Voices from the Sylff Community

Hungary found itself isolated in the EU when it initially blocked the implementation of the OECD agreement on a minimum corporate tax rate for multinationals. In an article adapted from a paper that was submitted to Pázmány Péter Catholic University Budapest, Tamás Zoltán Wágner (Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2022) writes that rather than stonewalling the agreement, the government wisely shifted its strategy, enabling it to embrace the deal while maintaining its tax sovereignty and competitiveness.

* * *

Following the October 2021 agreement on a global minimum tax within the OECD framework on base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS), the focus in the European Union shifted to the question of how this should be implemented in national and EU legal systems. This became an issue because member states with low corporate tax rates, such as Ireland and Hungary, feared losing their competitiveness and were critical of the implementation efforts, triggering heated debate.

Hungary initially strongly opposed the implementation of the tax in the EU and anticipated vetoing it if necessary. Later, though, the Hungarian government adjusted its position and focused its efforts on how it could avoid implementing an actual tax increase. In the following, after briefly presenting the rules on the global minimum tax, I will examine whether Hungary’s fear was justified and then analyze the reasons for the change in the Hungarian position, which evolved from initial rejection to a search for a compromise.

Discouraging Tax Planning

Regarding the OECD agreement, it is important to point out that it is a two-pillar solution. The first pillar addresses the largest and most profitable multinational enterprises (MNEs) with a global turnover of more than €20 billion (€10 billion from 2028) and a pretax profitability ratio exceeding 10%. In countries where they sell their products and services and where they have consumers, these companies will need to pay 25% of their profits. By implementing this tax, countries that introduced or planned to introduce a digital tax will abandon it and commit to not introducing it in the future.

The second pillar is the global minimum tax, which aims to ensure that multinationals pay a minimum of 15% on all their profits in each jurisdiction where they have subsidiaries or establishments. According to pillar two rules, it is necessary to examine on a country-by-country basis whether the taxation of a given multinational reaches the effective tax rate. The global minimum tax applies to MNEs with an annual consolidated group revenue of €750 million operating in at least two of the four years preceding the current year and in two jurisdictions. States have the option of including for minimum taxation groups of companies operating in their own territories even if they do not have foreign subsidiaries or establishments. Not subject to the minimum tax, though, are government departments, international organizations, nonprofit organizations, pension or investment funds that are the ultimate parent companies of a group of companies, and the assets held by such entities.

The rate of the global minimum tax is not a nominal but an effective tax rate: only the taxes actually paid matter. Thus, if the effective tax rate of one of the subsidiaries in a given jurisdiction is less than 15%, then an additional tax is levied, to be paid by the parent company or the subsidiary. According to the three-element scheme developed by the OECD, the income inclusion rule (IIR) provides for the imposition of a top-up tax to make up for any difference in the taxes paid, or, if there is no IIR in the relevant jurisdiction, the undertaxed payments rule (UTPR) operates as a backstop to ensure that the tax rate for an MNE group is achieved by prohibiting cost deductions for group members or through similar mechanisms. The third element of the regulation is the subject to tax rule (STTR), a treaty-based rule that allows certain states to tax intra-group payments when the tax rate for such payments is below the minimum rate. This had been prohibited under the double taxation convention.

In the light of the above, it is clear that, contrary to the OECD BEPS Action Plan, adopted in 2013, the global minimum tax does not place emphasis on protecting the tax base but on eliminating the cause of tax planning: its basic philosophy assumes that MNEs will not use tax avoidance techniques if the tax advantage is taken away. It also aims to prevent a “race to the bottom” based on continuous decline in corporate tax rates and to reduce divergences between national tax systems, which also facilitate tax avoidance techniques.

Backlash from Hungarian Officials

Low-tax countries like Ireland and Hungary initially sharply criticized the concept because they feared losing their competitiveness and becoming less attractive to foreign investors. They also complained that the introduction of a global minimum tax would limit their tax policy, since it would essentially force them to raise their corporate tax rates: even if they apply lower tax rates, other states will collect the difference anyway. This fear seemed justified because, as Hindriks and Nishimura showed, the introduction of a global minimum tax would reduce the gap between high-tax and low-tax countries, which would also affect the ability to attract capital: large companies would be less likely to move their profits to low-tax countries.

