Voices from the Sylff Community

Mar 7, 2025

In Search of Women Photographers in Twentieth-Century India

Exploring the largely hidden history of early women photographers in India, Sreerupa Bhattacharya (Jadavpur University, 2018) follows traces of their work to uncover the contributions they made in shaping the art and practice of photography on the subcontinent.

* * *

In an 1898 issue of Amrita Bazar Patrika, one of the leading daily newspapers in colonial Bengal, appeared an advertisement for a well-known photo studio, emphasizing the availability of “female artists” to photograph women. A lady behind the lens meant that elite women could have their photographs taken without inviting anxieties about being seen unveiled by men in public. It is, however, not known if these “artists” were necessarily only photographers or also those involved in tinting and retouching photographs.

Notwithstanding, it is significant that photography emerged as a source of employment for European as well as native women at the turn of the twentieth century. When the first all-women’s studio in India was established in 1892 to exclusively serve a female clientele, it recruited “native female assistants” who were led by an Englishwoman. These examples attest to women’s prolific presence in a range of photographic works at a time when they were yet to become key players in the many other technology-led industries in colonial India.

My doctoral research examines women’s photographic practices in early- to mid-twentieth-century India and their rediscovery in contemporary times, with a focus on questions of labor, materiality, and representation. Recent curatorial and scholarly interests in twentieth-century Indian women behind the lens have largely focused on family and domestic photography. My project seeks to build on this scholarship by moving away from the biographical approach and mapping individual practices onto the larger discourse of photography. The purpose is not only to recover little-known lives and their contributions but also to expose marginalized objects, sites, and networks through them in order to potentially reconfigure the photo history in the subcontinent and expand our understanding of photography in turn.

Footnotes in Photo History

Women, until recently, have been footnotes in the grand narrative of the history of photography in India that has mainly dramatized the conflict between the colonizer and the colonized, emphasized the peculiarly Indian character of photography, and celebrated its pioneering male figures. The “native female assistant” remained nameless, for instance, in the several monographs on the work of Lala Deen Dayal, the eminent photographer who established the photo studio in which these women worked.

In his 2008 book The Coming of Photography in India delineating the sociocultural, political, and philosophical implications of the arrival of the camera under the Raj, art historian Christopher Pinney mentions a set of calotypes and photograms by an unknown female photographer. Made in the 1840s, they are significant as the earliest extant photographs of India. Yet, she receives no more than a passing reference. Perhaps no more than that is possible since institutional archives bear only traces of such women’s presence.

Rather than bemoan such absences, my project explores them as speculative nodes to flesh out the figure of the woman behind the lens. One of the imperatives of the project, thus, is to delineate the discursive forces, historically and in the contemporary, that have constituted the figure of the woman photographer in India.

New Insights from Revisiting the Archives

Many of the photography journals, pamphlets, and illustrated magazines published in twentieth-century India are currently housed in institutions across the United States and Europe. Perhaps the most capacious among these is the British Library in London, where Desmond Ray, the deputy keeper of the India Office Library and Records, consolidated in the 1970s and 1980s both images and documents related to photography in India.

The Sylff Research Grant allowed me to explore the British Library collection in great detail during my two-month-long stay in the UK. The other archives and institutions I visited included the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Cambridge South Asia Centre, Birkbeck College, the University of London, and the Courtauld Institute of Art. In each of them, I found librarians, archivists, and professors who provided extraordinary insights into my project, greatly enhancing my understanding of the nebulous photographic landscape in India and in other parts of the world in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

