Izabella Deák (Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2025) explores how authoritarian regimes exploit concepts like sovereignty and identity to restrict the activities of civil society organizations, undermining democratic processes and limiting public participation in decision-making.

* * *

In Hungary, a new law aimed at restricting the activities of civil society organizations (CSOs) that receive foreign funding came into effect in 2023. Called the Law on the Protection of National Sovereignty, it establishes the Sovereignty Protection Office, which holds extensive investigative powers. The Office’s main task is to uncover and investigate activities carried out on behalf of other states, foreign bodies, organizations, or natural persons that could potentially violate or endanger Hungary’s sovereignty.

The Office pays special attention to activities aimed at influencing democratic debate and the decision-making processes of persons exercising public authority. It also identifies and investigates organizations that use foreign funding for activities that may influence election outcomes or voter will.

The Office can access data of the investigated organization or individuals, including sensitive personal data, allowing for unlimited data collection. It is important to note that the law does not provide for legal remedies against such procedures, which raises serious concerns from a rule of law perspective. If the Office’s investigation reveals irregularities that require further action (such as misdemeanor, criminal, or administrative procedures), it notifies the competent authorities.

Undermining Democratic Public Life

The law lacks precise definitions of key concepts like sovereignty and advocacy activities, leaving room for arbitrary interpretation and application. This allows the Office to potentially investigate anyone suspected of serving foreign interests or endangering national sovereignty.

A particularly concerning aspect of the legislation is that the Office can investigate activities aimed at influencing democratic debate and public decision-making. This provision could potentially suppress dissenting opinions and discourage citizens from actively participating in public affairs. Freedom of expression and the right to participate in decision-making are closely linked to the freedoms of association and assembly, which form the basis of CSO operations. Restricting these rights also jeopardizes the right of CSOs to raise their voices and represent the communities they serve. Thus, the law is capable of undermining democratic public life and social publicity by stigmatizing and intimidating citizens and CSOs active in public affairs.

The Office is producing reports on an increasing number of CSOs and adding more to its lists with the intention of stigmatizing them.

The representatives of the organizations forming the Civilization coalition, an alliance established in Hungary in 2017 to enable CSOs to jointly stand up against the government’s oppressive efforts.

The outlined restriction on civil society organizations is not an isolated case. The number of laws restricting the establishment, operation, and activities of CSOs that perform social control functions is increasing year by year. The rise in the number of restrictive laws is closely linked to the expansion of authoritarian systems. The reason for this lies in the nature of the social control function. These organizations draw attention to the very irregularities that characterize an authoritarian government: anomalies in the system of checks and balances, state corruption, personal conflicts of interest, and, not least, human rights violations.

CSOs performing social control functions can be classified, on the one hand, as watchdog, advocacy, and human rights organizations. Through their role in monitoring and counterbalancing power, these organizations serve as guarantees of democracy. Their activities can influence public policies, promote the enforcement of rights, and highlight the interests of marginalized or minority groups. Additionally, they strive to create and redistribute economic, social, and political capital for marginalized groups.

On the other hand, there are also CSOs whose services are inseparable from representing the interests of their target groups (such as the poor, the disadvantaged, or the homeless) or whose cultural activities are inherently tied to advocating for the recognition of minorities. In these cases, even if CSOs do not directly engage in advocacy and the protection of rights, they still play a significant role in shaping government policy.

Façade of Pluralism

Traditional autocracies are characterized by the prohibition of the establishment of independent CSOs, networks, and social circles. Systems resembling traditional autocracies today do not have an autonomous civil sphere either, as the state prevents the creation of independent CSOs. One notable feature of modern authoritarian regimes, though, is their avoidance of outright bans. They can appear pluralistic but actually implement only limited and superficial pluralism.

The freedom of civil society is constrained, for example, by heavy restrictions on spaces for public debate where state actions could be questioned.[1] In other words, modern authoritarian systems strive to exclude alternative opinions from public discourse.[2] This approach allows them to create the illusion of democracy while continuing to severely restrict genuine civil activity and independent expression of opinion. Behind the façade of pluralism lies a structure that effectively hinders the formation and operation of an autonomous civil sphere.

Therefore, modern autocratic efforts often lead to the erosion of autonomy, as reflected in measures against CSOs that perform social control functions.[3] A significant portion of such measures attempt to undermine the activities of CSOs through restrictive legislation that grants government actors a greater degree of control and oversight over the civil society sector, thereby violating the freedom of association of CSOs. The restrictions delegitimize the operation of CSOs, reduce their impact in the areas of human rights and advocacy, and threaten sanctions for violating the laws.

The restrictions on CSOs can be wide-ranging. They may relate to registration procedures for establishing CSOs and re-registration procedures. They can affect CSOs’ access to foreign funding, with laws intended to combat money laundering and terrorism being used against CSOs. They can increase the administrative burden on CSOs, hinder their collaboration with foreign CSOs, and limit their freedom of expression. Finally, they can extend to the unlawful dissolution of CSOs.

