Voices from the Sylff Community

Apr 12, 2024

Genetic-Level Explorations into the Gut Microbiota

To analyze the relationship between the gut microbiota and host diseases, Tomoya Tsukimi (Keio University, 2021) used an SRG award to conduct experiments at the University of Tsukuba, where he examined the mechanisms of intestinal bacterial colonization at the genetic level. He eventually hopes to enhance treatment outcomes through the development of personalized medicine.

* * *

About 40 trillion bacteria inhabit the human body, the majority of them in the gastrointestinal tract.(1) One place where these bacteria are particularly abundant is our large intestine. These bacteria, collectively known as the gut microbiota, have a lot of genes—even more so than human beings.(2, 3)

The intestinal bacteria form part of a complex ecosystem in the gut as they interact with host cells. Studies have shown that they boost resistance to pathogen infection,(4) affect host bile acid metabolism,(5) help maintain immune homeostasis,(6) and are even involved in brain functions. (7) Furthermore, there is growing evidence of a relationship between the gut microbiota and host diseases—not only digestive disease(8, 9) but also a wide range of systemic ailments like cancer,(10) diabetes,(11) and psychiatric disorders.(12)

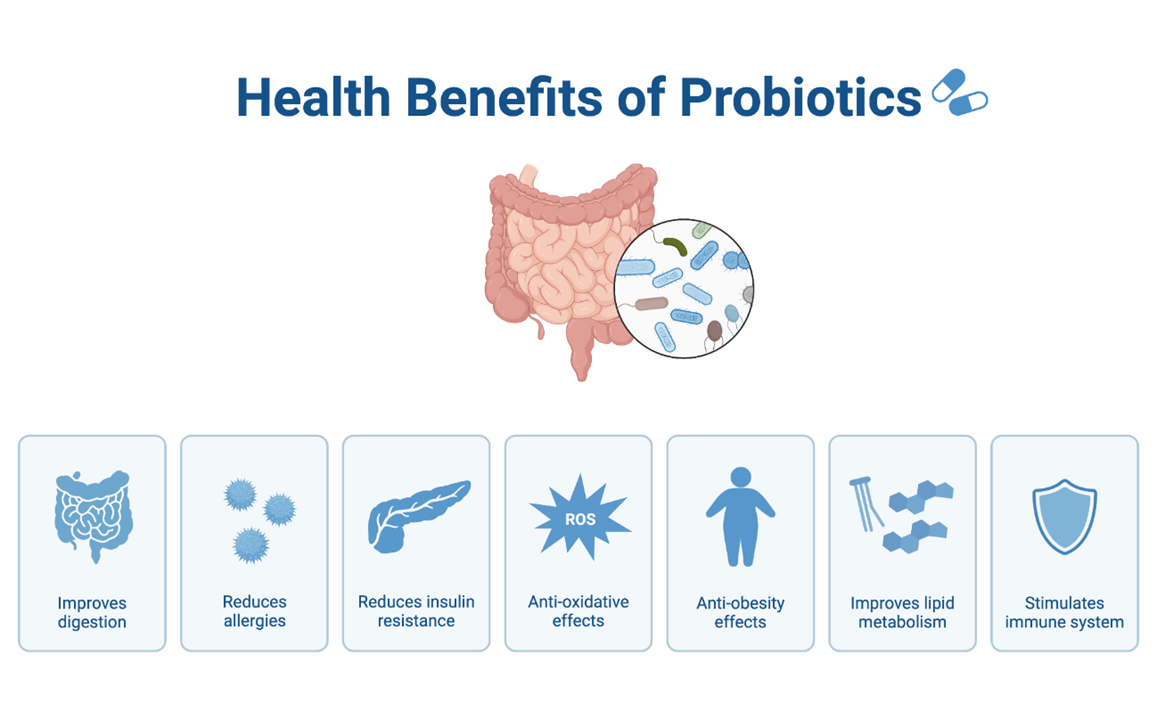

The gut microbiota also influences the pharmacological effects of disease treatments.(13) This has spurred the development of methods to control the gut microbiota for the prevention and treatment of disease,(14, 15) such as through prebiotics, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation.