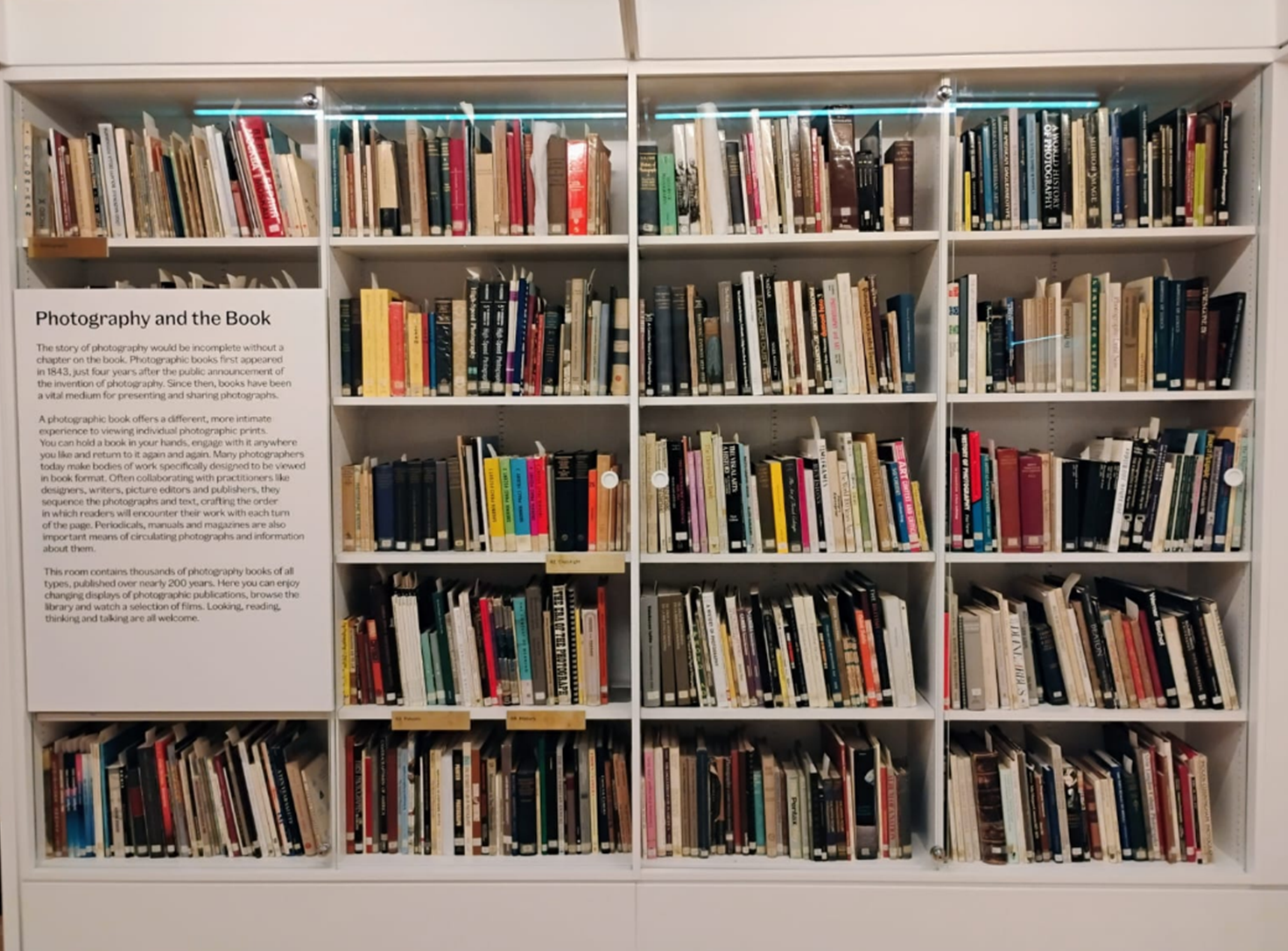

The Photography and the Book Room of the Photography Centre, Victoria and Albert Museum, September 2024. Photo by the author.

Parsing through different kinds of documents—letters, periodicals, photographs, and news reports—led me to glean names of individuals, organizations, and activities that suggest a scattered but persistent presence of women photographers. They reveal new constituencies of photo practitioners that expand the contours of received histories.

Departing from the recent focus on amateur practices centered on the family, home, and travels, my archival research revealed a discursive emphasis on photography as an occupation for women throughout the twentieth century. Photography emerged as one of the few technology-led activities that could easily make the transition from pastime to profession.

Women photographers thus marked their presence in photo studios, at political rallies, in exhibitions, and behind editorial desks. With cameras in hand, they not only made aesthetic interventions but also exposed the fault lines in the discourse of photography. While much of contemporary scholarship revolves around individual practices, revisiting the archives enabled me to reorient the focus to a matrix of material relations that reveal the history of photography in India as gendered work.

From the series Centralia, 2010–2020, by Poulomi Basu, on display at the Photography Centre, Victoria and Albert Museum, October 2024. Photo by the author.

A Global Phenomenon

Besides conducting archival research, I was fortunate to be able to participate in workshops organized by scholars, artists, and critics at the forefront of global photography studies today. A joint initiative by the Victoria and Albert Museum and Birkbeck College for doctoral students called “Researching on, and with, Photographs” proved invaluable in exploring the wide range of contemporary scholarly work on the political and aesthetic purchase of historical photography. A talk on British photographer Jo Spence’s collection was insightful in thinking about feminist articulations of art and activism. It also raised questions about how to preserve and display such works, meant for public engagement, within formal institutional structures.

The sessions held at the V&A Photography Centre also offered glimpses into the early processes in the development of photography, the formation of the institution’s photography collection, and its current decolonial efforts. It gave me the opportunity to discuss the museum’s recently developed women in photography collection, which contains a wide range of photographs made in the British colonies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The workshop and the ongoing projects at the museum foregrounded the renewed interest in the study of women behind the lens. Just in the past five years, there have been major conferences and exhibitions on twentieth-century women photographers in North America, Europe, and Asia. My project gains greater resonance amidst such efforts at rediscovering and reevaluating twentieth-century women’s photography around the world.

Comments

Other

It is fascinating to see how a visionary sholarship programme like SYLFF that provides infinite opportunities to fellows to unleash their creative mind. I wish as envisaged in the sylff goal SYLFF-fellows can become true global leaders for building peace and harmony and better future for humanity. -Joyashree Roy, March 27, 2025-