Voices from the Sylff Community

Máté Fain is a 2022 Sylff Fellow (Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungarian Academy of Sciences Group). For this dissertation, he explored whether environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment strategies are compatible with boosting the corporate “bottom line.” He concludes that good ESG may not always generate superior returns under adverse market conditions such as a pandemic. However, combined with traditional styles, it might yield positive outcomes.

* * *

What do oil, soybean, gold, and water have in common? The answer, at first, may be surprising: in late 2020, water joined these well-known commodities on Wall Street: Californian farmers, hedge funds, and municipalities can now purchase water futures to hedge related risks. Besides water, weather derivatives are another type of commodity responds to environmental challenges but has a more mature market: the Chicago Mercantile Exchange introduced the first exchange-traded weather futures contracts and corresponding options in 1999, mostly tracking cooling or heating days. Some studies have gone even further and explored designing and pricing air-pollution derivatives.

More importantly, these market developments and scientific initiatives on risk management draw attention to sustainability. Sustainability challenges are getting more severe as life-sustaining natural resources become scarce worldwide.

Fostering environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability is an urgent challenge to society. The Paris Agreement signed in 2016 to mitigate climate change or the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established in 2015 with a broader scope on environmental and social concerns underscores the inevitability of addressing sustainability.

Stakeholder theory argues that dealing with stakeholder claims – from customers, employees, local communities, shareholders, and even the natural environment – is imperative for companies to fulfill their mission. Meanwhile, advocates of the trade-off hypothesis contend that resource reallocation to sustainability activities does not pay off; instead, such activities raise operating costs due to the internalization of externalities. Consequently, I examined if, it is possible to reconcile sustainability with companies’ financial objectives.

The Research Question: Does "Doing Well While Doing Good" Prevail?

Alignment with sustainability goals might be assessed from as many angles as stakeholders exist. I focused on shareholder wealth and examined sustainability from an asset-owner perspective: is it possible to boost the bottom line by implementing sustainable corporate practices? Does the “doing well while doing good” concept prevail? If so, investors, as influential stakeholders, may drive sustainable economic growth.

Studying the impact of sustainability on shareholder value-added may manifest in several forms. Firstly, the analysis might cover accounting profitability, respond to how equity markets price sustainability, and identify the potential risk-adjusted excess returns for investors. My research intended to explore the last case.