Overall, countries with low tax rates can expect a decrease in tax revenues, while countries with high tax rates can expect an increase in tax revenues. In the longer term, the loss of a tax advantage could also jeopardize the very existence of tax havens and other preferential tax regimes. For this reason, these countries need to pursue one of the following strategies:

- Maintain the status quo (for states that do not levy a corporate tax)

- Raise the corporate tax rate to the level of the global minimum tax

- Introduce a corporate tax system that applies to all companies

- Introduce a threshold-based corporate tax system, which means that only companies subject to a global minimum tax must pay the higher corporate tax rate

Another strategy is for the state, in order to avoid an effective tax increase, to include as many types of tax as possible in the effective tax burden. This, in my view, is the best way forward, and it was, in fact, the choice made by Hungary.

Hungary, like other low-tax countries, was initially very skeptical about the global minimum tax. The proposed legislation triggered the following preliminary remarks from governmental officials:

- “We should avoid a war of competition among tax systems in the global fight against harmful tax competition.”

- “It is essential to respect the fiscal sovereignty of states regarding the taxation of income generated locally, and profits attributable to real economic activity shall be exempted to the greatest possible extent.”

- “The situation should be avoided where the regulation penalizes differences between different methods of calculating the tax base instead of low taxation, which could substantially restrict the free movement of capital even between states applying tax rates close to the average.”

- “A set of rules applicable only to subsidiaries would create a significant competitive disadvantage for capital-importing countries and, in many cases, lead to the relocation of headquarters to low-tax states.

These remarks were later supplemented by criticisms, such as:

- “This reduces the sovereignty of the Hungarian tax system and would result in a competitive disadvantage for the European Union, which is unacceptable in the particularly sensitive economic situation caused by the Russo-Ukrainian war.”

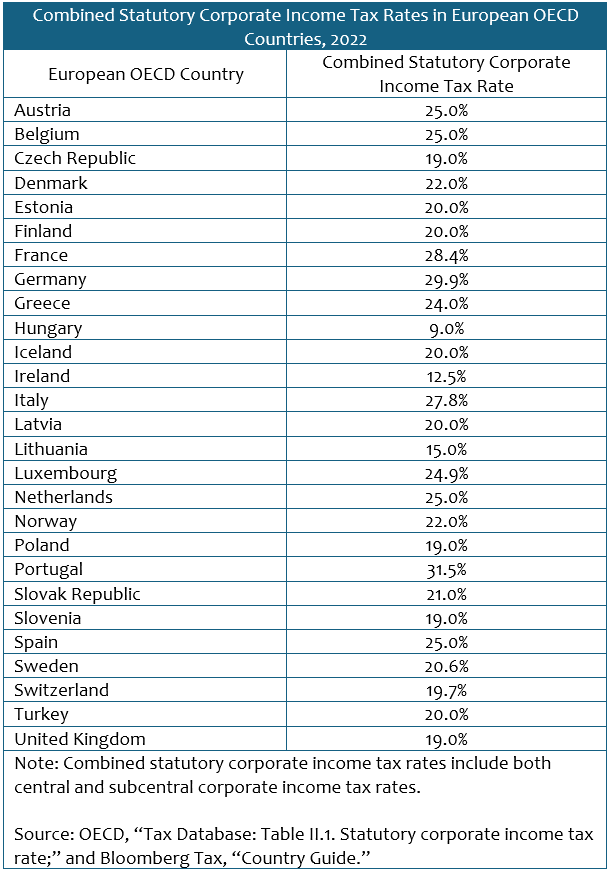

- “The Hungarian corporate tax rate (9%) is much lower than that of all our trading partners, which is the cornerstone of the Hungarian economic policy.”

- “It would endanger hundreds of thousands of jobs in our country and would mean a return to the situation of 2010 in terms of corporate tax.

A Threat to Competitiveness

These comments indicate that the Hungarian government viewed the issue of the global minimum tax from a sovereigntist, tax competitiveness perspective. This was understandable, given the logic of Hungary’s economic policy: the implementation of an actual tax increase would endanger the competitiveness it had enjoyed thanks to low corporate tax rates. At the same time, the Hungarian government was under great pressure to support the adoption of the EU directive. After all, even if it did not introduce a global minimum tax, the tax difference would simply be collected by other governments. In other words, companies operating in Hungary will have to reckon with an increase in the tax burden no matter how Budapest decided, and moreover, by not implementing the tax, the government would be voluntarily forgoing sources of revenue that it could otherwise have claimed.

