Melinda Kovai, a 2009 Sylff fellow at Eötvös Loránd University in Hungary, and her team members have recently completed their SLI project, which took them over one and a half years, to address the problem of social disparity strongly linked to negative notions toward the “Gypsy.” The project incorporated the idea of reflection on one’s own social position to encourage understanding of different social groups, which contributed to the uniqueness of the project. The training materials, the final project product, have been already integrated into two courses at universities in Hungary. The project members hope that the materials will be utilized in many educational settings not only in Hungary but also in neighboring countries faced with similar social challenges. They are determined to keep working on resolving the issue and extending the impact to society.

***

Background

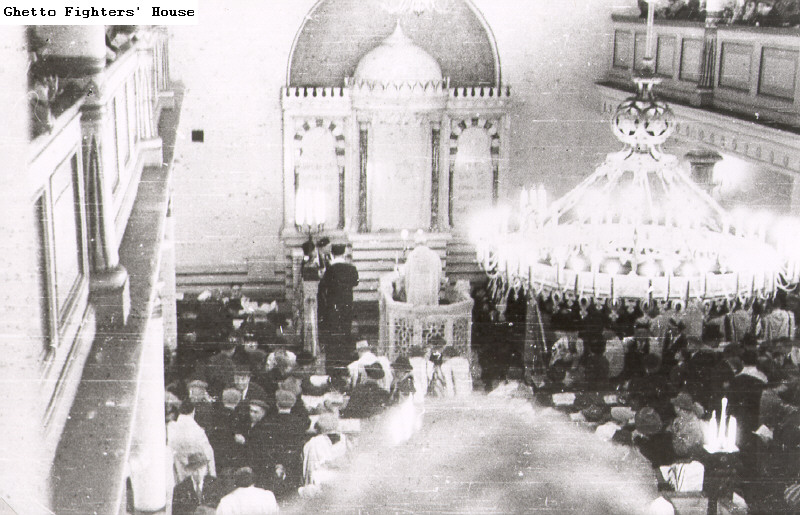

A mother and son of the Roma people, commonly known as Gypsies.

In Hungary, primarily due to their disadvantaged social position, the Roma people are by far the greatest subjects to racism. In public discourse, the “Gypsy” is inseparably bound up with such negative notions as poverty, permanent unemployment, benefits, informal economy, and crime and, more generally, with fears related to existential insecurities. In most social domains, the “Gypsy” is intertwined with a certain inferior class position and social marginality, such as exclusion from or taking the most inferior realms of the formal labor market, with possibilities severely restricted by manifold exclusive processes. The Gypsy-Hungarian ethnic distinction is in many cases a manifestation of class difference, since class positions are heavily ethnicized in many areas of life, in villages and town districts, and in educational and other institutions. While the lower middle and middle classes are associated with majority Hungarians, marginalization from the labor market is associated with the Roma. Everyday social conflicts are hence often experienced as confrontations between different ethnically interpreted class positions, where the “Gypsy” appears as a menace to the middle-class normativity of the majority.

Our team of trainers comprised social scientists whose academic work focuses on social inequalities, public education, and the Roma communities. The project idea arose from a shared urge to engage in activities that have a more direct and palpable impact on the lives of the communities we work with. Therefore, this project was also a way to experiment and to elaborate methods of intervention and ways of committed political engagement that feel right and adequate to us, to our habitus. We held four one-day and four two-day workshops for six groups of university students training to become public-sector professionals and for two groups of Roma university students. Half of the workshops took place in Budapest and the other half in other big cities. In the workshops, participants were invited to work with and reflect on their own social position, their social roles, and their class position. Our workshops are based on the idea that reflection on one’s own social position can help to better understand the behavior of other social groups and encourage collective action and solidarity across groups. Recognizing the social interests and conflicts involved in encounters with the Roma helps to identify the source of negative emotions and reveals how racism veils the real causes of conflicts.

