Digital threats like online lending and gambling are on the rise in Indonesia. An SLI-supported digital resilience project led by Obby Taufik Hidayat (Universiti Malaya, 2023) offers strategic solutions through education, community collaboration, and policy reform to protect vulnerable groups in West Java.

* * *

In today’s interconnected world, rapid advances in digital technology have revolutionized numerous aspects of our lives, including communication, commerce, education, and social interaction. However, this digital revolution also brings significant challenges, particularly in the form of digital threats, such as cybercrime, identity theft, digital fraud, and cyberbullying. These threats compromise the security and privacy of individuals, posing a significant risk to the stability and well-being of communities worldwide. Addressing these issues requires proactive and comprehensive strategies that empower individuals and communities to navigate the digital landscape safely and effectively.

The alarming increase in online lending in West Java is a pressing issue that underscores the importance of such strategies. By early 2024, total debt from online lending in the region had reached a worrying IDR 16 trillion. This significant financial burden indicates broader digital vulnerabilities faced by communities. Many individuals, particularly those with limited financial literacy, fall victim to predatory lending practices and digital fraud associated with online lending.

The ease of access to quick online loans, combined with a lack of understanding of terms and conditions, often leads to debt cycles and financial instability. Additionally, the digital nature of these transactions makes it easier for fraudulent actors to exploit unsuspecting borrowers, exacerbating the problem further.

The Building Digital Resilience program that I initiated is aimed at addressing these challenges by providing communities with the knowledge, skills, and resources necessary to combat digital threats. This initiative aligns with the Sylff goal of identifying and nurturing leaders who can transcend differences in nationality, language, ethnicity, religion, and political systems.

By enhancing digital literacy and resilience, the program seeks to empower community members to safeguard themselves and others against digital threats, thereby fostering safer and more secure societies.

The primary objectives of the Building Digital Resilience program are to raise public awareness, foster digital literacy, promote safe online practices, enhance community collaboration, and empower vulnerable groups.

