Nemanja Vuksanovic, who received a Sylff Research Award grant in 2021, conducted an empirical analysis of the economic role of education in the labor market and unequal opportunities in education in the Central and Eastern European countries. While policy makers in these countries need to increase the availability of higher education, financial resources must be primarily directed to the poorer segments of society, notes Vuksanovic; over-subsidizing post-primary education could increase income inequality rather than reduce it.

* * *

Subject, Aim, and Motivation

The subject of my research was the analysis of the economic role of education in the labor market, observed from the aspects of human capital theory and signaling theory, as well as the analysis of unequal opportunities in education in the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries. The aim was to empirically determine the extent to which, in the CEE countries, education improves productivity or represents a characteristic that signals productive capabilities, as well as to empirically examine the degree to which selected countries are characterized by unequal educational opportunities.

There are several basic motivating factors for choosing the research topic.

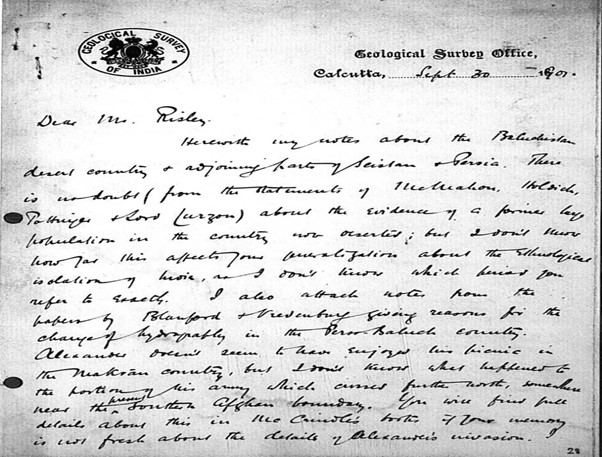

Firstly, this research contributes to the development of scientific and professional literature related to the economics of education in the CEE region. It is pioneering research that addresses the economic role of education in the labor market and unequal educational opportunities among the CEE countries. No attempts have been made thus far to evaluate the premium on education, the effects of diplomas, and the influence of factors limiting the achievement of a certain educational level in this region by means of the proposed theoretical and methodological framework. I chose this topic because this research can contribute to a better understanding of the transition paths of Serbia and selected CEE countries in the segment related to the educational process.

Secondly, the research conducts a detailed and systematic overview of theoretical models developed to explain the economic role of education and unequal educational opportunities, by looking at the historical development of these models and the most significant results of previous research. Special emphasis is given to describing the problems that researchers encounter in empirical studies when assessing the rate of return on investment in education and the effects of diplomas. In a broader context, the significance of the research lies in general contribution to the development of scientific and professional literature in the field of economics of education. My intention was to present through the research an appropriate theoretical and methodological framework for future research on topics in the domain of this economic field.

Another scientific contribution of the research lies in the empirical results, which could help policy makers in the CEE region to create a more complete picture of the education system and, based on that, to develop guidelines for improving the education process. The findings of the research should make more visible the problem of inequality in income distribution, which arises from circumstances beyond the control of the individual. The study of unequal opportunities in education has gained in importance in recent years as a result of the increasing attention that researchers are paying to the problem of income inequality. The study of factors limiting equitable access to education is important because it can clarify the effects of education as a mechanism for reducing inequalities in income distribution. So my main motivating factor is that the research results can provide a better understanding of the segment of demand for education and distribution of education and be helpful to education policy makers among the CEE countries.