Potential Target Groups and Specific Objectives

The main target group of our workshops is professionals who regularly encounter Roma clients as part of their professional roles. According to the literature, street-level bureaucrats are public-service professionals who represent the state by their work and, on a daily basis, make numerous small decisions in relation to the lives of their clients.[1] Typical examples of such professions are social workers, health care professionals, and the police. In this project, we offered the trainings to university students preparing to enter these professions; in the future, we plan to approach in-service professionals as well.

The workshops address the complexity and tensions of the professional roles related to social assistance, care, and support. We spend time discussing the typical sociological and recruitment characteristics of the professions. We had to bear in mind that university students do not yet have professional casework experience, so the workshops concentrated on their past “private” minority-majority encounters (which most often happened at school) on the one hand and the motivations, desires, and fears related to the caring relationship on the other.

When working with university students, school was often an important theme: we discussed the role of schooling in social mobility, the class-specific strategies related to schooling, as well as the inequalities of the Hungarian education system, and the school’s role in mitigating or reproducing inequalities.

Our other important target group consisted of young intellectuals of Roma background. In these workshops, we discussed the situation of the Roma people within the Hungarian social structure, the typical Roma roles and social phenomena (e.g., ethnically framed poverty, entrepreneurship, and widening middle class), and the constraints of upward mobility. Subsequently, the workshops addressed the tensions of harmonizing the experience of deprived homes and middle-class intellectual roles. By sharing their stories and experiences, the workshops helped young Roma intellectuals recognize the similarities in their backgrounds and challenges and hence share the “weight” of upward mobility.

The Workshops

Melinda Kovai, team members, and other sociologists discussing the contents of the training.

The first part of the workshops concentrated on the social positions of the participants; they shared their memories and their private and work experiences in relation to conflicts with the Roma people. We then explored these encounters in a dramatic form, wherein participants placed themselves in the shoes of both sides and collectively explored the social constraints from which behaviors (stereotypically) associated with the “Gypsy” derive. Ideally, the recognition of common social constraints develops a sense of solidarity and recognition of the differences of the other.

It was important to constantly respond to the social differences among participants and the corresponding differences in career choices. On the final day of the workshops for university students, we set aside time to explore their career choices in the light of their social positions and experiences. While for first-generation young intellectuals our workshops shed light on the constraints and possibilities coming with their upward mobility, for young people coming from long-standing intellectual families the training provided an opportunity to reflect on their privileges.

The following training methods were employed in the workshops:

- warm-up and energizing games

- dramatic exercises, the adaptation of the “wall of success” in particular

- storytelling: sharing experiences, which then become materials for dramatic exercises

- sociodramatic exercises and action methods: the enactment of typical situations related to ethnosocial conflicts, exploring the motivations, positions, and interests of the participants through dramatic enactment

- sharing, reflection, and discussion

The overall aims were that, by the end of the workshops, participants

- understand that society is hierarchically organized along various dimensions and that the distribution of various forms of capital (economic, cultural, and social), based on which class positions form and encounter other social determinants such as housing, gender, and ethnicity, are decisive;

- have a comprehensive idea of the structure of Hungarian society and the perspectives of people in various positions;

- have a reflective understanding of their families’ and their own social positions, their mobility pathways, their career choices, and their interests, needs, demands, beliefs, values, tastes, and so forth;

- understand how society shapes personal beliefs, interests, demands, and tastes and how habitus works;

- understand how social conflicts are sparked by the clash of different habitus and how actors in higher social positions generate such conflicts according to their interests with the aim of preventing the formation of antisystemic alliances; and

- in the light of their own social positions, recognize the opportunities for social action and possible alliances with groups in different but proximate positions to form antisystemic alliances despite the differences in their positions and habitus.