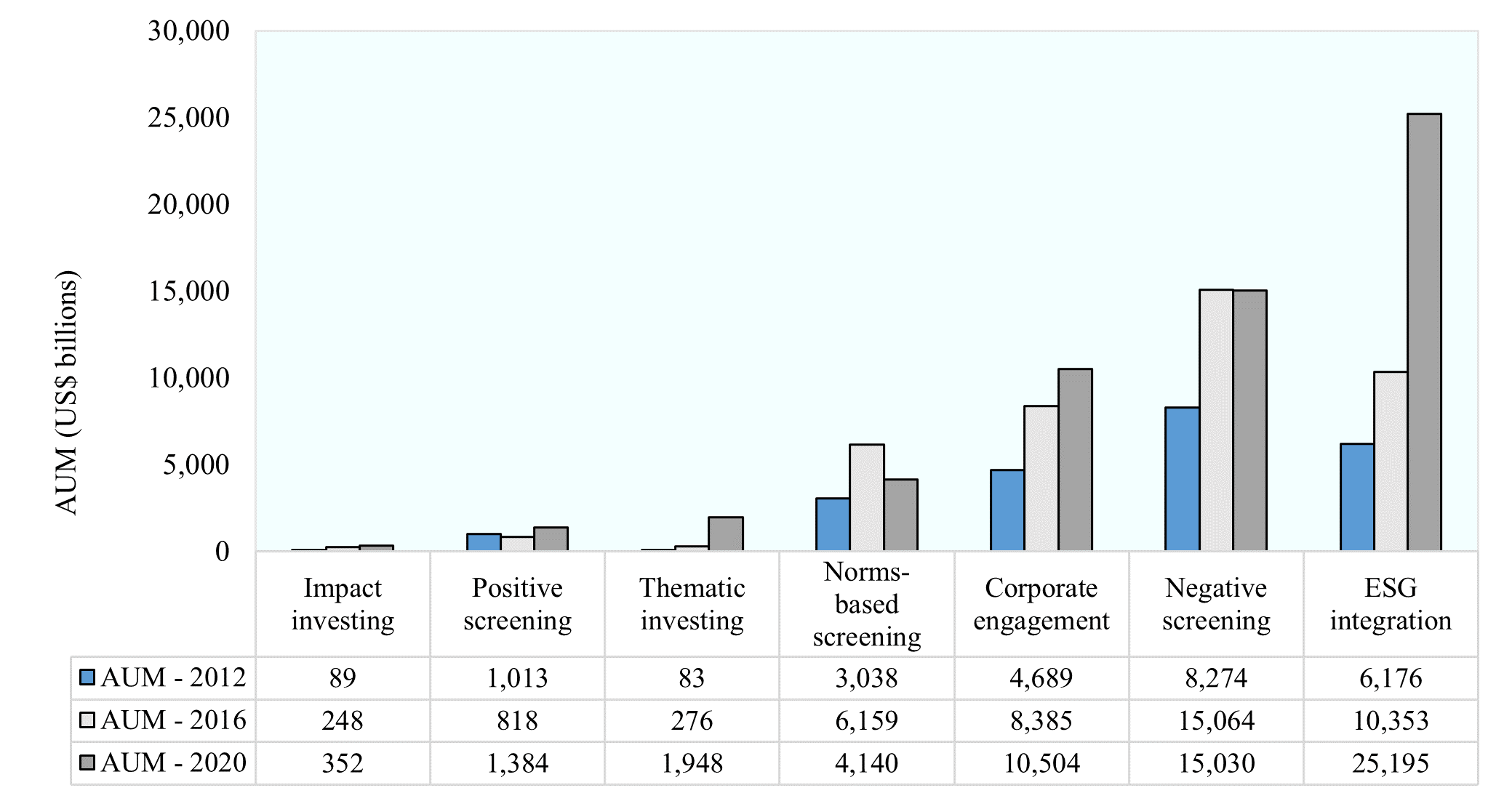

In the investment literature, environmental, social and governance (ESG) is a broad umbrella term for firms’ sustainability . A wide range of ESG-conscious investment strategies exists, from exclusionary screening to direct shareholder engagement. My research concentrated on the ESG integration approach (applying ESG scores ranging from 0 to 100 of corporations to compile stock portfolios) and ESG-themed investing (equity portfolios that use megatrends such as energy efficiency, aging population, water scarcity, and cybersecurity). ESG integration is exceptionally popular, with US$25,000 billion in total assets under management, while thematic investing is the most significantly rising strategy, with a 2,250 per cent increase in 8 years.

Figure 1. Global growth of sustainable investing strategies

Note: AUM stands for “assets under management.” Source: GSIA (2020, p. 11)

Note: AUM stands for “assets under management.” Source: GSIA (2020, p. 11)

For the ESG integration strategy, I applied separate environmental, social and governance ratings, and every stock belonged to one of the following portfolios: leaders, followers, loungers, laggards, and not rated. Thematic portfolios covered nine UN SDG-related challenges, such as water scarcity, aging population, and cybersecurity concerns. Each thematic portfolio fitted environmental, social and governance megatrends and encompassed firms with business models addressing critical sustainability challenges.

In compiling the ESG portfolio, more than 100 different investment styles, industries, and country exposures were controlled for to filter out secondary factor effects. Altogether the database included more than 15 million data points. The methodology followed a factor portfolio construction procedure: stock weights and returns were derived from extended Fama-MacBeth cross-sectional regressions (Fama, 1976; Fama and MacBeth, 1973). The time-series analysis of ESG factor portfolio returns applied the Fama and French (2018) right-hand-side approach.

Contribution

This research contributes to the existing investment literature on sustainability in several ways. Firstly, it complements the active debate about the role of ESG in general, which is far from settled (i.e., it is still an open question if it is possible to achieve significant extra returns with ESG, or, on the contrary, these investments are underperformers causing loss to investors). Secondly, to the best of my knowledge, no one has yet applied a stakeholder-based conceptual model that differentiates “organizational” and “global” sustainability. Originally Garvare and Johansson (2010) drew the distinction between organizational and global sustainability. ESG integration is consistent with organizational sustainability, while ESG-themed investing corresponds more to global sustainability.

The dissertation emphasizes the megatrend concept and integrates signaling theory into the stock selection processes. It also introduces a new mathematical formula for measuring megatrend exposures. Using the right-hand-side approach in the ESG framework is a novelty as well. Further, ESG-themed investing is a relatively new strategy, having shorter history than other strategies, such as negative screening, which was the pioneer sustainability investing strategy; hence, it is under-researched in the literature. Finally, the database used is unique and comprehensive, making the data suitable for measuring the pure performance of ESG factors.

