Voices from the Sylff Community

Feb 25, 2025

Populism’s Mitigated Potency in Japan and Implications for Mature Democracies

Despite Japan’s economic struggles, populism has made limited electoral impact. Jiajia Zhou (Columbia University, 2017) explores how the local organizational strength of incumbent parties mitigates the effectiveness of populist rhetoric and, in doing so, may facilitate the pursuit of electorally challenging policies.

* * *

Populism is an endogenous offshoot of representative democracy. It is a rhetoric that appeals to shared grievances among the electorate, blames representative elites, and in this process “[takes] advantage of democracy’s endogenous discontent with the domineering attitude of the few over the many” (Urbinati 2019, 119).

What is surprising about populism today is not its presence but its potency—that the basic claims of extreme majoritarianism capture the hearts of enough voters to make waves in electoral outcomes. Some scholars have opted to view populism as a strategy employed by political actors to mobilize “large numbers of mostly unorganized followers” (Weyland 2001, 14). This aligns with the origin of populism as a concept coined to differentiate electoral politics dominated by charismatic leaders in Latin America from class-based mobilization in European democracies (Roberts 2015, 144).

However, this definition magnifies the present condition while overlooking a key question, that is, why has the anti-elite claim come to amass so much electoral influence in democracies where elections used to be anchored in various loci of organized support? Part of the answer lies in the weakening geographical strength of political parties in mature democracies.

Resisting Populism at the Local Level

Japan serves as a case study to test this theory. Japan, in particular, is a democracy where populism has the potential to succeed. Since the 1990s, Japan’s economy has observed at best tepid growth. More recently, South Korea, whose economy developed later than Japan, has achieved a higher nominal GDP per capita. Not only has Japan’s economic status been shaken, but its weakening yen has also spurred an unfamiliar and trying experience of inflation for its electorate.

Although Japan lacks the presence of an immigrant population large enough to fuel nativist sentiments, democracies with similar ethnic compositions, such as Hungary, show that this alone does not preclude the influence of populism; economic ills can suffice to trigger populist support. Why, then, has populism had a relatively limited impact on elections in Japan?

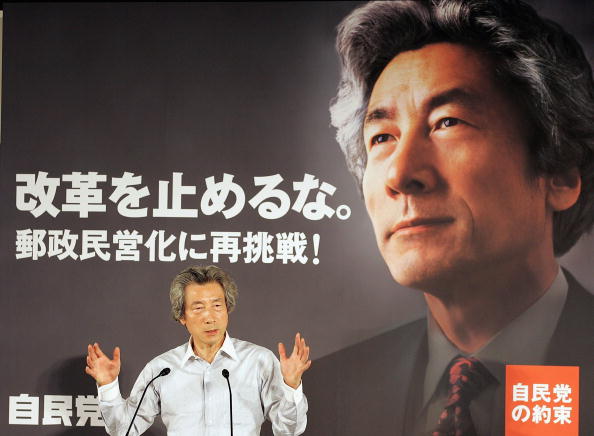

One factor may be that local, organized support retains its electoral clout. My SRG research identified two sources of evidence for this. First, I revisited an episode of populism in national politics in 2005, when then Prime Minister Jun’ichiro Koizumi from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) dissolved the lower house of the National Diet and called for an electoral referendum to overturn the upper house’s rejection of his postal privatization bill. The landslide victory demonstrated the potential for populism in Japan, as Koizumi’s anti-elite framing of opposition within his own party—as “forces of resistance” (teiko seiryoku) pursuing “vested interests” (kitokuken)—succeeded in reversing trends in falling voter turnout and secured a two-thirds majority for the LDP and coalition partner Komeito.

Prime Minister Koizumi announcing his party’s election platform calling for the privatization of postal services. ©Junko Kimura / Getty Images

Notably, though, the contests were especially challenging in divided districts where LDP candidates, mostly new blood, were assigned to compete against ex-LDP incumbent candidates who had opposed the postal bill and been stripped of their party’s endorsement.

Even though 51 LDP lower house members resisted Koizumi’s postal bill, only 37 members voted against it, and they were either expelled or ordered to leave the party. The 14 others who abstained or were absent from the vote retained their party affiliation (Shukan Asahi 2005; Asano 2006). Among the 37 who lost their LDP affiliation, 34 ran in the election, and exactly half were reelected.

Analyzing voting patterns across municipalities, I found a negative relationship between the LDP’s organizational strength and its vote gains. Specifically, in areas where the LDP was organizationally stronger, countermobilization by politicians in those districts drew significant votes away from the party. Even though Koizumi’s market-oriented postal privatization policy aimed to benefit urban voters by promoting productive investment, postal opposition candidate Seiko Noda, for example, successfully drew votes away from the LDP, winning reelection in Gifu’s first district covering the prefectural capital of Gifu City.