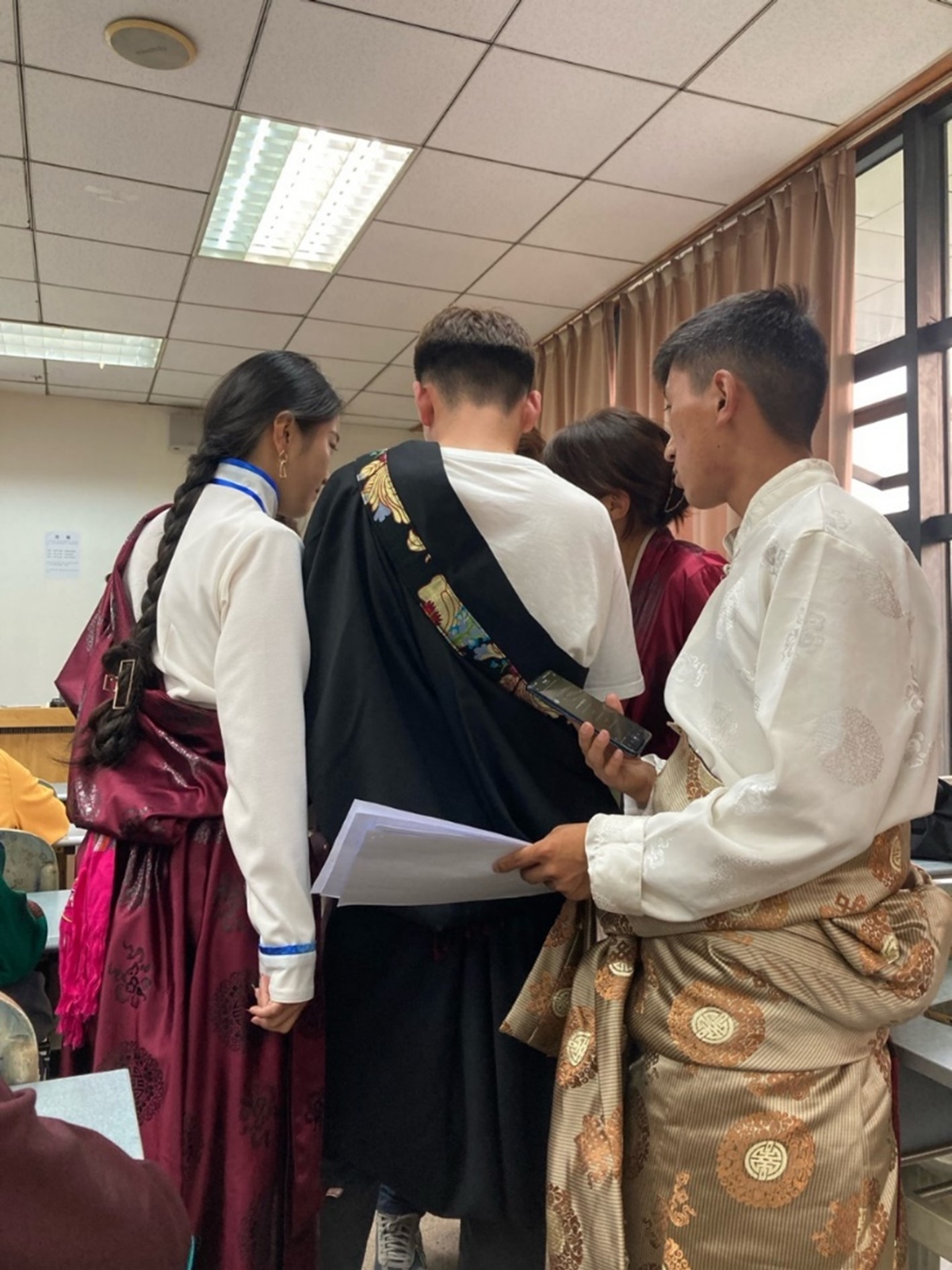

The official launch of the SLI project was held at Bandung Creative Hub and was attended by a diverse group of teachers and students.

Specifically, the program conducts workshops to raise awareness about digital threats, develops online resources to provide ongoing digital literacy education, and runs campaigns to encourage safe online behavior. Additionally, partnerships are being established with local schools, community centers, and nonprofit organizations to broaden the program’s reach and impact.

Digital Portrait of Indonesia: Findings from Various Social Strata

This project was launched at a Kick-Off event in Bandung, followed by educational visits to elementary schools, junior high schools, senior high schools, and community centers. At the high school level, activities were conducted at five schools in the Bandung metropolitan area and one in Bogor Regency.

During these school visits, students demonstrated varying levels of engagement and understanding in response to the activities. Those from densely populated areas with lower-middle-income backgrounds tended to be more passive. According to one teacher, this may be due to economic hardships and challenging family circumstances.

Conversely, students from upper-middle-income environments responded enthusiastically and demonstrated a range of cognitive engagement, actively asking questions and adopting a critical attitude, as evidenced by the exceptionally lively responses during the gamification session.

An interactive gamification activity at a senior high school.

Teachers at a senior high school in Bogor Regency showed high interest in this project, as evidenced by their invitation to collaborate on the school’s podcast. This indicates that many teachers are also grappling with digital issues and recognize the need to enhance their digital literacy. The differences observed among schools highlight the impact of socioeconomic disparities on digital resilience, suggesting the importance of tailoring interventions to specific individual and community contexts.

Group photo at a junior high school following a series of engaging activities.

At the junior high and elementary school levels, the activities proved to be quite energy intensive. Participants at junior high schools, particularly those affiliated with Islamic boarding schools, were observed to be passive and lacked adequate digital literacy, despite the inclusion of computer science in the curriculum. This highlights the gap between formal education and practical digital literacy skills.

In the elementary schools visited, which were often located near marginalized residential areas, most activities were filled by fifth-grade students. Despite some students having limited reading and writing skills, many were actively engaged with the digital world, though often in ways considered inappropriate, with reports of some accessing harmful content, such as online gambling sites.

Pre-activity bonding interactions with students at a primary school.

According to one teacher, this behavior is influenced by the family environment, with many students imitating family members who engage in online gambling. One concerning finding was that nearly 80% of the elementary school students in these areas come from divorced families, which results in limited digital supervision at home. A low understanding of digital dangers makes children more vulnerable, and family instability further creates a void in parental supervision.

In one densely populated village in Bandung, residents were found to be actively involved in online gambling and quick loan schemes. A neighborhood association leader expressed serious concern about the illegal collection of funds, suggesting that these digital activities may be fostering corruption—or perhaps are themselves driven by corrupt practices. This finding highlights the intricate link between digital financial risks, socioeconomic status, and unlawful activities, including corruption.

Group photo with local community members in a densely populated area of Bandung Regency.