The situation of the Hungarian government became more difficult by the fact that on September 9, 2022, the EU’s largest economies—France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands—announced that if the EU directive was not adopted, they were ready to introduce the global minimum tax unilaterally. This step would have meant tens of billions of forints in additional tax liability just for German companies operating in Hungary, whose average effective corporate tax rate, due to various tax breaks, barely reached 3%. Hungary also faced concrete pressure owing to the termination of the US-Hungary double taxation avoidance treaty in early July 2022 and the decision of the European Parliament on national vetoes undermining the global tax agreement, also in early July.

Regarding the former, it is worth pointing out that this was not unexpected: even before the Ecofin (Economic and Financial Affairs Council) meeting in June 2022, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned Hungary to change its position on the global minimum tax or face the termination of the bilateral double taxation treaty. Although the treaty did not expire until January 2024, the United States showed no intention of concluding a new treaty with Hungary. In Tibor Pálszabó’s opinion, the potential implications for private individuals include the following:

- If they become residents in both countries, their world income would become taxable in both states.

- Even without multiple residence, they may become liable for taxation in the country of income in situations where they had previously been exempt, that is, a double taxation situation may arise.

- The conventional exemptions that would have resolved such double taxation issues will be abolished.

In the case of businesses, there will be a negative change mainly in relation to the withholding tax: dividends, interest, and royalties will be subject to a withholding tax of 30% instead of the previous 5%. The Hungarian economy will experience the negative effects even in the short term (such as through a direct tax revenue loss of 70 billion to 80 billion forints due to the reorganization of the investment structure of US companies), but in the long term the situation is more serious: there could be a significant decline in the economy’s ability to attract capital and retain its labor force.

The European Parliament, meanwhile, criticized the unanimity requirement for decision-making in the field of taxation, calling on the European Commission and the Council to find alternative ways for the EU to fulfil its OECD/G20 commitments, such as through “enhanced cooperation,” unilateral implementation by member states, and transition to qualified majority voting. It also demanded that Hungary lift its veto and urged the Commission and member states to block approval of Hungary’s recovery and resilience plan unless all the criteria were fully complied with.

A Shift in Strategy

Based on the above, it was apparent that by the end of 2022 the Hungarian government found itself in a very difficult situation: it was isolated in the EU and risked being lumped together with conventional tax havens. The Hungarian position, which seemed rigid at first, thus gradually shifted to another strategy: including as many domestic taxes (such as the local business tax) as possible in the effective tax burden in order to avoid actually raising the corporate tax. In this respect, negotiations were successful, as Hungary achieved the following goals:

- The inclusion of the local business tax in the global minimum tax

- Exemption of real economic activity

- Simultaneous introduction of rules in all countries adopting the global minimum tax (so that Hungary does not suffer a competitive disadvantage)

- The likely collection of the tax difference from target MNE groups in the form of differentiated domestic taxes so that there is no need to change the corporate tax rate of 9%.

Subsequently, on December 12, 2022—after Hungary lifted its veto—EU member states reached an agreement on the directive submitted by the European Commission at the end of 2021 to ensure a global minimum level of taxation for MNEs, which entered into force on December 14, 2022.

The example of Hungary highlights that, contrary to initial fears, the introduction of the global minimum tax does not necessarily entail an increase in the corporate tax burden or restrict the tax sovereignty of low-tax countries if other types of domestic taxes (like the local business tax) are included in the effective tax burden. Therefore, the right strategy for the global minimum tax is not rigid resistance, as it can easily lead to international isolation and reputational loss (such as by being branded a tax haven), but to negotiate a compromise so that competitiveness can be maintained even after implementing the global minimum tax.

References

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. “Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy.” https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-on-a-two-pillar-solution-to-address-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-october-2021.pdf.

Czoboly, Gergely. “Globális minimumadó bevezetésének lehetséges hatásai a klasszikus adóstruktúrákra” [Possible Effects of the Introduction of a Global Minimum Tax on Classical Tax Structures]. Miskolci Jogi Szemle, 2021/5. (3. különszám).

Nobilis, Benedek. “Globális minimumadó: ez nem csak Magyarországnak fájhat” [Global Minimum Tax: This May Hurt Not Just Hungary]. Portfolio. https://www.portfolio.hu/gazdasag/20210413/globalis-minimumado-ez-nem-csak-magyarorszagnak-fajhat-477960.

Hindriks, Jean and Yukihiro Nishimura. “The Compliance Dilemma of the Global Minimum Tax.” LIDAM Discussion Paper CORE, 2022/13. https://dial.uclouvain.be/pr/boreal/object/boreal%3A259159/datastream/PDF_01/view.

Essid, Colleen. “The Global Minimum Tax Agreement: An End to Corporate Tax Havens?” SLU Law Journal Online, 73. https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lawjournalonline/73.

