideas of the book and relate them to what was taught in class.

It gave a new depth and life to what we talked about in class. Suddenly, the concept of justice wasn’t just something you read on a textbook but a difficult problem that Aeschylus, the father of tragedy in Ancient Greek theater, posed against the judgment of Athena herself in one of his plays. The death penalty wasn’t just a remote idea, it came to be seen through the eyes of Albert Camus’s character Meursault as he ponders the meaning of truth waiting for the guillotine.

For this project, I was awarded the 2021 Prize for Pedagogical Innovation by the University of Coimbra.

III

I wasn’t completely satisfied after receiving the prize. I had thought carefully about the project and decided it was worthy of pursuit, otherwise I wouldn’t have done it; and it proved to be useful and innovative, otherwise it wouldn’t have been awarded. Still, I came to find its scope limited. I was teaching my students beyond law and pointing them to literature and its ocean of ideas, but there were many more things that I wanted to teach them and couldn’t inside the confines of my lectures on law.

I still saw many of them struggling with their role as university students. I saw lack of motivation born from a sense of uncertainty about the future. I understood that many wanted to learn more and efficiently but didn’t know how to study. For many, as was the case for myself during my graduate years, everything was a question.

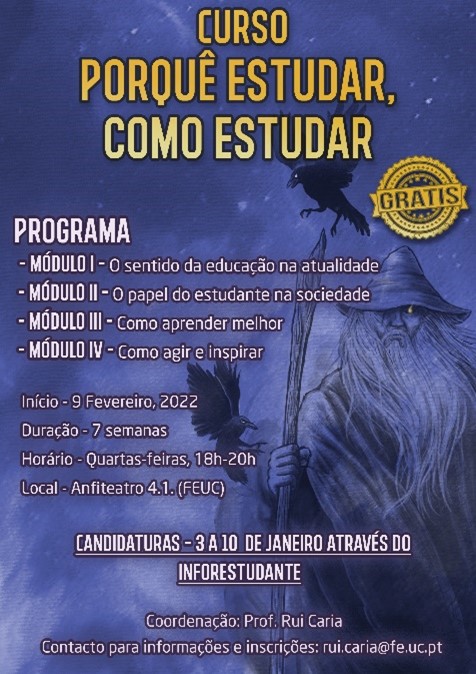

I took it upon myself to provide answers as best as I could. I decided to create a full course, for free, open to all the students at the university, designed to answer two big questions: Why study? How to study? I pitched the idea to the vice dean responsible for the development of undergraduate students and got the approval to create and teach the course.

For months, apart from everything else I was doing, I devoted myself to research and thinking, as honestly and as well as I could, about the answers I would give.

I went after the “why.” My approach to the importance of education had always been grounded in the literature that helped me through tough times. Existentialist philosophy had come to frame much of my world view, especially the work of Albert Camus.[1] The idea of gathering strength within yourself in the face of a world that was indifferent to your existence was dear to me. The intuition in me came to be that, in some way, education should serve to make you stronger. On the other hand, the works of Dostoyevsky had made me believe that there was tremendous value in the good acts one can do for people and that the memory of good could sustain you for a lifetime. Education wasn’t only about making you stronger but about making you stronger so you can be good and help other people.

As I read beyond my literary interests and started to look at how models of development relate to education, I came across the notion of the human capabilities approach in the work of Martha Nussbaum, which resonated with my intuition. Education could in fact be conceptualized as a means of developing capacities in individuals that, in turn, would help them raise other individuals and eventually their own society.

The new challenges posed by the demands of writing a PhD thesis had already put me into contact with the “how” of studying. As I read more about it, it became clearer that studying should be done in a way that was both effective and efficient. The tools necessary to study in this way overlapped with the methods of peak performance that were applicable in several other fields. They lead to the best results. But to perform at your peak, changes in your environment and in yourself were required. Habits must be changed, attention must be sharpened, mindsets must be reinforced. And a vision of the future must be kept vivid and clear: that you can forever learn, forever grow stronger, forever be better, for yourself and for others.

I learned about all of these things and taught them all, for the first time, to the several students that attended the first edition of the “Why Study, How to Study” course at the University of Coimbra.

IV

Creating and teaching a course to students at the university where I studied and now teach was, without a doubt, something I never thought I would be able to do. But it’s one of the most meaningful things I have ever had the honor of doing. Now, I’m glad I had all those doubts as a young man arriving at university. I’m thankful for the suffering that brought them. With time, they transformed from ghosts to guides. I stopped running away from them to start running toward them, and in doing so, I found myself having a journey that I deem worthy of dedicating these words to. One where I had to teach myself to be a teacher, because I wanted to be the one I never had and the one my students deserved. One where I learned how to be a student by never ceasing to ask questions, by not giving up on the hard journey to find the answers. One where I educated others to educate themselves, because I believed there are few greater gifts.

[1] I previously wrote about him in another article for Sylff Voices (https://www.sylff.org/news_voices/28458/).

A video of the author talking about the project can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d54F2XdZC4w&ab_channel=UniversidadedeCoimbra