International Dissemination of the SLI Project

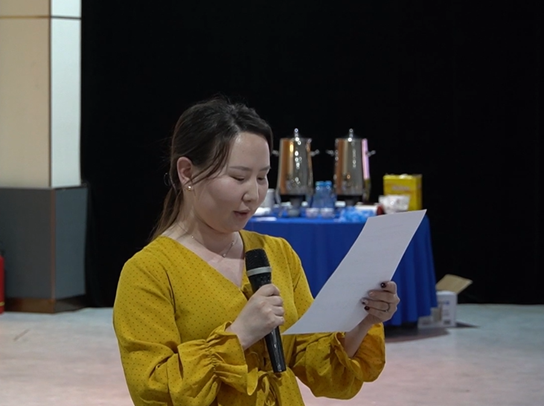

Another important aspect of the SLI project was the dissemination of its outcomes by the fellow at the 13th European Conference on Education, organized by the International Academic Forum (IAFOR), held in July 2025 at University College London, United Kingdom. The fellow received valuable feedback through knowledge exchange with academics from various countries, which contributed to achieving the objectives of the SLI project: enhancing digital literacy and cybersecurity awareness.

Presenting the results of the Building Digital Resilience project at IAFOR 2025.

Ronald William, a PhD student from Japan, provided insights into online gambling and other cybercrimes, saying that in Japan, the focus is not on eliminating gambling in general but on educating children from a young age to develop moral character and ethical self-awareness. He also noted that Japan has stringent financial transaction rules. Both domestic and international bank transfers, for example, require detailed and precise information. As a result, digital financial transactions in the country are well-protected.

Scholars from Italy shared their expertise in digital literacy education and cybersecurity awareness through project-based learning. According to them, this approach effectively enables students to apply the theories they have learned in the classroom in real-world settings, resulting in numerous insights that bridge theoretical knowledge with practical experience. This reflective process fosters the development of new knowledge that benefits both students and the community, enhancing digital literacy and cybersecurity awareness.

There was also significant input from Puan Siti, a scholar from Sabah, Malaysia. She noted that strict government regulations in Malaysia, such as those aligned with Islamic prohibitions against online gambling, encourage widespread community compliance. For example, ethnic Malays who are Muslim tend to fully adhere to these rules without the need for additional persuasion. As a result, access to online gambling is limited among the Malaysian public, especially those who are Muslim, who are also guided by strong religious principles.

Many other suggestions were made at the UK conference that may prove valuable for policymakers in Indonesia in addressing online crimes. These recommendations are summarized in the section below.

The Focus Group Discussion and Digital Resilience Workshop examined the information gathered during the school visits and explored opportunities for continued development.

The Focus Group Discussion and Digital Resilience Workshop examined the information gathered during the school visits and explored opportunities for continued development.

The results of this SLI project show profound policy implications for building digital resilience in Indonesia. Digital social deviance, such as online gambling addiction, is a growing issue that affects individuals across various socioeconomic backgrounds. While low-income groups are often targeted with promises of instant wealth, those from middle- and upper-income backgrounds may also engage in risky digital behaviors due to easy access to technology, limited digital literacy, peer and family influence, and such psychological needs as stress relief.

In schools, teachers and administrators play a crucial role in addressing digital deviance. However, many lack the necessary capacity, training, and policy support to effectively prevent or respond to these challenges.

Existing curricula, especially at the junior high school level, do not explicitly incorporate digital literacy, leaving schools to rely on informal programs, such as extracurricular activities or project-based learning. The heavy administrative burden on teachers further limits their ability to take on additional responsibilities related to digital risk prevention.

A multi-sectoral strategy is essential for building digital resilience. The pentahelix model, which brings together government, schools, families, communities, and academia, provides a framework for shared responsibility and collaboration. Parents need to be equipped with digital parenting skills, schools must integrate digital literacy into formal education, and governments are responsible for creating policies, providing resources, and establishing reporting mechanisms to combat harmful content. Community environments should also foster positive digital behavior through collective norms.