The protest organized by the Civilization coalition against the “Stop Soros” legislative package. The package targeted Hungarian CSOs that were involved in any form of work with asylum seekers and refugees.

Indicators of Democratic Backsliding

My research examines the aforementioned restriction mechanisms, with a focus on cases where countries reference their unique national culture and traditions to misuse concepts such as sovereignty, nation, or identity. The goal of this research is to explore how these restrictions reflect either a particularistic approach of the respective country or fit into a relatively uniform pattern. I also look at how particularistic approaches can be reconciled with universal legal standards and norms, such as the protection of human rights, the requirements of democracy, and the rule of law. The minimum standards developed by the European Court of Human Rights in its judgments relating to civil society organizations are used as a benchmark.

According to the research hypothesis, in most cases the seemingly particularistic interpretations of the concepts by authoritarian or authoritarian-leaning countries are not in line with universal constitutional principles. Because local approaches should remain within the frameworks defined by universal principles, restrictions on the fundamental rights of CSOs are acceptable only if they are in line with universal principles—that is, if they comply with the freedom of association that applies to everyone.

If these restrictions are specifically used to weaken the social control function, they violate the equality of CSOs before the law, since the CSOs performing social control functions will be unable to participate in the political public sphere to the same extent as other CSOs, and the freedom of association of their staff and members will be disproportionately impacted.

This, in turn, violates the principle of nondiscrimination, meaning it is contrary to universal constitutional principles. Laws and state authorities must treat CSOs equally in terms of rules regarding their establishment, operation, and activities. The differential treatment of various CSOs is considered discriminatory if it lacks objective and reasonable justification, as when such treatment does not pursue a legitimate aim or when there is no reasonable proportionality between the means employed and the objectives set.

Conversely, differentiation is permissible if it does not result in inequalities; in other words, if a particularistic approach is used, it must not be unjustifiably exclusionary. If the hypothesis is confirmed, discriminatory laws adopted by states that restrict the social control function can be viewed as an indicator of autocratization.

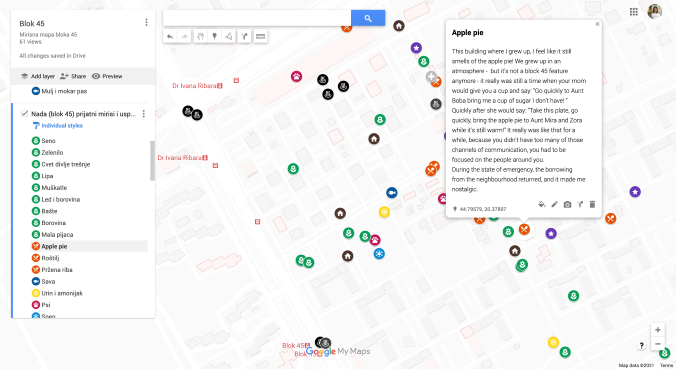

This research builds upon a previous empirical study that examined and categorized laws in effect between September 2022 and February 2023 in terms of specific restrictions on CSOs. My current research has two main objectives: to review the original data to determine which restrictions remained in force in 2023 and to expand the focus of research to include unlawful cases of CSO dissolution, where dissolution occurs by invoking vague concepts. The research is conducted using the comparative constitutional law method, with the following sources being analyzed to identify restrictive legislation: reports from the CIVICUS Monitor, Freedom House’s Freedom in the World, ICNL’s Civic Freedom Monitor, and USAID’s CSO Sustainability Index Explorer, as well as annual reports from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. The restrictions identified in these sources are verified against the relevant laws of the countries involved.

The chosen method aims to capture authoritarian tendencies by comparing the democracy index scores generated during monitoring procedures of various international organizations and research institutes. Therefore, I compare the identified restrictions with the democracy index classification of the countries applying these restrictions.

Specifically, I am creating a database containing the following information: which countries have laws that include restrictions causing the dysfunctionality of CSOs, what type of restriction involves the use of vague concepts, and into which category the countries in question are classified by the three democracy indices used as reference points (V-Dem’s Global Regimes of the World, Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index, and the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index). The indices’ reports published in 2024 contain the countries’ classifications for 2023, so the research period is also limited to the year 2023.

The goal of my research is to demonstrate that a characteristic feature of modern authoritarian systems is their exploitation of concepts such as sovereignty, nation, and identity for their own purposes. These regimes seek to restrict and ultimately eliminate the social control function as comprehensively as possible. Within such frameworks, the equality and freedom of CSOs performing social control functions become unattainable, despite the façade of democratic processes that contemporary authoritarian regimes often maintain.

[1] Andrew Arato and Jean L. Cohen, Populism and Civil Society: The Challenge to Constitutional (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 129.

[2] Guillermo O’Donnell, Phillipe C. Schmitter, and Laurence Whitehead, Transitions from Authoritarian Rule (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 48.

[3] Gábor Attila Tóth, “Constitutional Markers of Authoritarianism,” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 11, no. 1 (2019): 37–61.