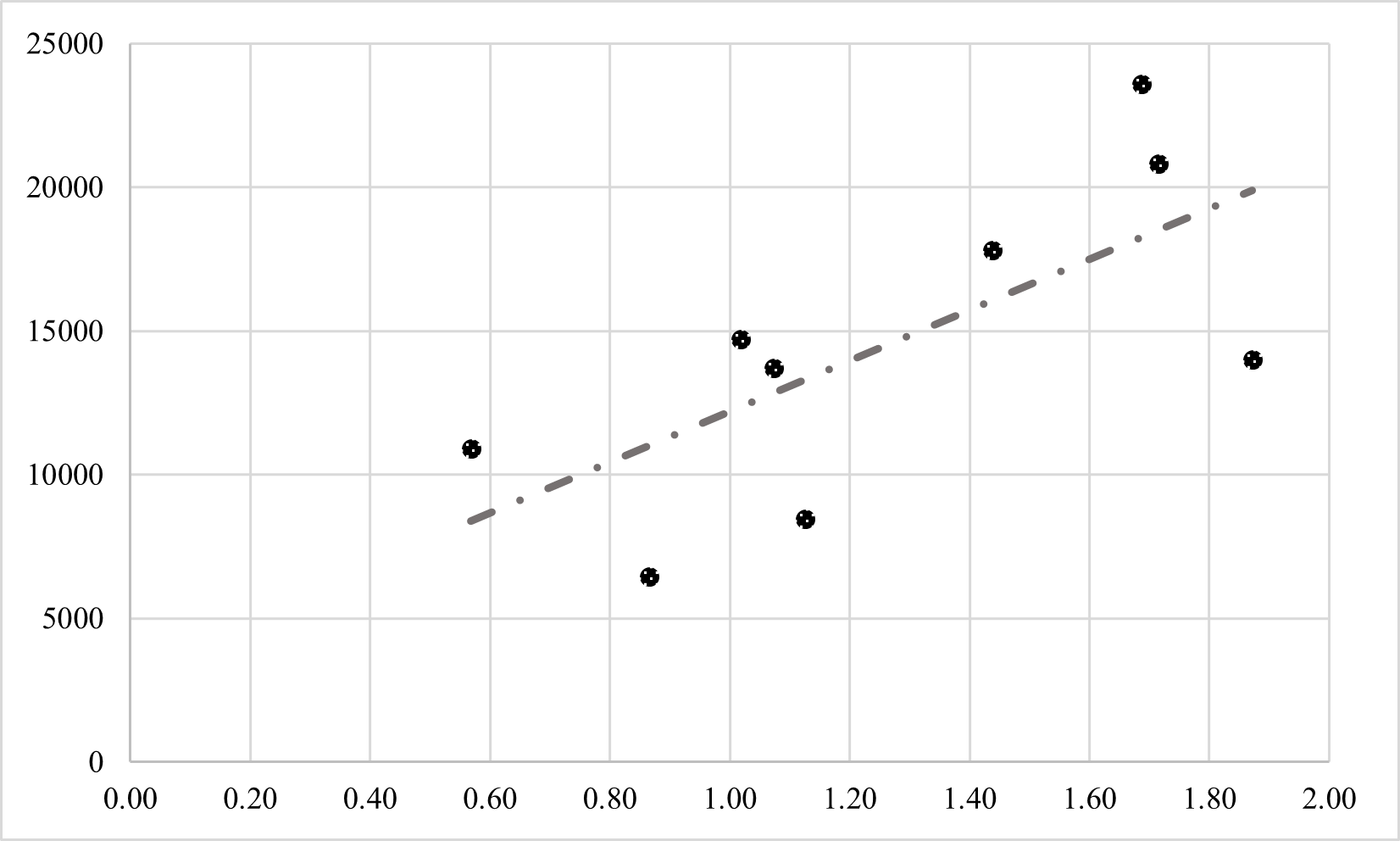

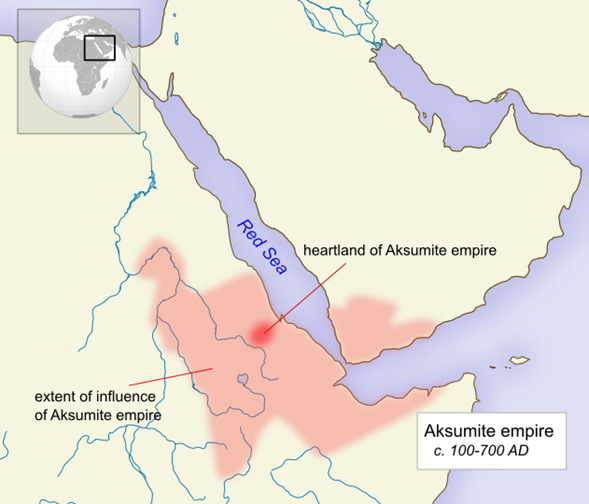

Figure 1. Relationship between ratio of share of high-educated and share of low-educated population (x axis) and GDP per capita (y axis) among CEE countries

Basic Findings and Public Policy Implications

Seen from the social aspect the significance of the research results is manifold, since it can provide several guidelines for policy makers.

The results of my empirical study assessing the rate of return on investment in education indicate that in all CEE countries the positive return on investment in tertiary education is higher than the negative return on investment in primary education. That is, the link between education and earnings is convex, suggesting that in the CEE countries the highest rate of return is tied to the highest level of education. This tendency of the rate of return on investment in education—whereby the premium on education does not decrease with educational levels, so that it is highest in primary and lowest in tertiary education—has already been noted in a number of other studies.