Participants’ Voices

At the end of the workshops, as a closure, we asked all participants to share how they enjoyed the course and which elements they liked and disliked in particular. Two weeks after the workshops, we also invited participants to anonymously fill out a detailed online feedback form. In the questionnaire, they could assess group directing, the structure of the workshop, and the tasks and activities, and they were asked to describe their positive and negative experiences and to give us suggestions for improvement. The majority of the participants gave an overall positive feedback on the training and the trainers. They highlighted that, even though it was an emotionally shocking experience, recognizing their own social position and social differences in general were the most important lesson of the workshop. In the participants’ own words:

“I engaged both intellectually and emotionally—I was deeply touched in both respects. I thought a lot about these themes in the time between the workshops. The workshops were emotionally exhausting, but they were also extremely interesting intellectually.”

“I developed a sense of social remorse. . . . I could do so many things to be more responsible socially. . . . I used to see helpers as being in a great distance from me, as being much more clever, experienced, capable people. . . . Yet they just probably took the initiative, started something, and then became good at it. . . . Next year I will volunteer at a shelter for elderly or mentally disabled people.”

“The topics broke taboos. It is painful to realize how stereotypical our thinking is.”

“I grappled with multiple feelings over a short period of time.”

Based on the feedback and our own experiences, we concluded that it would be more worthwhile to organize two- or even three-day workshops for each group. One-day workshops do not provide sufficient time to process such shattering and difficult experiences. One-day workshops were less successful as participants did not have time to open up or, to the contrary, brought in very moving stories and experiences into the group that could not be processed sufficiently and reassuringly in the given time frame. This difficulty was the most striking in the workshops held for Roma colleges. Furthermore, in the cases of both one- and two-day workshops, participants signaled to us that they would welcome more factual knowledge as well as more emphasis on practical solutions for solving conflict situations.

Citing participants:

“The dramatic enactments were great, but I think it would be good to focus on finding some optimal solutions for these situations. This would have helped us in applying what we learned in “real-life situations.”

“You should give us more factual knowledge on the second day. What is integrated education? How was it implemented and responded to? What is the situation with integrated education now? What are the main political claims about the Roma?”

“I was missing some frontal knowledge, as I was interested in data and practices related to [Roma] educational integration in Hungary.”

Training Material, Dissemination, and Future Plans

Working with Roma schoolboys.

The final output of the project is a detailed set of training materials based on the workshops. The training materials were produced with two objectives in mind. On the one hand, we would like to provide our partners with an introduction to the workshops in advance. On the other, we are planning to disseminate our methodology among university and secondary school teachers who are using action methods or are trained in social sciences. The document explicates why we think that awareness and reflection on one’s own social position can tackle racist attitudes and in what ways our approach is distinctively different from “traditional” anti-discrimination and intercultural awareness raising trainings. We describe the structure and main elements of the workshops in detail.

It perhaps indicates the success of our project that two of our partners, the Faculty of Social Work at Eötvös Loránd University and the Faculty of Psychology at the Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary, integrated our training in their curriculum from 2017–2018 under the title of “Meeting with the Other” as an optional course for social worker students at the former and “Socio-analysis for Psychologists” as a mandatory course for psychology students in the latter’s Intercultural Psychology program. The trainings are led by two trainers: Melinda Kovai, who is a university lecturer at both universities, and another member of our team.

According to the participants’ feedback and our own evaluation, the workshops had the most tangible impact among Roma and non-Roma students enrolled in universities outside the capital. These students predominantly come from working-class families or from families in extreme deprivation. The workshops have the potential to help them not to experience their background as a source of shame but, instead, to recognize the resources in their difficult experiences and thus become professionals deeply and proudly committed to their work with socially deprived children and adults. We plan to orient our future workshops to this target group by developing a longer training in close cooperation with our partner institutions. Furthermore, we would like to begin working with professional adults and adapt the training to their needs.

The training materials are available from the following. (Please note they are written all in Hungarian.)

Training material_Hungarian

[1] Lipsky, Michael. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 1980.