Health Benefits of Probiotics, from BioRender, https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates/figures/all/t-64400e6d675cf5f619cd17db-health-benefits-of-probiotics.

The question my research seeks to answer is, “What factors are important for the bacterial colonization of the host intestinal tract?” Recent studies have shown that imbalances in the intestinal microbiota are associated with various diseases. While fecal microbiota transplantation therapy and probiotics have been used to treat these diseases, studies indicate that exogenous bacteria have difficulty colonizing a patient’s intestines.(16)

Previous studies have discussed intestinal bacteria based on information regarding genus-level composition. But dietary composition exerts selective pressure on not only the species but also variants and substrains within the same species.(17) This points to the importance of studying the mechanism of intestinal bacterial colonization at the genetic level. I have therefore focused on genetic mutations of E. (Escherichia) coli during intestinal colonization in mice. E. coli is prevalent in the human gut as well, and its genetic manipulation is well established.

Identifying Genes Important for E. Coli Colonization

E. coli has approximately 4,000 genes. I examined which genes mutated when E. coli colonizes the mouse intestine and the mechanism by which these genes mutated. I decided to use germ-free (GF) mice, which has no bacteria in their intestines, thus enabling me to clarify the relationship between the host mouse and E. coli mutations.

Unfortunately, the laboratory with which I am affiliated does not have a facility to breed GF mice. So, I conducted my experiments at the University of Tsukuba, a national research university in Ibaraki Prefecture, which has one of the best-equipped animal experiment facilities in Japan. It was thanks to a Sylff Research Grant that I was able to finance my travel and lodging expenses to carry out my research there, so I would like to thank the Sylff Association for giving me this opportunity to advance my studies.

The University of Tsukuba campus.

I have been able to identify the genes that appear to be important for the colonization of E. coli. The study also helped to elucidate the adaptive mechanisms of the gut microbiota. A paper summarizing the results is currently under review for publication in a peer-reviewed, international journal.

Developing a Treatment for Bowel Diseases

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are inflammatory bowel diseases that are associated with intestinal bacteria for which effective treatments have not yet been established. There are some 300,000 patients of the two diseases in Japan and 1.6 million in the United States. This study has the potential to more clearly explain the bacterial colonization mechanism, leading to a highly accurate method for controlling the intestinal environment and contributing to the development of a treatment for these diseases.

Although there have been cases of clinical recovery using prebiotics, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation therapy, the success rate varies widely from one individual to another. By focusing on the mechanism of intestinal colonization at the genomic level, the findings of this study can be used to develop methods for controlling the intestinal environment that are specific to the individual. In the future, I hope to contribute to the development of tailor-made medicine targeting intestinal bacteria and to the realization of a society where everyone can lead a healthy life.

I believe this research also has implications for discussions of human traits that are universal and those that are unique. As mentioned above, about 40 trillion bacteria inhabit the human body. This is comparable to the number of human cells. Since bacteria are associated with various diseases, “the human body can be considered a superorganism; a communal group of human and microbial cells all working for the benefit of the collective.”(18)

Studies have shown that bacterial composition and metabolite concentrations in the gut differ among individuals.(19, 20) This suggests that commensal bacteria—those that live in harmony with humans—can be regarded as one factor that distinguishes the self from others. Studies like mine on commensal bacteria may therefore offer clues to such overarching questions as “What am I?” and “What makes me different from others?”

References

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. 2016. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS biology 14:e1002533.

- Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, Mende DR, Li J, Xu J, Li S, Li D, Cao J, Wang B, Liang H, Zheng H, Xie Y, Tap J, Lepage P, Bertalan M, Batto JM, Hansen T, Le Paslier D, Linneberg A, Nielsen HB, Pelletier E, Renault P, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Turner K, Zhu H, Yu C, Li S, Jian M, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zhang X, Li S, Qin N, Yang H, Wang J, Brunak S, Dore J, Guarner F, Kristiansen K, Pedersen O, Parkhill J, Weissenbach J, et al. 2010. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464:59-65.