In another case, Ryozo Ishibashi, an LDP prefectural assembly member in the city of Hiroshima, entered the lower house race to oppose postal privatization and split LDP votes, drawing support away from the party in his district.

By contrast, in districts where the LDP was organizationally weaker and local conservative politicians had for several years been distancing themselves from the LDP, the decisions by these local mobilizers to support postal reform led to large increases in vote share, such as in Shizuoka’s seventh district.

Populism’s Impact on the 2024 Election

Second, I examined populism’s potency in the most recent lower house elections in October 2024 through an online survey experiment involving respondents from all 47 prefectures in Japan. In the survey, respondents were presented with a description referencing recent episodes of the political funds scandal, followed by hypothetical campaign excerpts from a non-LDP conservative candidate.

Respondents were randomly assigned one of two possible campaign messages. The first adopted a populist frame linking current economic woes to the collusive and corrupt LDP politicians who served vested interests over the interests of the people. The second similarly emphasized current economic woes but stressed party turnover and a change of government to strengthen policies as the solution. After reading the message, respondents were asked to indicate their support for the hypothetical candidate.

The experiment yielded evidence for the strong role played by local party representation, that is, the incumbent party’s organizational reach in local areas and role in politically fulfilling local needs.

First, the experiment found higher candidate support when respondents were exposed to populist messaging. This trend was stronger among respondents reporting weaker trust in political institutions, a pattern similar to that of populist support in European countries. However, unlike in Europe, populist support was not particularly strong among respondents residing in areas facing demographic decline or among those reporting economic insecurity in rural areas.

Instead, populist support was stronger among respondents reporting stronger feelings of representation at the municipal level and whose municipal representatives were non-LDP politicians. It was also stronger in prefectures with lower ratios of LDP party membership for each single-member electoral district.

Additional questions examining respondents’ attitudes revealed higher levels of nativist sentiments—where respondents perceive foreigners as a threat to local culture—in municipalities with higher ratios of foreign to local residents. This relationship is distinct from the inflow of tourists, which does not fuel nativist sentiments.

Importance of Local Organizations in Resisting Populist Rhetoric

These results suggest that the lack of populist support in Japan is not the result of unique resistance against the phenomenon but the geographical strength of its incumbent party organization. The idea that political party organization matters is not new to political science research (e.g. Katz and Mair 2018). But the results here reveal how, and in what ways, the incumbent party organization matters against the populist challenge.

My research also shows that the penetration of political party organizations in local electoral districts facilitates countermobilization and increases voter-level resistance against empty populist rhetoric that is devoid of policy relevance. This finding complements studies in other democracies that have identified the important effects of local mobilization but have emphasized the mobilizational effects of populist forces, such as in Sweden (Loxbo 2024).

The local electoral arena remains a salient theater for competition between incumbent and challenger parties. Ideological competition among central parties using party platforms and ideology is not a democratic ill. However, vulnerability to populism grows when attention at the center eviscerates the party of its local organization and overlooks the local arena.

This is not to imply that Japan presents a model of healthy democracy. Rather, it shows that populism, as an anti-elite appeal to majoritarianism, arises from not only commonly cited economic factors but also weak incumbent political party organization.

More broadly, there has been increased scholarly attention to the role of social media, warranted by increased reliance on information received through these platforms. Yet, even if social media has become the primary battleground for the electoral offensive, local areas remain critical flanks where electoral organization and representation matter. Strengthening these local organizational structures is essential if mainstream parties in countries like Japan wish to pursue electorally challenging policies, such as expanding immigration inflows.

References

Asano, Masahiko. 2006. Shimin shakai ni okeru seido kaikaku: Senkyo seido to kohosha rikuruto. Keio University Press.

Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair. 2018. Democracy and the Cartelization of Political Parties. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199586011.001.0001.

Loxbo, Karl. 2024. “How the Radical Right Reshapes Public Opinion: The Sweden Democrats’ Local Mobilisation, 2002–2020.” West European Politics 0 (0): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2024.2396775.

Roberts, Kenneth M. 2015. “Populism, Political Mobilizations, and Crises of Political Representation.” In The Promise and Perils of Populism: Global Perspectives, edited by Carlos de la Torre, 140–58. University Press of Kentucky.

Shukan Asahi. 2005. “Jiminto zohan 51 giin, kaisan de konaru: Koizumi dokatsu hatsugen no daigosan.” August 5.

Urbinati, Nadia. 2019. “Political Theory of Populism.” Annual Review of Political Science 22 (1): 111–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-070753.

Weyland, Kurt. 2001. “Clarifying a Contested Concept: Populism in the Study of Latin American Politics.” Comparative Politics 34 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/422412.