Deloitte Insights. “Global Minimum Corporate Income Tax. How Might Countries with ‘Low’ or ‘No’ Taxation Respond?” https://www2.deloitte.com/xe/en/pages/tax/articles/global-minimum-corporate-income-tax.html.

Prinz, Dániel and Eszter Kabos. “Miért van szükség globális társasági minimumadóra?” [Why Do We Need a Global Minimum Tax?]. Qubit. https://qubit.hu/2021/08/02/miert-van-szukseg-globalis-tarsasagi-minimumadora.

Hungarian National Assembly. “Az Országgyűlés 24/2022. (VI. 21.) OGY határozata a globális minimumadó bevezetésére vonatkozó európai uniós irányelv elfogadásának elutasításáról” [24/2022 (VI. 21) Decision of the Hungarian National Assembly Rejecting the Adoption of an EU Directive Introducing a Global Minimum Tax].

Kiss, Rajmund. “Kerékbe tört versenyképesség? A globális minimumadó súlyos kockázatairól” [Competitiveness in Tatters? The Serious Risks of the Global Minimum Tax]. Mathias Corvinus Collegium. https://corvinak.hu/gazdasag/2021/05/19/kerekbe-tort-versenykepesseg-a-globalis-minimumado.

Government of Hungary. “A globális minimumadó jelentené a kegyelemdöfést az európai gazdaságnak” [A Global Minimum Tax Would be a Coup de Grâce for the European Economy]. https://kormany.hu/hirek/a-globalis-minimumado-jelentene-a-kegyelemdofest-az-europai-gazdasagnak.

Pardavi, László. “Néhány gondolat a globális minimumadó történetéről, bevezetésének okairól és lehetséges magyarországi hatásairól” [A Few Thoughts on the History of the Global Minimum Tax, the Reasons for Its Introduction, and Its Possible Impact on Hungary]. In Barna Arnold Keserű, Katalin Szoboszlai-Kiss, and Richárd Németh, eds., Salus Vocalis. Csegöldi indulás - Győri érkezés. Ünnepi tanulmányok Fazekas Judit tiszteletére. Győr, Universitas-Győr Nonprofit Kft, 2023.

Adó Online. “Niveus: Magyarország a globális minimumadóról szóló csatát hamarosan elveszítheti [Niveus: The Battle over the Global Minimum Tax Could Soon Be Lost for Hungary]. https://ado.hu/ado/niveus-magyarorszag-a-globalis-minimumadorol-szolo-csatat-hamarosan-elveszitheti/.

Government of Hungary. “Az Egyesült Államok nyomást akar gyakorolni Magyarországra” [The United States Wants to Put Pressure on Hungary]. https://kormany.hu/hirek/az-egyesult-allamok-nyomast-akar-gyakorolni-magyarorszagra.

Pálszabó, Tibor, Veronika Oláh, and Dániel Bajusz. “USA-magyar adóegyezmény felmondása: mi lesz veletek expatok?” [Termination of the US-Hungarian Tax Treaty: What Will Happen to Expats?]. EY. https://www.ey.com/hu_hu/tax/usa--magyar-adoegyezmeny-felmondasa--mi-lesz-veletek-expatok-.

Dajkó, Ferenc Dániel. “Sérülnek az amerikai-magyar kapcsolatok? – Szakértők a kettős adóztatás felmondásáról” [Are US-Hungarian Relations Damaged? Experts on the Termination of Double Taxation]. novekedes.hu. https://novekedes.hu/interju/serulnek-az-amerikai-magyar-gazdasagi-kapcsolatok-szakertoket-kerdeztunk-mi-varhato-a-kettos-adoztatas-egyezmeny-felmondasa-utan.

European Parliament. “European Parliament Resolution of 6 July 2022 on National Vetoes to Undermine the Global Tax Deal (2022/2734(RSP)).” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0290_EN.html.

Mattiassich, Enikő and Károly Szóka. “Impact of the Introduction of A Global Minimum Tax.” In Mustafa Göktuğ Kaya and Haldun Soydal, eds., International Congress of Finance and Tax. March 10–11, 2023, Konya, Türkiye.

Council of the European Union. “Council Directive (EU) 2022/2523 of 14 December 2022 on Ensuring a Global Minimum Level of Taxation for Multinational Enterprise Groups and Large-Scale Domestic Groups in the Union.” Official Journal of the European Union, L 328, 22.12.2022, pp. 1–58. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2523/oj.