- Nishijima S, Suda W, Oshima K, Kim SW, Hirose Y, Morita H, Hattori M. 2016. The gut microbiome of healthy Japanese and its microbial and functional uniqueness. DNA research 23:125-33.

- Ubeda C, Djukovic A, Isaac S. 2017. Roles of the intestinal microbiota in pathogen protection. Clinical & translational immunology 6:e128.

- Sayin SI, Wahlstrom A, Felin J, Jantti S, Marschall HU, Bamberg K, Angelin B, Hyotylainen T, Oresic M, Backhed F. 2013. Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. Cell metabolism 17:225-35.

- Kawamoto S, Maruya M, Kato LM, Suda W, Atarashi K, Doi Y, Tsutsui Y, Qin H, Honda K, Okada T, Hattori M, Fagarasan S. 2014. Foxp3(+) T cells regulate immunoglobulin a selection and facilitate diversification of bacterial species responsible for immune homeostasis. Immunity 41:152-65.

- Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, Cryan JF. 2011. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108:16050-5.

- Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. 2007. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104:13780-5.

- Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, Vazquez-Baeza Y, Van Treuren W, Ren B, Schwager E, Knights D, Song SJ, Yassour M, Morgan XC, Kostic AD, Luo C, Gonzalez A, McDonald D, Haberman Y, Walters T, Baker S, Rosh J, Stephens M, Heyman M, Markowitz J, Baldassano R, Griffiths A, Sylvester F, Mack D, Kim S, Crandall W, Hyams J, Huttenhower C, Knight R, Xavier RJ. 2014. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn's disease. Cell host & microbe 15:382-392.

- Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Clancy TE, Chung DC, Lochhead P, Hold GL, El-Omar EM, Brenner D, Fuchs CS, Meyerson M, Garrett WS. 2013. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell host & microbe 14:207-15.

- Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, Guiot Y, Derrien M, Muccioli GG, Delzenne NM, de Vos WM, Cani PD. 2013. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110:9066-71.

- Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, Mao H, Ma Z, Yin Y, Wang W, Tang W, Tan Z, Shi J, Li L, Ruan B. 2015. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain, behavior, and immunity 48:186-94.

- Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, Zeller G, Telzerow A, Anderson EE, Brochado AR, Fernandez KC, Dose H, Mori H, Patil KR, Bork P, Typas A. 2018. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 555:623-628.

- Markowiak P, Slizewska K. 2017. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients 9:1021.

- Crook N, Ferreiro A, Gasparrini AJ, Pesesky MW, Gibson MK, Wang B, Sun X, Condiotte Z, Dobrowolski S, Peterson D, Dantas G. 2019. Adaptive strategies of the candidate probiotic E. coli Nissle in the mammalian gut. Cell host & microbe 25:499-512.

- van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, Fuentes S, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, Visser CE, Kuijper EJ, Bartelsman JF, Tijssen JG, Speelman P, Dijkgraaf MG, Keller JJ. 2013. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 368:407-15.

- Yilmaz B, Mooser C, Keller I, Li H, Zimmermann J, Bosshard L, Fuhrer T, Gomez de Aguero M, Trigo NF, Tschanz-Lischer H, Limenitakis JP, Hardt WD, McCoy KD, Stecher B, Excoffier L, Sauer U, Ganal-Vonarburg SC, Macpherson AJ. 2021. Long-term evolution and short-term adaptation of microbiota strains and sub-strains in mice. Cell host & microbe 29:650-663.

- Sleator RD. 2010. The human superorganism - of microbes and men. Medical hypotheses 74:214-5.

- Song EJ, Shin JH. 2022. Personalized Diets based on the Gut Microbiome as a Target for Health Maintenance: from Current Evidence to Future Possibilities. J Microbiol Biotechnol 32:1497-1505.

- Di Domenico M, Ballini A, Boccellino M, Scacco S, Lovero R, Charitos IA, Santacroce L. 2022. The Intestinal Microbiota May Be a Potential Theranostic Tool for Personalized Medicine. J Pers Med 12.