In all CEE countries apart from Hungary, the positive premium on higher education is six to nine percentage points higher than the negative premium on primary education. points out that the relatively high rate of return for tertiary education may be because rates of return on investment in tertiary education are higher in those countries where the supply of more educated individuals grows at a slower pace than the demand for such individuals. Acemoglu (2008) argues that the gap in supply and demand for highly educated individuals may reflect the specificity of the country’s institutional framework or differences in changes in the openness of the economy and changes in the field of technological progress. Consequently, the present gap may have negative implications for the country’s economic development, as it leads to underutilized human resources. This implies that a country like Serbia, where the rate of return on investment in tertiary education is among the highest in the CEE region, is characterized by a significant gap in supply of and demand for highly educated individuals. This situation indicates the need for policy makers in Serbia to take appropriate measures to increase the supply of highly educated people.

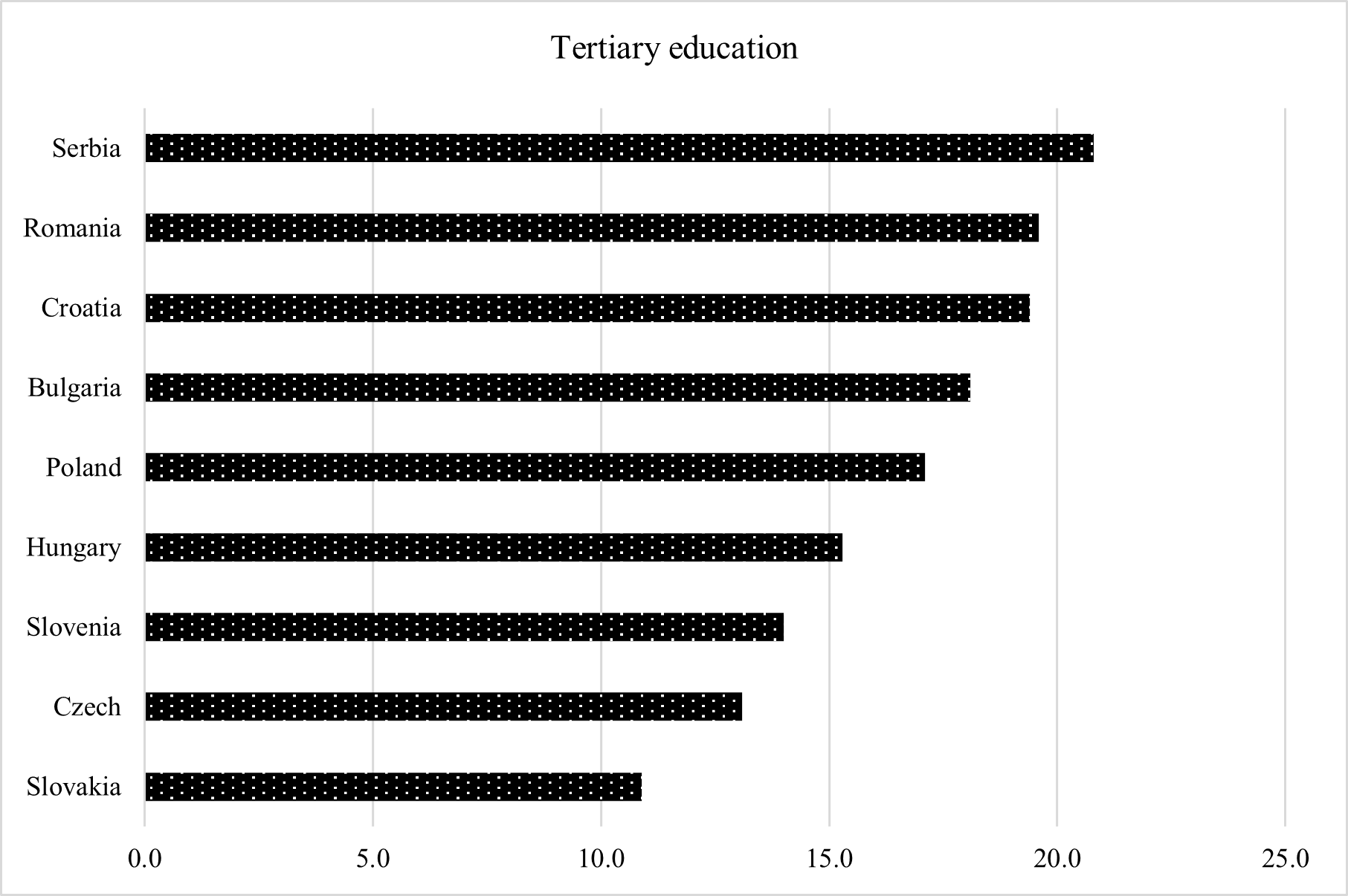

Figure 2. Returns to high education in CEE countries

For policy makers, the observed pattern of returns on investment in education in CEE countries may also mean that a significant rise in the percentage of the population with lower levels of education will not greatly increase the earnings of individuals with these levels of education. The convex link between education and earnings suggests the possibility that over-subsidizing post-primary education may increase rather than reduce income inequality. Many international agendas, such as the Millennium Development Goals, have focused on increasing the share of the population with primary education. But when the link between education and earnings is convex, public investment aimed at increasing the coverage of the population with lower levels of education will not significantly increase the earnings of low-educated individuals. Moreover, Schulz (2003) points out that in countries where public subsidies in tertiary education are high—as is the case in many African countries—the convex link between education and earnings means that large amounts of public transfers to individuals in higher education, if not targeted, benefit most those whose families are of better socioeconomic status. In this case, such a public policy will not be very effective in reducing inequalities in income distribution. Both facts indicate that a successful public policy in Serbia must be directed toward more efficient allocation of educational investments; in other words, that special attention must be paid to distributing these investments by levels of education and targeting appropriate socioeconomic groups.