Empirical Results in a Nutshell

The analyses revealed some remarkable findings. Investors allocating resources to ESG leaders and thematic portfolios achieved returns in the longer term commensurate with risk. Further, in the ESG integration strategy, a nonlinear relation prevailed, which contradicts the literature’s most common findings that there is either a positive, negative or neutral relationship between financial and ESG performance (non-linearity means that financial performance does not increase proportionally with ESG performance, as there is a “peak” after which increasing ESG performance does not come with significantly higher financial performance; sometimes financial performance even decreases, suggesting an inverted-U graphical representation of the ESG-financial performance relation), supporting diminishing marginal returns to ESG (law of diminishing returns: a firm will get less and less extra output – here, financial returns – when it adds additional units of an input – here, better ESG compliance). Next, during the exogenous shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, the figures did not corroborate the literature’s “flight to quality” concept (i.e., investors begin to shift their assets away from riskier investments into safer ones). Finally, no sufficient evidence was found for ESG factors to complement Fama and French models (Fama-French models detect factors such as firm size and investment policy that could explain stock returns; if a new factor is found, it could be added to the previous ones).

In summary, in most cases, investors could realize at least fair returns with sustainable investing. This finding is consistent with the efficient-market hypothesis, i.e., share prices reflect all public information, stocks trade at their fair market value. In other words, although there is only a slight chance for investors to gain superior risk-adjusted returns, they could contribute to the higher goals of sustainability without sacrificing returns.

Implications

The empirical results imply that most ESG portfolios yielded non-negative excess returns, even after accounting for transaction costs up to 25-50 basis points per annum. Higher transaction costs, as is the case for some exchange traded funds (frequently abbreviated ETFs) with expense ratios reaching 80-100 basis points per annum, may indicate two things: ESG-themed megatrend investors are willing to sacrifice approximately 25-50 basis points of annual return to remain aligned with sustainability targets, or the expense ratio may well decline in the future (nowadays, the average expense ratio is around 0.60 per cent).

Portfolio managers who integrate sustainability in their investment portfolios undertake a dual optimization process that combines ESG strategies with fundamental valuation. The proposed ESG pure factor portfolios might be utilized as smart beta indices to measure investment portfolios’ ESG factor exposure. This method is superior to calculating the overall ESG rating of investment portfolios currently commonly used by asset managers, as it separates the performance contribution of ESG from the secondary factors such as geographical, industry, or style effects.

ESG portfolios allow asset owners and managers to align their investment policies with the requirements and targets of international standards and regulations. According to a representative of the central bank of Hungary, whom I interviewed, both strategies are consistent with the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation requirements. Thematic investing might be aligned with the Taxonomy Regulation and can be flexibly adapted to the SDGs and the climate goals of the Paris Agreement.

These results do not provide sufficient evidence for “flight to quality” during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic regarding ESG leaders, which contradicts Albuquerque et al. (2020), Broadstock et al. (2021), and Ding et al. (2021). One possible explanation might be that secondary factor effects substantially influence good ESG portfolios. Once these secondary effects are considered and filtered out, the otherwise observable outperformance disappears.

In summary, good ESG is not necessarily a panacea to generate superior returns during adverse market conditions such as a pandemic. However, combined with traditional styles or sectors, it might yield positive outcomes.

References

Albuquerque, R., Koskinen, Y., Yang, S., & Zhang, C. (2020). Resiliency of environmental and social stocks: An analysis of the exogenous COVID-19 market crash. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 9(3), 593-621. https://doi.org/10.1093/rcfs/cfaa011

Broadstock, David C., Kalok Chan, Louis T. W. Cheng, and Xiaowei Wang. “The Role of ESG Performance During Times of Financial Crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China.” Finance Research Letters 38 (2021): 101716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2020.101716.

Ding, Wenzhi, Ross Levine, Chen Lin, and Wensi Xie. “Corporate Immunity to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Financial Economics 141, no. 2 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.03.005.

Dodd, E. Merrick, Jr. “For Whom Are Corporate Managers Trustees?” Harvard Law Review 45, no. 7 (1932): 1145–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/1331697.

Fama, Eugene F. Foundations of Finance: Portfolio Decisions and Securities Prices. New York: Basic Books, 1976.

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. “Choosing Factors.” Journal of Financial Economics 128 (2018): 234–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.02.012.

Fama, Eugene F., and James D. MacBeth. “Risk, Return, and Equilibrium: Empirical Tests.” Journal of Political Economy 81 (1973): 607–36. https://doi.org/10.1086/260061.

Garvare, Rickard, and Peter Johansson. “Management for Sustainability – A Stakeholder Theory.” Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 21 (2010): 737–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2010.483095.

Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. GSIA, 2020. http://www.gsi-alliance.org/trends-report-2020/.