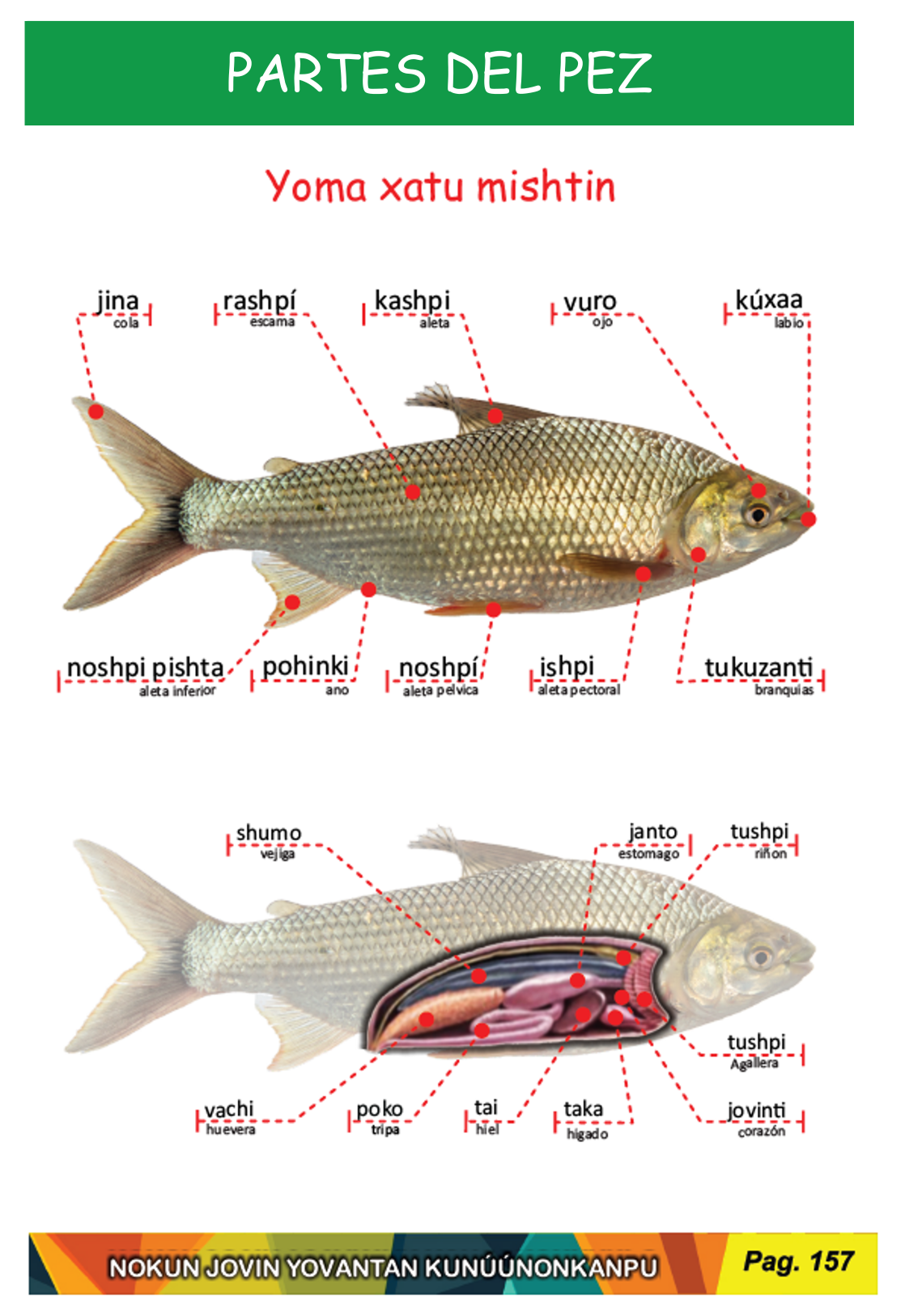

The Digital Resilience Education (DRE) module offers a structured approach to improving students’ ability to navigate the digital world safely. However, its implementation must be adapted to different educational levels, local cultures, and student needs. In primary schools, the focus may be on raising awareness, while at higher levels, the emphasis should shift toward developing critical thinking and digital self-control. Using Indonesia’s many local languages may enhance the relatability of messaging in specific regions. Nevertheless, external challenges persist, particularly family norms and peer influences that normalize deviant behavior.

The findings of the SLI project on Building Digital Resilience in West Java highlight the urgent need for a comprehensive strategy to address digital threats and promote digital literacy, especially among young people. Tackling socioeconomic disparities and integrating digital education into the school curriculum will be essential for creating a safer digital landscape. By adopting international best practices and fostering cooperation among educators, policymakers, and communities, Indonesia can build a more resilient digital society that protects vulnerable groups and promotes responsible, ethical online behavior.