The results of the second empirical study show that every additional year of schooling over the years necessary for obtaining a university degree has a negative effect on earnings. This finding has significant implications for education policy. If some individuals benefit more from gaining a certain level of education, then policy makers need to recognize such different influences. This is especially important in the case of less developed countries of the CEE region, such as Serbia, where children from families of lower socioeconomic status face greater financial constraints. Namely, when education plays the role of a signal, it is important that highly gifted individuals be able to reach the highest levels of education to prevent the quality of the signaling role of education in the labor market from collapsing. Caplan (2018) points out that excessive public investments in education that are not directed toward appropriate groups devalue the importance of the role of education as a signal. Generous and untargeted public investment in the education system may jeopardize the importance of education as a means of overcoming the problem of information asymmetry between workers and employers. A nonselective policy of over-subsidizing higher education could lead to inflation of diplomas, which would greatly weaken the role of education as a signal. This is especially true in Serbia and Romania, where the signaling role of education is relatively weak among the CEE countries. Public policy makers in Serbia and Romania must therefore take care that financial resources are primarily directed to children from poorer families, with a focus on the talented ones, so that those children can reach the highest levels of education.

Improving the availability of higher levels of education through increased and well-targeted public investment is particularly important given the results of the third empirical study, which indicate the existence of unequal opportunities in education among the CEE countries. Increasing the proportion of the population with higher education may represent an appropriate public policy aimed at reducing income inequality, in line with the demonstrated link between education distribution and wage distribution. Pikkety et al. (2020) point out that this is important because the significance of implementing appropriate predistribution measures has recently been emphasized in the international agenda. Predistribution, which can influence the distribution of income before redistributive measures—taxes and social transfers—take effect, is based on the view that a country’s institutional framework through the legal and social system can contribute to reducing income inequality. Appropriate public policy in the CEE countries should be aimed at increasing the availability of higher education, while care must be taken to ensure that this coverage primarily affects individuals of lower socioeconomic status. A well-targeted predistribution policy oriented toward creating a fairer education system and a society characterized by equal opportunities can contribute to the country’s economic development and to the reduction of poverty and income inequality.

References

Acemoglu, D. 2002. “Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market.” Journal of Economic Literature 40, no. 1 (March 2002): 7–72.

Caplan, B. 2018. The Case against Education: Why the Education System Is a Waste of Time and Money. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Piketty, T., A. Bozio, B. Garbinti, J. Goupille-Lebret, and M. Guillot. 2020. “Predistribution vs. Redistribution: Evidence from France and the U.S.” WID.world Working Paper, 10.

Schultz, T. P. 2003. “Higher Education in Africa: Monitoring Efficiency and Improving Equity.” In African Higher Education: Implications for Development, 93. New Haven, CT: The Yale Center for International and Area Studies.